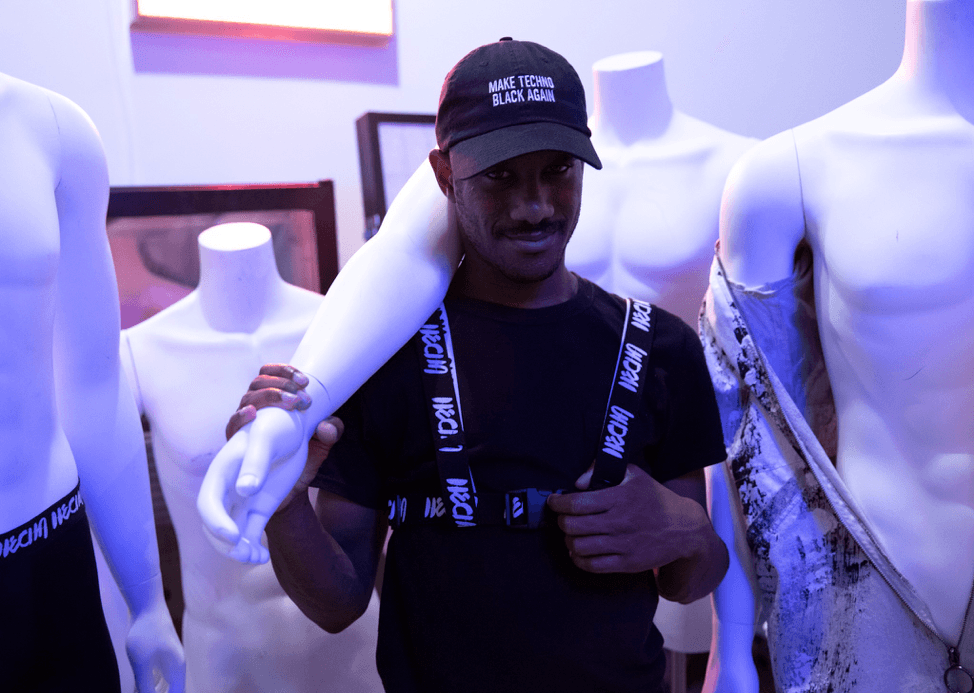

[PREMIERE] Clinical Poetics: An interview with DeForrest Brown, Jr.

Photo by Ting Ding

DeForrest Brown, Jr. is a New York based rhythmanalyst, media theorist, and curator. He produces digital audio and extended media under the name Speaker Music. Threads Radio is proud to present this exclusive premiere of ‘On Bloodthirst and Jungle Fever’—a post-footwork live recording of sonic weaponry towards a cultural ritual of reclamation and revision, featuring philosopher Ariel Valdez and artist Catalina Cavelight.

Alex Honey: Would you like to explain the story behind the Make Techno Black Again project?

DeForrest Brown: It started a few years ago as a meme made by Luz Fernández that had gained a lot of traction, and as HECHA / 做 was forming with Ting Ding. Some of the proceeds from the hats are also donated to an in-school youth music and arts program in Detroit, called Living Arts. I jumped on a year ago as I was getting to know them and partnering with Ting. I felt really invigorated by the idea of it, and also the literal meme-ery of it. It’s a funny, interesting slogan that is somewhat vapid, but is also syllogistically true for a genre of music to be something that must be reclaimed by Black people—it’s just like a syllogistically true statement. I was really interested in that quality of the project when Ting showed me the hat, and I got the idea to compose a mix for it that would act as a soundscape, speculating on the history and culture of Detroit and techno as a form. The thing is, you wear the hat as media, then you download the mix while you’re wearing the hat, and you’re actively engaging with the concept of techno ‘being’ Black. Using documentary clips on Detroit—I start with this recording of a documentary that was actually done by the Ford Foundation about the concept and invention of the automobile, and it states that the Ford industry will never die and cars will be this infinitely growing market, which is obviously ironic because of the collapse of the Ford industry. Being from Birmingham, Alabama—another former industrial center of America—I related heavily to the socio-economic conditions that seem to frame techno, and I’ve always seen the gesture of techno as a direct response to the assembly line worker and Black people having migrated from the declining Deep South up to a supposed White utopia that completely falls apart in the end because of a greed-driven miscalculation between the transition between the second industrial wave of assembly line production culture, and the third industrial wave of digital culture. I wanted to approach the historical materialism of techno by considering the way a lot of the tracks were being etched into vinyl and quickly distributed for immediate usage. With the Speaker Music project I intend to make music for speakers, music that speaks to you… The hat is a particular moment, and the mix encases you in that moment and tries to educate through lived experience.

“Being from Birmingham, Alabama—another former industrial center of America—I related heavily to the socio-economic conditions that seem to frame techno.” |

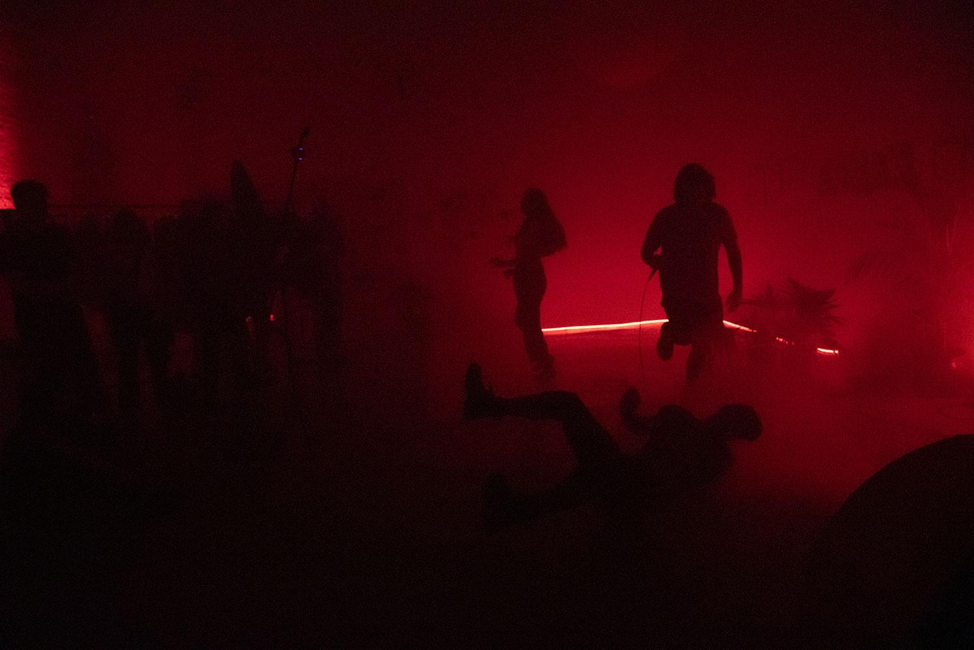

Photo of ‘On Bloodthirst and Jungle Fever’ at HECHA / 做’s Group pop-up at Refuge Arts by Ting Ding

Did you want to speak a little bit about your involvement with the HECHA / 做pop-up event?

Ting was really interested in the institutional art world formats that I have participated in since my moving to New York, and that she had participated in by proxy of rave culture as well as the times at which those groups would end up in the same spaces such as Performance Space or Issue Project Room. I can see a cultural difference but also a clear connection between the rave and well-funded arts spaces. Ting and I talked a lot about what sort of cultural events can happen and draw attention before the late-night rave, and how New York had a format for this in the early 2010’s with spots like 285 Kent, Palisades, Glasslands or Cameo Gallery—these were places where you could see indie and “experimental” acts on the same bill and still go home at a reasonable hour. So yeah, the people that were selected to perform – perrX, naano tani vs baitong.systemes, and Weiss – all represent sections of nightlife that Ting and Luz actively participate in, but they’re just presented in a way that reflects more of their personal engagement with their practice without the demands of pleasing clubbers or the high stakes of an art space. At the end of the night, I presented a new piece called ‘On Blood Thirst and Jungle Fever’ with philosopher Ariel Valdez and artist Catalina Cavelight.

Ting and I were hoping that a sort of cultural sound or notes towards a format could arise from these performances and it absolutely did. We’re all trying to present a cultural sound that lives here, and we just have so many conversations about how to evoke that, and each person performed their own ritual and sort of speculated on their own practices beyond what’s allowable in a club space or a budgeted art space. These people come from amazing backgrounds and actually have cultural ideas that can be played out across sonics. I think we were all just mining ourselves and workshopping in real time just trying to figure out where our culture is and what a multiculturalism looks like in these contexts. Performing as Speaker Music I wanted to participate in using sound as a means of holding an imagined dialogue, and to that end I asked this philosopher to have this conversation with me in real-time while Catalina responded to us with ecstatic movement and living. Ariel spoke to us about the first slave revolt of the Transatlantic slave trade that happened 10 years after the first group of West Africans were taken into captivity, and just the idea of what sort of sounds come from that trauma.

Photo of ‘On Bloodthirst and Jungle Fever’ at HECHA / 做’s Group pop-up at Refuge Arts by Ting Ding

“I think we were all just mining ourselves and workshopping in real time just trying to figure out where our culture is and what a multiculturalism looks like in these contexts.” |

You can listen to the audio version of this interview from [12:50]

A lot of people move to New York for many different reasons. Within that environment, do you think it takes a conscious effort to form communities? Secondly, there’s been a lot of discussion around issues of representation in club culture—do you think that there have been some positive changes happening?

I’d say that one would hope that a sort of cultural music would happen naturally—that scenes would emerge organically from the present demographic. I always joke that people who move to New York are just losers from other places. You think about Andy Warhol—where is he from, Minnesota? He moves to New York, he was not happy where he was from, and he moved to reinvent himself and created the Factory as a means of producing a culture that he could have fun in. That’s the thing, I literally dropped out of college and ran up here one day. I had a bunch of internships that I intended to do, but I moved here because I felt that there was something happening in New York. I felt that there was a real palpability given the way that publications were covering the Williamsburg indie scene. Just after the 2008 housing crash you’d have these people who would come out of liberal arts schools and suddenly be in the Fader, and it really felt like a real on-the-ground journalism was happening at that point to mine the refuge of creative youth excess. And I think that’s where a lot of the arguments of representation comes in. With this mass coverage we started seeing more people of colour being represented, as stuff like GHE20G0TH1K got really popular, but also to the side you had footwork, all of these new sounds kind of emerging—but what that really was, was the first layer of segregation being pulled off of our media representation, for the first time in the history of America. When you think about the fact that the 2000s was like, very indie, and there weren’t that many… Donald Glover has that quote as Childish Gambino where he’s like ‘I was the only Black kid at the Sufjan Stevens concert in 2011’, or something like that. I was exactly that Black person who was at the St. Vincent or Thee Silver Mt. Zion concert in Birmingham, and there were like, 40 people there, and I was the one Black person. I recognised that indie music could touch me as an American music but it was not ‘my’ culture. In fact it wasn’t even the culture of the people I was living amongst, it was more from up here in New York and transplants from the Midwest. I was watching people like Laurel Halo transition from indie pop sounds to this more abstract, free-jazzy techno; and with it, the formats of space in New York started to widen and eventually change into the basic house and after-hours corporatized hard techno sound that more or less defines Brooklyn now.

The issue of representation kind of comes up when you have people like me move to a city like this and actually try and be a part of it. And, ironically, as more coverage came, the content got cheapened. And to answer your question about whether or not things have gotten better, I’d say we’re just seeing a lot of Black people being thrown into the spotlight without any support and then basically hung out to dry. So it looks like something good is happening, but it’s actually just traumatising. You can see that in the way that Yves Tumor performs, you can see that in the way that Mhysa performs. I actually just saw YATTA at The Shed a few hours ago, and that was an interesting moment of seeing this mega venue reach down into our scene and grab someone, and give them a platform. And the space’s capacity wasn’t much larger than Refuge Arts—it was very well produced, but it was arguably the same amount of attention density. As incredible as their performance was, I found that the audience couldn’t quite empathise… There was an empathy gap with what they were trying to present, with their dealing with psychosis and toxic race relations, and trying to tie all these things together with White monolithic thought… but people began to walk out. Most of the room was there, but people did walk out and YATTA would break the fourth wall and be like ‘goodbye!’—and that’s something I’ve actually done with my performances with Kepla is begin to interpolate the room to fight back against the fetishistic consumption and lack of suspension of disbelief that happens in these spaces. So yeah, we’re more present, but it’s become extremely obvious that now we’re here—just people of colour in general—this is not exactly what anybody wanted. And it’s actually created very interested micropolitical lynching situations—I think a lot about Julius Eastman actually, and when he performed a piece of John Cage’s at the University of Buffalo, in which he had a White man and a Black woman and stripped them naked, and stripped himself naked, and performed Cage’s ideas of indeterminacy by empathetically trying to evoke and play with these people and create a symphony of bodies. Cage, who is a gay man, and interestingly as a New Yorker was really staunch about this performance, and didn’t quite get the titillation, didn’t quite get the tactility of this music of the moment. And the next day at this conference at the University of Buffalo he goes on a rant and just blows up about Julius Eastman and humiliates him in front of the entire arts community there and ultimately, in my belief, is the reason Eastman’s whole career derailed, and eventually led to his death. You can’t have a Golden Child like John Cage say negative things about you publicly when you’re Black. I mean, he was the only one who was there… And so anyway, I think we’re seeing a new resurgence of this, of being put on display, and mostly just so that audience and administrators can taste and see if they’re interested in diversity. That unto itself is a traumatic experience that has pushed me into modes of sonic weaponry, and that’s exactly what ‘On Bloodthirst and Jungle Fever’ was—a cultural attack but within ‘civil’ means. And yeah, the HECHA / 做pop-up shop is, I think, Luz and Ting’s way to create a space to work things out in real time and to consider what a scene would look like. Like, this is not a utopian thing by any means, but this istheoretical commune from a mass propagandized media sphere, and there’s a sound for this countercultural commons.

Stay tuned to Speaker Music via Instagram or Twitter.

Author: Alex Honey is a researcher and producer based in Brooklyn, NY. He is the host of Consciousness Raising™ on Threads, and has performed under the aliases DJ Ketosis and classtraitor. His dissertation was written on the emergence of early electronic music in postwar Japan, Europe, and the United States.

Instagram: @classtraitor

Soundcloud:@djketosis

Back to home.