Cedrik Fermont: Syrphe, Life in Noise, and Sociocultural Explorations of the Avant-Garde Climate

For this third edition of her Biodegradable Soundsystem editorial series, Eleanor Bickers caught up with the trailblazing noise and industrial curator

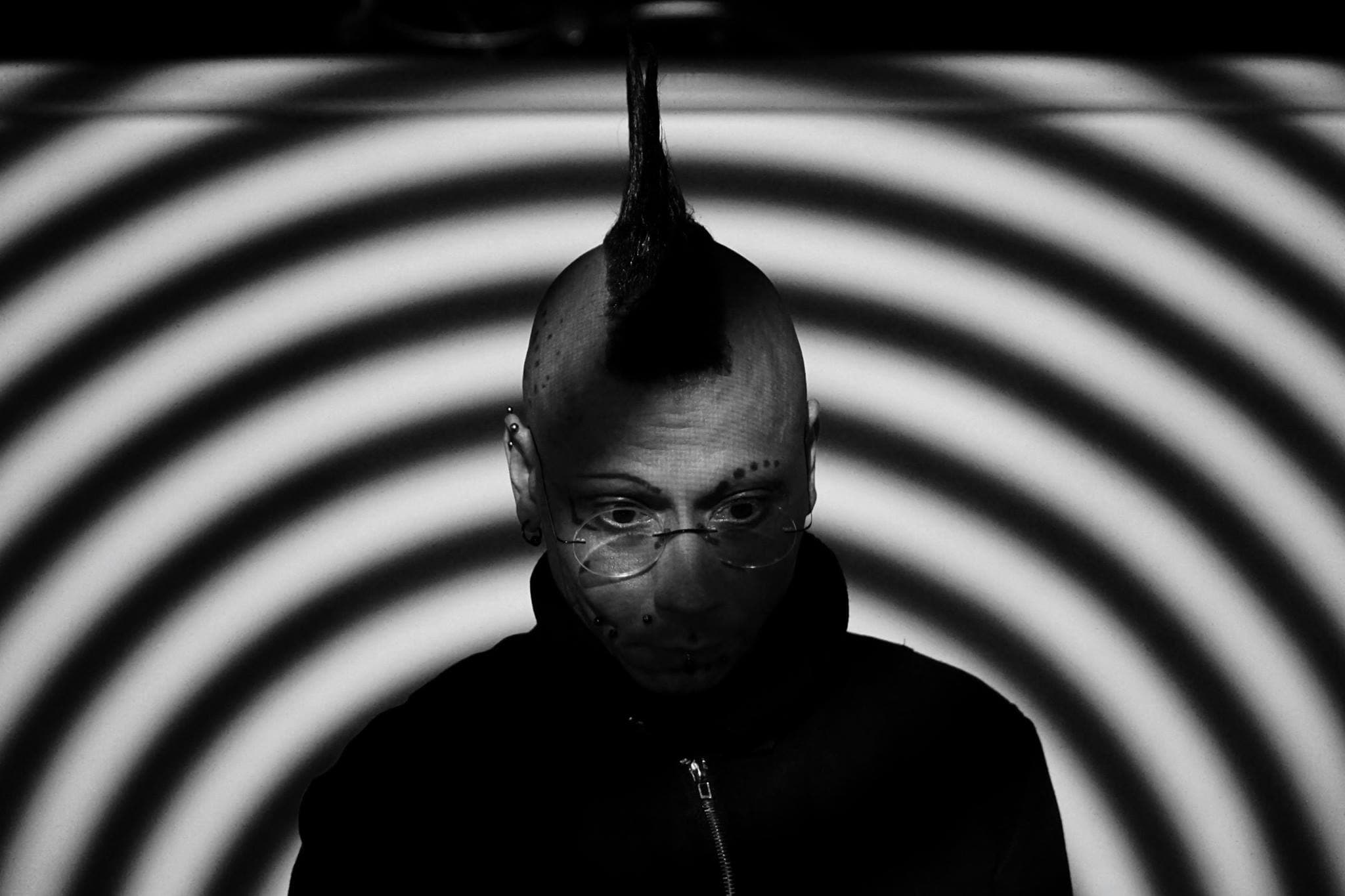

C-drík in Kortrijk, Belgium. Photograph taken by Stephan Vercaemer.

Cedrik Fermont is a multifaceted artist of Belgian, Greek and Congolese heritage who now resides in Germany, navigating the world of improvised industrial, noise and electroacoustics. His plethoric skill set as a musician, composer, DJ, author, radio host, promoter and label manager is holistically bound by the practice of performance and knowledge exchange. Having studied orchestral percussion and drums in the 80s and electroacoustic music at the Royal Conservatory of Mons in Belgium in the 90s, Fermont approaches his work with an academic nucleus – despite having no university education – transcending one-dimensional transmission from an ethnographical and computational study of traditional and contemporary sound. His work is captured by his alias C-drík as well as other personal projects like Kirdec and groups Tetra Plok, Črno Klank and Axiome to name a few. As well as being a musician, Fermont co-wrote the book Not Your World Music: Noise In South East Asia with Dimitri della Faille, which won the Golden Nica award in the ‘Digital Musics and Sound Art’ category of the 2017 Prix Ars Electronica. The scholarly and practitioner-led book provides an alternative perspective of noise, dismantling sexism and colonialism at the genre’s core and exploring its explicit rooting in social and political interaction.

In this Q&A session, I explored Fermont’s label project Syrphe: a cross-cultural documentation of the African and Asian diaspora, examining the interpretation of the aural and socio-political ideology of noise. The potent tension that Fermont induces alongside his hand-picked label contributors is a direct result of his relationship with mobility, having spent prolonged periods of time researching the sonic tide of urban and rural landscapes within these continents.

~~~

Eleanor Bickers: What was the motivation behind starting Syrphe, a project devoted to sound mapping cultural corners of the globe, particularly the African and Asian diaspora?

Cedrik Fermont: That is a long story…

At the very beginning, I wanted to put out my first solo CD and publish some of my other projects. But following the lack of representation of artists from most Asian countries and Africa, I decided to also focus on this, especially from the moment I started to play outside of the secure European and North American world: Istanbul in 2003, Bangkok in 2004 and a six months tour in China, South Korea, Vietnam, Laos, Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia in 2005 that literally opened my eyes and encouraged me to publish and promote electronic and experimental music from Asia and Africa that so many people seemed to ignore.

One of the main origins of this motivation could be seen as a frustration I presume.

When I was a teenager and young adult, in Belgium, I often asked myself why I was one of the very few ‘brown’ persons in the punk, goth, industrial, experimental, EBM, noise scenes and it quickly pushed me to try to find out what was happening in non-western European and North American countries. Back then, in the 1980s and early 1990s, even accessing alternative music from eastern Europe, apart of a few Yugoslav, Soviet, Polish or Czechoslovak artists, was not an easy task, so no need to tell how difficult it was to find music from far away places, even from Australia or New Zealand.

I started my first tape label (Sépulkales Katakombes) in 1991 and published several international compilations that I wanted to really be international. For many people, international often meant Europe, North America, Japan and Australia, which sounded too limited to me.

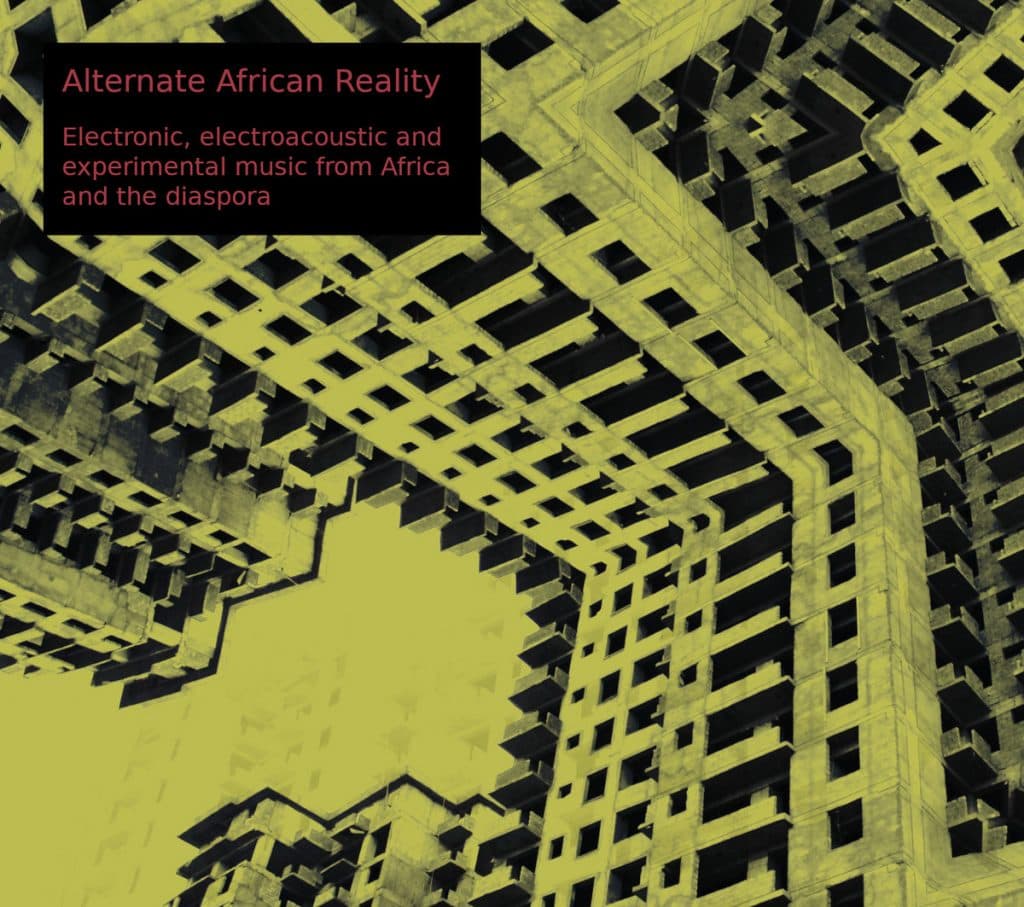

Back then, the task wasn’t easy, especially due to the fact that we didn’t have internet but in the end I managed to publish five of those compilations and the last one published in 1996 included 25 artists from 25 countries: Eastern and Western Europe, Australia, Brazil, Chile, South Africa, Japan, Canada and the USA. So, the compilations that I published on Syrphe from Beyond Ignorance and Borders in 2007 to Alternate African Reality in 2020 and those in between are a continuance of what I did in the 1990s already but with better tools (internet, easier possibilities to travel), better connections and better financial opportunities.

[You can find a digitised version of the tape here]

Photograph taken by Andrea Kriszai (2011).

EB: How did your musical, ideological and cultural experiences help to form the Syrphe label?

CF: My musical experience and tastes have become wider and wider with the time, especially since I used to work in a media library in Belgium where we had a collection of thousands of CDs and vinyls. This huge amount of music, even if not comparable to today’s digital world where hundreds of million of releases are instantly accessible, allowed me to train my ears to understand music that I didn’t know or didn’t know so well and helped me to see what was published, how, where, from where and why and that is partly responsible of my way of working and researching now.

Also, touring several months per year, trying to meet as many musicians and artists as possible and performing in countries where very few people wanted to go for various reasons provided me a good reason to, at least until now, mostly focus on Asia and Africa, even though there could be other interesting places to document as well.

I’m a stubborn person and from the 1990s until the 2010s, I’ve heard too many people, even friends, telling me I would never find electronic or experimental musicians in, say, Myanmar, Kosovo, Indonesia, Iraq or elsewhere. And the more they’d tell me that, the more I wished I could go to explore those places and find out by myself. And I did it. My belief is to not believe what smarty pants tell me and to not follow the masses. I want to see the real world with my eyes and not through a screen or people’s misconceptions of regions they never explored. Therefore, Syrphe is, hopefully, providing a more honest view of the world as many people don’t know it.

I also believe in decolonisation of the arts and culture in general (and I don’t only speak about the results of western colonisation) and am a strong supporter of networks and cultural exchanges in all directions, and as much as possible, to refer to Deleuze and Guattari, rhizomatic networks and collaborations, we all have to learn from each other, even when some may have a greater knowledge in a certain domain than others; treating the other person as an equal, providing the other person the same opportunities than any western artist would be able to access, no matter what their genre, philosophical and cultural background are.

My experiences taught me that many musicians and composers outside of the Euro-North-American-Australian scenes are well aware of what happens here and may have a great knowledge in history of electronic and experimental music and western history in general while the other way round is often not true.

Speak about John Cage, Merzbow, Einstürzende Neubauten, Pierre Schaeffer with some composers in Kenya, Syria or South Korea and they’ll tell you they know about them but if I mention Slamet Abdul Sjukur, Dariush Dolat-Shahi, June Schneider, Yan Jun, Seok Hee Kang, Juan Blanco to name a few ‘big’ ones, how many non-natives, will tell they know those composers?

But this is not the only issue, if I speak about Eastern European pioneers: Włodzimierz Kotoński, Nokolai Voinov, Boguslaw Schaeffer, Mitar Subotić, who in the UK, China, Canada, Argentina or Morocco will tell me: ‘Hey, sure, I know everything about their compositions!’ ? Very few names from eastern Europe will pop up: Sofia Gubaidulina, György Ligeti, etc. Synthetic and electronic music were born in the USSR but few people seem to be aware of it.

This is partly due to the colonialist past but also the way music is shared and travels and music history is taught, wrongly taught. I just hope that Syrphe may open some ears and eyes and other labels that have a special focus too, such as Noise À Noise in Tehran that publishes a lot of electronica, ambient and electroacoustic music, especially from Iran, Zabte Sote, also dedicated to Iranian electronic and experimental music, Ruptured that publishes a lot of artists from Lebanon and hosts a radio show, Ujikaji in Singapore that publishes artists from the region, Nyege Nyege Tapes and Hakuna Kulala that focus on electronic music from east Africa and beyond…

EB: You performed in industrial and electro duos like Axiome and Tetra Plok amongst many others, as well as your solo moniker C-drík. Who were your greatest influences in your early days of production and performance?

CF: In the early days, I don’t think I and we (with Axiome or some other projects like Črno Klank) had direct influences as we didn’t have a lot of instruments or effects and very little experience in the late 1980s and early 1990s so we were trying to do our best with what we had. I think that we were experimenting a lot but the results were sometimes clumsy or amateurish.

Then, if we speak about Tetra Plok that was born in 2003, it’s an all different story. I don’t think we thought to compose music like one band in particular but we had a clear idea in mind: recording music in the field of minimal wave, electro and perhaps EBM, I guess artists like Chris & Cosey, Drexciya, D.A.F., Liaisons Dangereuses, and many more, may have indirectly shaped a bit of our music.

Regarding my solo projects, my main influences were and still are all what I listen to, such as nature, music, sounds of urban environment or construction sites, sounds of every day’s life as well as my mood, state of mind, politics, emotions, life in general, so to speak. I’m not directly influenced by one artist in particular, until now.

Tasjiil Moujahed (Jawad Nawfal and Cedrik Fermont) live in Beirut. Photograph taken by Tanya Traboulsi.

EB: Your music blends a scientific and literary approach to sound design. How far do your influences stretch when it comes to approaching experimentation in electroacoustics and industrial?

CF: There’s no limit. I try to document myself about recording techniques, sound technique and composition, not only from academic sources and just experiment. In normal time, I attend several concerts per day, if not every day when I can, and a lot of free improvisation and experimental music. I enjoy attending concerts, close my eyes and dive into the sonic world but I also often look at the musicians and analyse their way of performing or the self-made instruments they might use in order to get some new ideas.

I also listen to a lot of electroacoustic music and try to understand the way one piece or another has been composed, not to copy it but to, again, get new ideas and experiment with techniques I didn’t think about.

EB: Your recent Syrphe release The act of refraining from speaking seems to prioritise acoustic design over complex software editing. Has this always been at the forefront of your workflow? What methods do you use that bring out the best of your electroacoustic and field recordings?

CF: Even if most of my work is electronic, acoustic sounds have almost always been present in my compositions, either played live or sampled and often modified. But this time I wanted the acoustics to be the centre of the piece and not the electronics and a forthcoming CD contains compositions that sound even more acoustic than those pieces.

About the methods: it’s often a trial and error way of composing. I rarely have a clear idea in mind, I never put any predefined composition’s structure on paper. I may have ideas that I try to explore but sometimes it’s just random. I hear sounds I recorded or an object or instrument I used to create sounds and start to assemble parts that seem to work together and create a narrative, if I don’t like it, I modify it.

The way I compose is similar to the way I live. I don’t like routine and don’t always enjoy structured and normative ways of living.

EB: For the 2020 compilation Alternate African Reality…, you mentioned that travelling globally to perform as an artist allowed you to meet lots of inspiring African artists. How valuable are those experiences to you?

CF: These experiences are priceless. Wherever I travel is always an important step in my quest to discover other cultures, languages, social structures, communities, art practices, and other forms of vegan food, ah ah. To me, even if the main centre is music, the cultural exchange, hopefully, helps me to understand the world a bit better. You can read books, as important as it is to read good books, or watch or listen to well made documentaries they will never provide you the same experience than being there with an artist that will talk to you about their music, family, politics, social issues, the terrible traffic in the capital and introduce you to their friends and explain you how to prepare the beans freshly collected from the garden, sipping a hot orange tea while observing the neighbour building an experimental instrument, and then you go and meet that noise artist’s mother, happy to meet and feed that foreigner who travelled from afar to meet her daughter or son because of a music connection. And then you swap music, magazines, you talk about projects, you collaborate, maybe. What else could beat that?

Various Artists Alternate African Reality – Electronic, electroacoustic and experimental music from Africa and the diaspora (Syrphe, 2020).

EB: How have you been coping artistically in a time where movement is limited – is travelling usually an important aspect of your work?

CF: Yes, travelling is a big part of my work, as I tour up to six months per year to perform, give talks, workshops, explore and document but also because I’m always eager to learn about cultures, regions, countries, languages I don’t know or don’t know so well.

So, all of a sudden I got caught in the middle of a tour and life completely changed.

It was at the beginning a bit stressful as I feared to be stuck in Eswatini and then South Africa but fortunately came back on time to Germany, wondering how my financial situation would become.

In the end it’s not bad at all: on one hand being in Berlin during this crisis has been a privilege as many artists have received some help; that in most cases doesn’t cover or the loss but in my case I have got many opportunities to do online (and sometimes on air) projects, such as radio shows, discussion panels and now, step by step some concerts on site with limited audience.

This crisis allowed me to work on albums and collaborations that were sometimes set aside for several years and I now have more time to read, think and write articles which is also positive, as well as cycling. I often cycle alone, especially outside of Berlin’s main centres: in industrial zones and nature, especially in Brandenburg. I take some pictures, record sounds, think about what I could do with this material and sometimes come back to grab more sounds or a composition or collect metal junk to create new sounds. It’s another way of travelling and exploring and I’m happy with it too.

EB: What is the importance of your projectal palettes being geographically widespread, would you say this project is an education tool for the western world?

CF: Not only the western world, on one hand I think we all need to learn from each other, on the other hand, it is to me obvious that the western world is not the only self-centred world and when we speak about the western world, it never covers all so-called western countries; many Eastern European ones are rarely included in this western notion.

Even neighbours don’t always know about each other.

The first time I went to China, local artists were surprised I had played with noise artists in Vietnam. The first time I went to Singapore, some local artists did not believe there was any experimental music in Indonesia. The first time I went to Egypt, most artists didn’t know what was going on in Sub-Saharan Africa. My friends in Iran were surprised I played in Iraqi Kurdistan, my friends in Iraq were surprised there was a big scene in Iran…

EB: You co-wrote the book Not Your World Music: Noise in South East Asia with Dimitri della Faille, which won the Golden Nica award in the ‘Digital Musics and Sound Art’ category of the 2017 Prix Ars Electronica. Where did the desire come from to develop your research beyond sonic documentation?

CF: It was in my mind for many years but apart from three essays written several years earlier, I was more collecting data than putting that on paper, I always thought that I should gather more information but that was without end.

Dimitri, who is not only an experimental musician but also a sociologist and professor kicked my backside, so to speak. He told me that we both extensively travelled in East and South East Asia and had acquired a lot of knowledge that we should put on paper. He knew I was and am still an obsessed archivist or collector depending on how you see this and that we should finally make this first publication, because, alone, I would possibly never finish to write because I can never stop collecting information, write notes and think I need to find out more. Documenting South East Asia was to us important as the scenes there are very interesting, sometimes at an early stage sometimes not at all but those artists, labels, etc. had to be included on the international map too.

It was a bit challenging of course as being the first ones to document such a vast region would trigger a tiny bit of animosity or jealousy, especially due to the fact that we are not from there. But to us it was essential and we hoped some other local artists would also document what is going on there and perhaps correct some of the mistakes and approximations we may have done or lack of information about this or that person for example. We knew from scratch that this book would not be perfect, that is impossible but those imperfections would possibly encourage some other authors to write and document too. It was a first step, someone had to do it, whether it is us or South East Asians is to me not that important, the goal was to document and trigger something and it seems it worked.Since then, Indra menus and Sean Stellfox both based in Java have written and published Jogja Noise Bombing: From the Street to the Stage for example. It’s a valuable documentation and more will come.

Fermont at Prix Ars Electronica (2017). Photograph taken by Florian Voggender.

EB: Your Syrphe catalogue decentralises westernism in electronic and avant-garde music. Is there an importance to break down these barriers in 2020 given that we are beginning to enter a more politically aware climate?

CF: To me it is still crucial. Yes, more people, journalists, magazines, event organisers seem to wake up and realise that there are many artists in the field of contemporary, electronic, experimental, free improvisation, punk, metal or else in Latin America, Africa and Asia but we are only at the dawn of this recognition and I’m afraid that in some cases this is closer to exoticism than full recognition. I still too often hear people either being surprised that artists in Angola, Uruguay, Iraq or Myanmar are also active in the field of experimental and electronic music or modern art in general and I also hear those who still split the world in two: ‘us’ versus ‘them’ and ‘them’ often equal weirdness, exception, abnormally, exoticism, rather than equality.

We see the same patterns occurring with the gender issues, the representation, lack of representation or lack of recognition of women or other genders in certain scenes tends to make some believe that a women who does death metal in Iran or is a party organiser and DJ in Kazakhstan is weird and I believe it’s a wrong way of seeing things. It’s not odd, it is in some cases exceptional, maybe, but not strange.

I wish we could live in a world where I would not feel the need to add people’s nationality or gender next to their names when I publish their music or organise a concert but unfortunately, we don’t live in an ideal world (yet): on one hand I want to make a statement and demonstrate that not only westerners do this music and on the other hand due to the current climate, I need to prove to some that I promote diversity (even though I have done it since the 1990s).

I don’t use the verb ‘demonstrate’ by accident, I suppose that most people don’t think about the root of this word: ‘monstrum’ in Latin that lead to ‘monster’ in English (from ‘monstre’ in French), the monster is the other, the stranger, the one who is out of ordinary. We need to ‘de-colonise’ and ‘de-monstrate’.

But this ‘unusual’ being is not unusual for some westerners only of course. If you go to China and speak about an experimental music composer from Sri Lanka, or Uganda, they will probably be surprised or doubtful, and if you tell an Egyptian than you know somebody who does live coding in Mauritania, you might face a similar reaction. This is why I think I have to keep this focus but also that we need more networks, more exchanges, more collaborations, hence, even though Syrphe as a platform and label mostly focuses onto Asia and Africa and bit Latin America, it is also promoting cross-collaborations, I do not wish to create a ghetto or a zoo to expose ‘exotic sounds from remote places’.

EB: Would you say that global music and non-western musicians are given enough of a platform in the electronic music space? Are there any other platforms, labels or promoters championing this platform, perhaps in both a non-western and western context?

CF: For several years, I see that there is a growing awareness and interest in the non-western scenes, some labels started a while ago, sometimes occasionally, some others do it in a way I sometimes find suspicious, either following a trend or feeding their own ego while doing nothing else than putting out releases without making any efforts to promote the artists or remunerate them when possible.

I think that we should not only count on western platforms anyway. There are many non-western platforms that work on promoting their communities, that is very important. I think of Mujeres que experimentan con sonido – Latinoamérica (Women experimenting with sound – Latin America), a list of female composers freely available online that anyone can update, Iranian Female Composers Association that includes Iranian composers from Iran and the diaspora, Asian Music Network which connects experimental musicians and improvisers from Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, etc., Experimental Electronic Music Scene of Iran – EEMSI, Mideast Tunes, founded in Bahrain, that provide a space for artists from the region where they can upload some music, their biography and contacts, Unite Asia that focuses on metal, punk, hardcore from around Asia but is pretty open to some other genres too like post-punk, goth or noise, Chinabot, another important label and platform that promotes artists from South, South East and East Asia, Latinoise, that focuses on Latin American noise and experimental music, Latin American Electroacoustic Music hosted by La Fondation Daniel Langlois, Mkito, a platform that could be compared a tiny bit to Mideast Tunes but with a more mainstream and pop music focus onto east African music, Jokkoo, based in Spain but dealing with electronic, hip hop, experimental and “contemporary” music from Africa and the diaspora, Nyege Nyege tapes and Hakuna Kulala, that are not purely based in Uganda but promote a lot East African electronic music among other things and manage to invite artists not only from the continent but also Indonesia, China, the USA, Belgium, etc. There was Network 77 in Cape Town during the late 1980s until the mid-1990s that promoted and published South African music, especially electronic and ambient but also some rock oriented artists too. The list could go on and on, it’s not new and little informal, but nonetheless an extremely vivid network to mention is Indonesia itself where artists, labels, publishers, cultural centres, academic or DIY are incredibly well connected and often supportive towards each others and the foreign artists who come on tour, it’s also a multimedia and multi-musical network that can include harsh noise, electroacoustic, chiptune, grindcore, punk, hip hop or folk music, music is spread through platforms such as Archive and Bandcamp mostly as well as cassettes, CDs and often CDr’s or vinyls.

Photograph taken by Frank Sebastian Hansen (2016).

If you dig the past, you can find interesting projects like the compilation Periférico: Sounds From Beyond The Bubble published by Sonic Arts Network in 2007 which includes artists from Iran, Angola, Lebanon, Palestine, Ukraine, Egypt, and so on. Or in the more academic world, musique concrète and electroacoustic composers like İlhan Mimaroǧlu, Bülent Arel, Halim El-Dabh, Mireille Chamass-Kyrou, Toshiro Mayuzumi, Makoto Moroi, Luo Jing Jing, to name a few, have got their music released on various compilations throughout the 1950s till the 1980s.

And then you have other platforms or magazines such as Norient from Switzerland, the magazines/blogs Okayafrica, Djolo, Digitale Afrique, and so many more! And festivals like CTM in Berlin, the Darmstädter Ferienkurse in Darmstadt that are opening their programme more and more to non-westerner composers and students as well as Donaueschingen Festival, all in Germany as you can see. Geigermusik in Gothenburg is also working on a more inclusive programme, Irtijal in Beirut invites a lot of artists from the region but also from around the world, Jogja Noise Bombing in Yogyakarta, a big international noise gathering; platforms and institutions like DAAD and Goethe Institut in Germany, L’Institut Français in France, the British Council, the Japan Foundation, all of them contribute in a way or another to develop some networks and connections, in some cases, it’s also some sort of soft diplomacy, I don’t want to pretend that all is smooth and perfect.

EB: You mentioned artists like Slikbak from the SVBKLT crew in your monthly music breakdown on your blog. Which artists and/or labels are pushing a forward thinking sound at the moment that you are enjoying?

CF: I can list a few labels to give a more global answer, it’s a personal list and not an absolute top of the top and it also reflects a lot of what I am currently listening too or following at least, in some cases, not all the music published there is what I enjoy but the topic and contexts have an interesting value. Regarding the artists, there are so many that it is difficult for me to give an objective answer. I follow hundreds of artists and labels on Bandcamp or on their websites and still buy plenty of music from the past too, old or new I mostly buy physical releases.

I can name a very few, from Cindytalk, Eartaker, B L A C K I E, MC Yallah, Puce Mary, Fahmi Mursyid, Marja Ahti, Francisco López, Sukitoa o Namau, Senyawa, Moor Mother, Elvin Brandhi, Koenraad Ecker, Vinyl -terror & -horror, Dhangsha and his numerous current collaborations, I’d better stop here, sorry for those I didn’t mention, there are too many!

Label: Noise À Noise, Zabte Sote, Nyege Nyege Tapes and its sub-label Hakuna Kulala, Crónica, Discrepant, Ruptured, Plus Timbre, Sub Jam, Social Isolation, Chinabot, Kandala Records, WV Sorcerer Productions, Sono Space, but also Mechatronica, possibly not so forward thinking but I’m addicted to electro and many of their vinyls are simply great, and many more…

Listen to the third episode of Biodegradable Soundsystem via Mixcloud here:

Author

Eleanor Bickers is an electronic music enthusiast and writer based in London. She runs the Biodegradable Soundsystem series on Threads Radio, exploring the symbiosis of written, verbal, and sonic communication. In her spare time she often finds herself DJing, raving, and imagining alternate realities. You can find her on Instagram: @lnr_dj

Back to home.