Definition Hardcore: Channelling Nineties Discourse

Following last month’s German trance feature, Biodegradable Soundsystem’s second edition sees Eleanor Bickers map the shifting tides of digital hardcore.

Molly Macindoe, A New Year’s Eve, Mill Mead Road, Tottenham Hale, London (1997) Photograph © Molly Macindoe, 1997. Image courtesy of Saatchi Gallery, London

Hardcore, by definition, performs as a skeletal affirmation of media. Associating a method of communication with a brutal and violent, yet sincere and engaging message, it cultivates a community of creators and consumers who coexist as an escape mechanism that artistically dismantles and challenges patriarchal messages. What is often used to accessorise diverse forms of media became a belief system intertwined with diehard music subcultures, providing a radical sense of relief. Original hardcore stemmed from the industrial and punk age of the 70s and 80s, whose attitudes influenced the rhetoric it propelled in its musical, performative, and communal apparatus. Naturally, with the burgeoning DIY culture of the ’90s, it was only a matter of time before hardcore spawned in the electronic music climate, catalysed by the pioneering sound of Chicago house and Detroit techno.

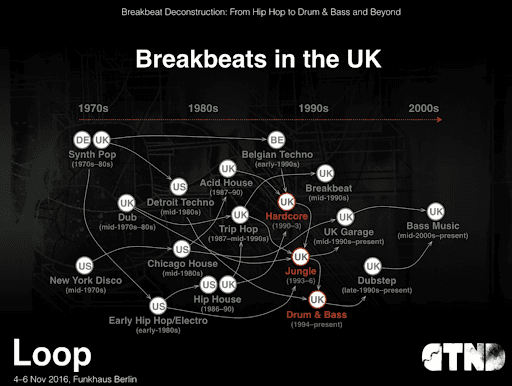

This uprising, once an offshore visitor now a native stalwart, developed within the ‘golden years’ of electronic music (1988-1994) and whilst there is a firm understanding of its birthplace in the UK, there is a lack of clarity in its characterisation. The funk and jazz sampled breaks of hip hop like the Amen break and Funky Drummer that unravelled into UK pioneers of jungle, coexisted with the 4×4 rave and techno inspired hardcore of Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands. Using Dr Jason Hockman’s deconstruction of breakbeats, we can identify hardcore’s lineage as hip house, acid house and Belgian techno, which traces the early influences to the Low Countries (Western Europe) and the Midwest (USA). This doesn’t consider the outer breakbeat possibilities like industrial and EBM that lent their aural makeup to hardcore techno and gabber, although it’s worth wondering if the definition of these styles used the term as the aforementioned skeletal affirmation, hijacking cultural production by reformatting the record.

Whilst the vintage research of ‘ardkore philosopher Simon Reynolds echo the contemporary composition of Albuerto Guerrini’s (aka Gabber Eleganza) Never Sleep archives, you can still trace the vein of this ’90s hedonist carcass, plucked away by authority and developing neoliberalism, remaining a misinformed era of dance music history. This feature will explore the undulating narrative that hardcore electronic music exposes, drawing on its influences and sub categorical strands that birthed breakbeat and jungle, darkcore, hardcore techno, gabber, hard trance, acidcore and terror/frenchcore. This will be discussed through two perspectives, inviting Oskar Jeff, bass music fanatic and writer for Loud & Quiet magazine to render provocation and provide an alternate stance on the definition of hardcore.

Dr Jason Hockman: Breakbeat Deconstruction: From Hip Hop to Drum & Bass and Beyond – Loop summit 2016

Part 1 – Early Influences and Proto Palettes

We Have Arrived: The Journey of Planet Core Productions

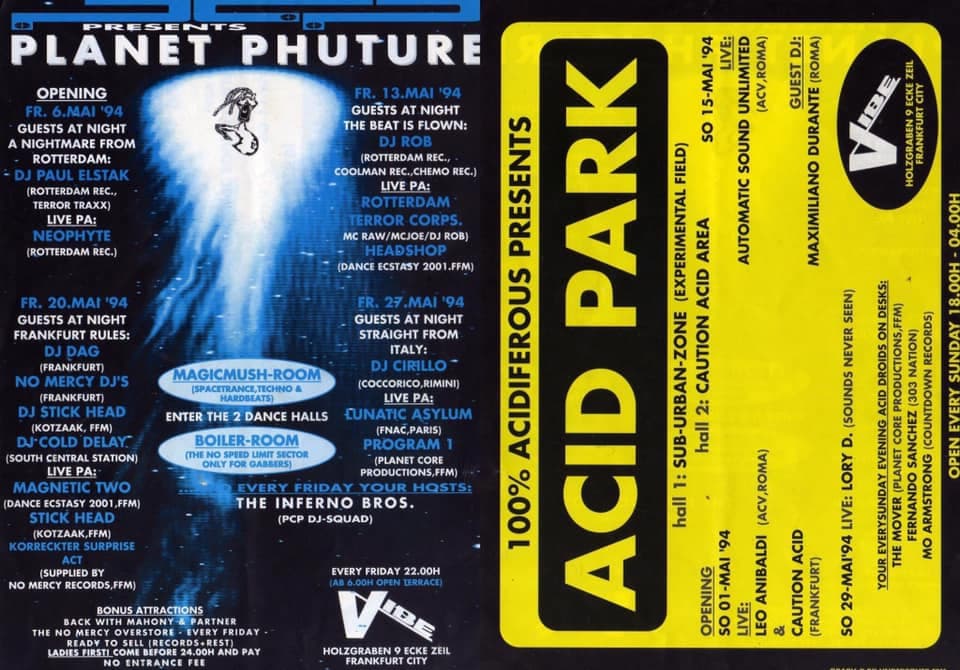

In hardcore’s infancy, there were significant distinctions arising across three countries in Europe that drew influence from one another to become confluent in style and message. Whilst Bronx break samples, Chicago house and Jaimaican dub influenced Yorkshire bleep were formulating acid house in the UK, Marc Trauner founded Planet Core Productions in ‘89, a techno label from Frankfurt which has made a name for itself in being the first hardcore techno catalogue to exist. In a 2019 interview with RedBull Music Academy, Trauner spoke about his early involvement with electronic music. “I really liked the sound of Detroit … but it was not hard enough for me. In the beginning we mixed up hip hop with techno sounds and played in [hip hop] battles. They thought we were totally mad because we didn’t fit in, then one day I looked in the mirror and thought ‘I’m white, and I’m not coming from Compton so we need our own street music in Frankfurt’ – and that’s how hardcore techno was born”. The undenying influence of hip hop caused a seismic shift in the interpretation of dance music in Germany, reckoning with unorthodox sonic sadism as their form of radical relief.

Acardipane released the EP Reflections in 2017 in 1990 under the alias Mescalinum United, including the first 4×4 hardcore techno sound to arrive with the track “We Have Arrived”, of which its 1992 remixes have since been remastered this year on Planet Phuture to mark 20 years of hardcore techno’s legacy. “We Have Arrived” stampeded the club circuit with its innovative distortion like neurochemical warfare so much so that the sound engineer from club Music Hall in Frankfurt thought Acardipane had destroyed his PA. With a primitive sound in place, he inspired artists like New York techno legend Joey Beltram, who pioneered the hoover synth noise with the track “Mentasm” under his alias Second Phase, produced on the Roland Alpha Juno 2. This track introduced a sound to the techno space that was alienated, and inspired Acardipane to propel the hardcore infrasonic into palpitating, menacing and dystopian parallels. Splintered throughout his countless alter-egos, hardcore techno became Acardipane’s signature style. In Simon Reynolds’ Energy Flash blog, Acardipane spoke of his most personal moniker, ‘The Mover’ – “We want to carve our initials into the body that is history. So that in 20 years people go ‘Hardcore techno – that was PCP!’, like punk was the Sex Pistols and rock was the Rolling Stones”. His rock n’ roll approach to electronic music has contributed to the history books of ‘phuture’ techno.

PCP Planet Phuture 1994 Flyer – Marc Acardipane Facebook

The Original Sound: British Bleep and Bass

By ‘91 hardcore had established a number of proto sound palettes as its undetermined identity. But the diaeresis of bleep techno synthesis and Belgian techno served as early influences for their weighty sounds.

Bleep techno is the messiah of the UKs dance music lineage. The publicised 2019 research from Matt Annis is pertinent to the education of UK bass and where we can attribute our subcultural heritage. For no better words, we would be nowhere without the influence of Jaimaican migrants to the north east area of the UK, notably Yorkshire, where dub music and sound system culture enacted as the template behind the mechanics of the low frequency and soulful aural compound of bleep and bass. Robert Gordon, the inaugural producer of Warp Records, was a crucial figurehead in channelling dub into a novel genre known for its “3-D spatial design” (Matt Anniss for Resident Advisor, 2014). Without bleep techno, and without Warp Records, it is difficult to decipher how British dance music would have developed into the microcosmic counter-cultural phenomenon that has been so widely documented in the DIY stratosphere. The mechanics of bleep used the influence of dub, Detroit techno and Chicago house and repurposed the sound for British warehouse raves, lending to a palindromic palette that would never be defected. There was an inherent need from post-industrialisation to aggregate a grassroots creative movement, mutually sympathised by a structurally neglected working class force against the futuristic possibilities of technology and movement. The history lent itself to the uprising of acid house raves across the country, enacting spaces for UK hardcore to develop. Whilst the parties remained local, the sound transcended borders; even Richie Hawtin was influenced by the bleep sound, heard in his 1990 release “Technarchy” under the ‘Cybersonik’ moniker.

Belgian Techno: The ‘Nu’ New Beat

The harmonic aural artefacts of bleep techno shared a similar fate with Belgian techno. In fact, the sound of Belgium has taken a backseat in its documentation and has been “far more innovative than people give it credit for” (Bill Brewster for Last Night a DJ Saved My Life, 1999), referring to its previously misunderstood new beat heritage. What served as an intersection between German EBM and Chicago house grew from Popcorn, Antwerp’s answer to northern soul, replacing amphetamines with mountains of Tuborg. But during the Cold War, with Russia’s missiles pointing at Belgium, their sound became rebellious, adversely to the robotic sound of Kratfwerk’s EBM sound in Germany. It was the politically driven conditions that provided the punkness of Belgium’s hardcore style, avant-garde turned harshly exposed, from wrong speed new beat amplifying bass frequencies, to be warped up to low octane catastrophic gradients, like “Quadrophonia”. At this point everything was possible. “The people here had a lot more experience making and listening to electronic music, so they were primed to produce it … producers here already understood electronic music and how to make it” (The Sound of Belgium, 2012). This knowledge led to the introduction of daring and aggressive sounds. “Coming from rock I grew up listening to Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath, so this was the dance music equivalent of that” mentioned Joey Beltram. Belgian techno lifted out the British breaks that birthed the acid house movement, showing the geographic musical exchange that allowed hardcore to be interpreted and recontextualised. In return, Belgium characterised the dark stabby riffs that formed the basis of a hardcore synth melody: listen to T99’s “Anasthasia”. The toughness of the music coincided with the country’s laissez-faire approach to club curfews. “People slept on Wednesday. You had the club, the after-club, the after-after club, then the club again … only in Belgium”. Born out of this climate were iconic dance labels like R&S and Bonzai who embodied the spirit of rave. “I wanted to shock people, make sure it doesn’t sound like anything else” mentioned Renaat Vandepapeliere, founder of R&S, who released records like Joey Beltram’s “Energy Flash” as well as “Mentasm” with Edmundo Perez as the duo ‘Second Phase’. Naturally, Belgium met the same fate as the UK, whose lawless curfew and movement rules were met with authoritarian exploitation.

~~~

Part 2 – UK Hardcore: A Breakbeat Deconstruction

by Oskar Jeff

Encompassing a dizzying array of international scenes and time periods, some hardcore styles mutated from each other while others seemingly appeared in parallel. The fundamental characteristic across these styles seems to be an intensifying of a previous model; taking sounds and pushing them to breaking point, both technologically and socially. Factions of both the artists and audience tire of the status quo and look to reconfiguring the sounds toward a new – and often harsher – future.

Though hardcore would go on to describe much harder and faster forms of dance music throughout the ’90s, arguably the most creatively anarchic and sonically off-kilter period would have to be the UK’s breakbeat hardcore scene, a hybrid that broadly fused elements of two of the UK’s most cherished US imports of the ’80s: Chicago’s acid house and New York’s hip hop. The tempo was ramped up and the driving force of the breakbeat provided a frantic forward-momentum, somewhere between funky and fucked (a scenario the British audiences were more than eager to visually interpret in dance).

Underdog Crew in Dave’s Bedroom 1994 – Vinyl Fanatiks

Arguably, breakbeat hardcore ushered in the age of the UK D.I.Y dance music scene. As Steve Beckett of Warp Records recalls in Simon Reynolds’ seminal Energy Flash: “Dance music was all imports, then people in Britain started doing it for themselves”. Though there was certainly British producers working prior to the evolution of breakbeat hardcore, the landscape after was much wider reaching. Labels appeared across the country, each releasing regionally unique offshoots of the genre.

Part of the charm is the genre’s complete lack of an attention span. Whereas more traditional dance music genres allow ideas to gestate, slowly building with a sense of musical literacy, the most fascinating breakbeat hardcore jarringly welds five different ideas together within the space of one song. Any sense of coherence is left at the door; violent jump-cuts, both musically and tonally, appear throughout tracks with reckless abandon. Emotions collide in a blur; every ecstasy-baiting drop of joy is rung from rampant piano chords and wailing diva vocals, then suddenly dread hits you like a train via sci-fi/horror samples and ominous pads. A track such as “I Feel So High (Welcome To The Ruff House)” by Hellrazer demonstrates this unhinged approach to composition. The samples are sardines together in a nauseating fashion, resulting in a visceral, satisfying and, ultimately, exhausting experience.

As time went on, underground hardcore producers embraced the allure of the dark side, and this tonal shift began the development into jungle music. The early releases of producer Mad Dog present an interesting arc, highlighting the gradual transition, as well as original hardcore labels such as Formation Records moving on to become jungle, and later drum and bass powerhouses. Foundational Jamaican sound system elements became more prominent and, in many senses, the direction of the music became more refined. Dystopian themes became prevalent, batting away the naïve ‘smiley face’ rave of only a few years prior. The breakbeat became the central focus: contorted beyond recognition, a tool of infinite possibilities. Kodwo Eshun explains in his book More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction that “…the producer is the scientist who goes deeper into the break, who cross the threshold of the human drummer in order to investigate the hyperdimensions of the dematerialised breakbeat”.

Where on earth breakbeat hardcore truly became jungle is difficult to pinpoint. But this period of transition, of tonal and musical development, is perhaps the most fascinating definition of hardcore to me personally. A period in which the producers had refined their craft enough to abstractly mirror the socio-political climate of the times, but before it had become too formulaic and overtly ‘musical’ (see: late nineties drum & bass), unrestrained creatively, delivered rough around the edges and unsurpassed in its gut-punch effectiveness. I often think of this period as an answer to the avant-garde sampling pioneer Pierre Schauffer’s oft-quoted “Why should a civilisation which so misuses its power have, or deserve, a normal music?”, and really, what’s more hardcore than that?

~~~

Part 3 – We Are From Rotterdam: The Birth of Gabber

“Hardcore didn’t really exist back then, house was just a bit rougher” explains Francois Maas in an interview for the documentary Uniform – The Dress Code of Dutch Hardcore Culture. Gabber emerged from Dutch slang translating to ‘mate’, which was initially coined gabber house, as the spirit within the community was sociodemographic. The style hadn’t been properly established in ‘92, where you’d find these records released on house labels whose frenzied atmospherics stuck out like a sore thumb. Early Rotterdam pioneers like DJ Paul, DJ Dano, The Prophet, Buzz Fuzz, Gizmo and The Darkraver mutated the doomatic construction of Planet Core Productions’ sonic mould with bleep techno rhythmatised melodies and Belgian techno’s UK breakbeat relationship, which transmitted an impenetrable sound barrier, illustrating the city’s breakthrough on the global dance music circuit. Rotterdam soon became the stalwart of the gabber movement and used their position to power an abrupt and uncompromising statement sound.

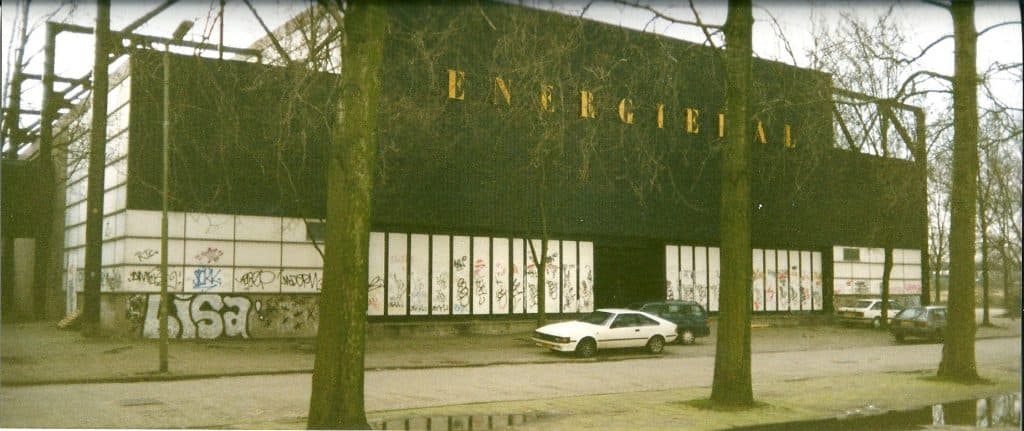

Energiehal, Rotterdam

The Lifestyle of a Gabber

Each city in Holland had its own gabber venue, Energiehal was Rotterdam’s stomping ground which was quite literally just a sportshall. Clubs weren’t typically the correct space for gabber as the style was invented as a youth counterculture. “The normal clubscene was a forbidden place for people wearing Australians”, referring to the tracksuits worn from the brand L’Alpina, typically worn by ‘gabbers’. “It’s our armour and our culture. It’s part of our identity” explains Nikita Sarukhanov in a 2018 article for Dazed, a young gabber fan from London. Those who would associate as a ‘gabber’ would use the aesthetic of fashion, hairstyles and dancing as subcultural language. The identity was so important that over 1800 Thunderdome wizard tattoos have been registered under Thunderdome parties. The ID&T imprint Aussie was also named after these tracksuits. Nike Air Max were a staple footwear with the tracksuit, and whilst they became synonymous with gabber’s identity, Nike refused to sign a collaboration for Thunderdome’s 25 year anniversary, contrary to their deals embedded in hip hop culture. Perhaps Dutch hardcore wasn’t enough of a cultural capitalisation, going by its mainstream media depiction into the late 90s, associating gabbers with fascism and football hooliganism, contrary to the perspective of original pioneers and promoters.

L’Alpina logo tattoo – Never Sleep Archive

Thunderdome: The Final Exam

The iconic Thunderdome parties sparked the beginnings of a subcultural legacy: parties held in giant sports arenas with teens hakke dancing to 160-200bpm braineaters. Imagine an end of year prom taking place in hell, replacing pressed tuxedos and diamante hair clips with tracksuits, shaved heads and ecstasy. These parties were run by Dutch media house ID&T, who originally started out as kids throwing a graduation party for their school finals. After booking ‘The Dreamteam’ at Thialf in Heerenveen for their first official party as Thunderdome, this event made Dutch dance music history and kickstarted gabber’s megarave experience that would soon permeate global micro-climates of up to 30,000 punters. The Dreamteam were some of the original gabber producers, consisting of DJ Dano, DJ Gizmo, Buzz Fuzz and The Prophet who released on the first Thunderdome compilations from ‘93 under the Dreamteam Productions label.

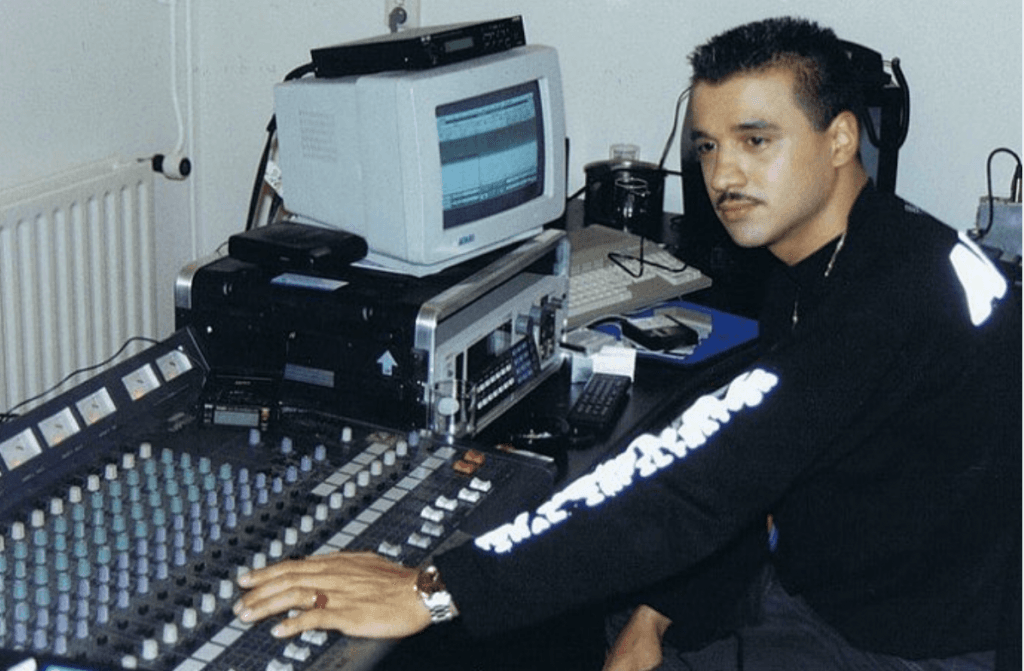

Early InnovatorsIt’s easy to get lost in the four-to-the-floor uninterrupted rage of gabber and to forget its past. Its pioneers were totally committed to the Chicago hip house scene and breakbeat heritage that lent its rhythmic assembly to breakbeat techno. Gabber used MCs religiously and repurposed the hip hop format for their own crowds. Listen to the EP Father Forgive Them by Holy Noise, a trio originally made up of Paul Elstak, Rob Fabrice and Peter Slaghuis, one of the projects preceding their journey to 160bpm. The track combines the amen break with samples from Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar, hinting at the ironic and gimmicky arsenal of gabber sourcing directly from its creators. Fabrice describes how when he and Elstak played the demo in the Mid-Town Records store, “The store owner from across the street got so angry that he drove his car to the front entrance and started gassing his car in the shop entrance”. Elstak was soon producing on his solo moniker DJ Paul, where his music was considered too hard for Holy Noise and Midtown, so he founded Rotterdam Records in ‘92. The Rotterdam Records artwork was often artistically outspoken, particularly the Euromasters releases with a giant industrial cartoon character urinating on the city of Amsterdam. This symbolised the two cities’ rivalry and Rotterdam’s attitude towards the club crowd in Amsterdam as typically being of higher social snobbery. Elstak was a pioneer in his own right, but was equally rooted in DJing alongside DJ Rob, where he helped communicate the ‘gabber house’ sound by making cassettes for the club Parkzicht, which would play harder music from 6am onwards. Elstak had a family and mentioned that he was never a ‘gabber’ for this reason and was solely focused on the music: a metaphorical father figure for the surging youth cultural movement which handed him the title as the godfather of Dutch hardcore.

Paul Elstak in his home recording studio – @ukgabbers Instagram

Tartan Techno

The dutch hardcore scene had a borderless relationship with the UK’s musical influence, notably the Scottish bounce techno movement or ‘tartan techno’. Babyboom Records, an imprint of Combined Forces, acted as the springboard between Rotterdam gabber and Scottish bounce, coining the substyle funcore. Scott Brown aka The Scotchman released “Happy Vibes” on Babyboom which became one of the most saccharine digital bounce tracks played across the north east rave circuit. Shoop!, one of the understated Scottish hardcore labels channelled the sacharinism but also encompassed the erratic churn of substyles. “There’s no real strategy as such, I just put out what I like and let the punters decide” mentioned Gordon Blair (aka DJ ZBD) in an interview for M8 magazine in ‘95. The Dutch and UK rave scene were friendly neighbours as they shared a mutual passion for this obscene sonic pylon, which intertwined with the megaraves of acid house and UK happy hardcore taking place across the country. This style wasn’t the only mutation of hardcore, as Belgium had already become an alchemist in the introduction of hard trance.

The Legacy of Bonzai Records

Bonzai Records was the biggest dance music label in Belgium. Established by DJ Fly in ‘92 after running the record store Blitz in Antwerp, the label sought to grow a family of DJs and producers that would push a harder sound in the local clubs. In no time Bonzai’s blended model of hardcore and trance aka hard trance, transcended the small city of Antwerp and reached parties as far as the USA. Frankie Bones describes DJ Bounty Hunter’s first release on Bonzai as being “the seminal Brooklyn Classic which rode thru STORMrave and then later Park Rave Madness scenes’ ‘, penetrating the Midwest’s party circuit. The first release from Stockhousen aka Liza N’Eliaz, a trans Belgian hardcore producer who went on to release gabber records with the likes of Thunderdome OG DJ Dano on Mokum Records. This record didn’t pack a punch for Bonzai in the clubs so they went back to the studio to revise their sound. The follow up was Thunderball which gave Bonzai a position in the commercial charts. “The principle was simple … everything that was made or produced in the Bonzai studio was automatically released on our label” mentions DJ Fly in a documentary for RedBull Elektropedia in 2017. This attitude followed the spirit of hardcore: more, more, and more. The label seemed less of a typical creative process and more of an assembly line, with producers hot seating and churning out records in less than one day. Jones & Stephenson’s “The First Rebirth” was made in 15 minutes. “We did everything on a W30 Roland workstation … you could only sample 4 or 7 seconds with that … our floppy disk ran out of space”. This process made the Bonzai tracks simplistic, yet this was the apparatus that formed the music’s oozing charm. Their aural makeup came from trance, inspired by early pioneers like Jam & Spoon, but wanted the sound to compliment the megaraves that were taking place. Space and sound became synonymous and interdependent, relying on post-industrialism to embody a sonic matrix capturing liberation and challenging prerogative.

Bonzai Records 1st Birthday flyer – Phatmedia

~~~

Part 4 – Outer Europe: New York and the Midwest

In the early 90s a hardcore hub was growing, alive in antagonism towards the police and forming spaces of sonic radicalism. This was New York and the Midwest, fronted by artists like Frankie Bones, Lenny Dee, Rob Gee, DJ ESP, DJ Delirium and DJ Repete.

Stormrave: a Frankie Bones Story

In a Resident Advisor Exchange podcast with Frankie Bones (brother of Adam X), he spoke of New York as the origins of the breaks scene, born out of a period of austerity, where graffiti culture and DJing collided and acted as the vehicle of the birth of hardcore and rave in the US. A defining moment here was the Bonesbreaks records on Apexton’s imprint Underworld, influenced by Todd Terry’s iconic house sound that made its way to the UK rave scene in ‘88/’89. The transnational exchange of dance records is what gave New York and the Midwest a stake in the hardcore league of legends, introducing the rave scene which Bones described as “breaking into abandoned warehouses”. The track “Peace Love and XTC (The Stormrave Story – Hardcore Remix)” features Bones’ own lyrics describing a typical experience at the short but legendary series of Stormrave parties he hosted, a diss at Joey Beltram and a sample of Genlog’s 1992 track “Mockmoon”, a hard trance classic from Germany. The sound of hardcore became symbiotic with warehouse venues and had an interdependent relationship, relying on each other to fuel a hedonistic and rebellious culture of ravers. “They brought together a bunch of people that weren’t supposed to be together” stated Bones, describing football hooligans from the UK and racial divides from Brooklyn which incited his PLUR message. ‘92 was where the sound became harder and the proto records Bones along with many others had created, inspired a young Lenny Dee to carve out a pantheon of hardcore techno.

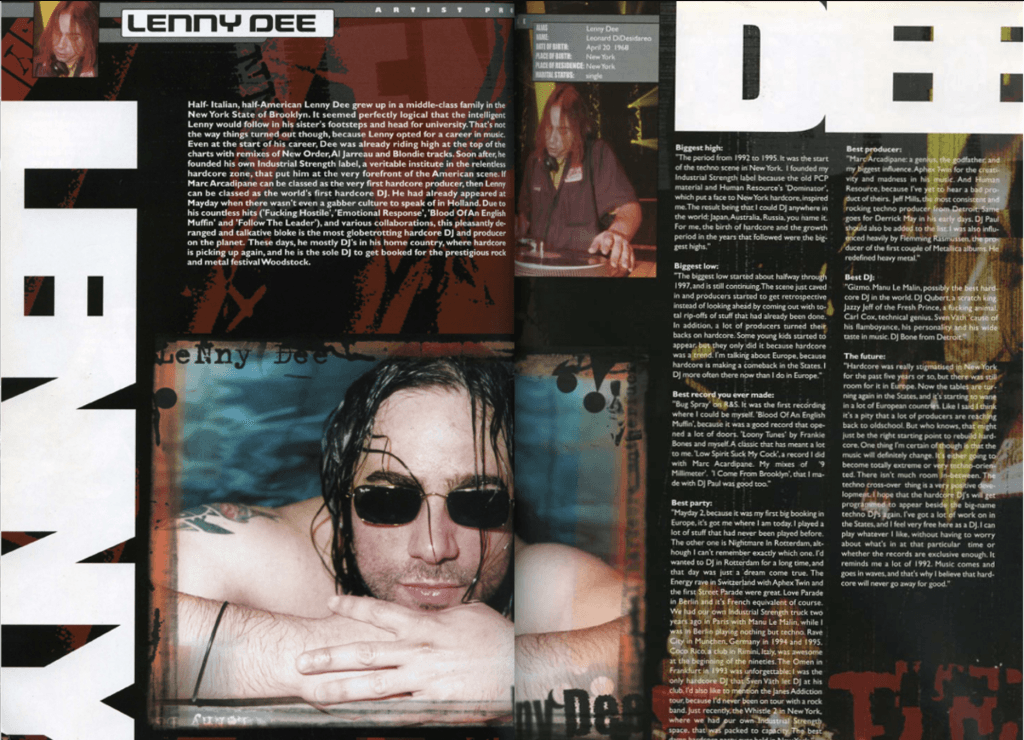

Industrial Strength: The Superlative of New York Hardcore

Dee, the warlord of hardcore techno, was at the forefront of New York’s underground music scene. Outlined in a profile spread for Thunder magazine, “he had already appeared at Mayday [festival] when there wasn’t even a gabber culture to speak of in Holland”. Dee was one of the first hardcore techno DJs to hit the circuit and had such a differentiated disposition in his sacraligic style, he was the only DJ at the time to be booked for Woodstock festival, embodying punk and metal sound design with electronic music. He began his own label Industrial Strength Records in ‘91, the first release being a repressing of Marc Trauner’s “We Have Arrived” which brought the early European hardcore techno sound to the states after he had listened to it for six hours straight when meeting Marc at a party in Frankfurt. This press influenced Lenny Dee greatly and kickstarted the heavier hardcore movement in the US, influenced by Dee’s continual touring in Europe. His repertoire is unbeatable, working with the likes of Rotterdam Records, Shoop!, Twisted Vinyl, Edge and Mokum, as well as identifying underground artists like Scott Brown, movements like Newcastle hardcore from Australia, and collaborating with established producers like Rising High Records’ Caspar Pound. “Lenny Dee is so far out on the tip of things his butt must hurt like hell” explains DJ Jackhammer in a 1995 interview for M8 magazine, describing his ability to propel the potential of hard techno onto the extrinsic fringes of possibility.

Thunder Magazine: a party in pictures 1996-1999 – Industrial Strength Archives

Midwest Gabber

Europe was a playground for experimentalism in the US and gabber was no stranger to the Midwest. Rob Gee is a gabber DJ and producer from New Jersey, whose background began in hip hop, metal and punk bands where he’d find himself touring with groups like Slipknot and System of a Down. His productions built on his previous experience in bands trussed with original vocal samples, the ‘NRG’ jingle to be played at gabber raves, which was widely accepted by Dutch producers, putting him on the European circuit. His style connected gabber to New York alongside DJ and label head DJ Repete who ran the independent label 12 Gauge Records. His knowledge and involvement in both the punk and gabber scene simulated the crucial message of hardcore, which he explained in an interview for The HARD DATA in 2016: “the beats might be brutal, but the message is positive”. A review of his EP Gabber Up Your Ass released in 1994 on Industrial Strength Records encompassed the performative nature of gabber’s character: “Rob Gee stage dived on me at Fubar in Sterling and nearly knocked me out. Great record”. Gee’s obscene scores fused Dutch history with that of the Midwest punk scene, like slapping two movements into a recording deck to be met with radically synergised output, less than sophisticated slapstick sounbites but surprisingly popular.

From House to Acidcore: Even Further into the Stratosphere

In a 2015 feature for Red Bull Music Academy, Michelangelo Matos wrote of Minneapolis’ musical heritage in conversation with Strouth who mentioned “that first wave [of Minneapolis DJs] was mixing acid house with Skinny Puppy” with a lot of artists jumping from dark industrial to house music without understanding its historical context. “That’s how we got a lot of our kids back in the ’90s, from those [local punk and metal] scenes, you know? That’s why we pushed the angle that we did, with the darker imagery and the tongue-in-cheek stuff. It resonated with the people going to these parties because that’s the scene that they came from” mentioned Kurk Eckes, the organiser behind Drop Bass Network in an interview with Tone Madison for the 25th anniversary of Even Further. Being influenced by European artists like Marc Trauner, together with the local punk scenes that curated a D.I.Y environment initiated an era of acidcore thrusting forceful reverberation through colossal bass bins. The amalgamation of these subcultures birthed a sea of promoters, such as Kurt Eckes and Woody McBrides techno pagan ritual Hell Bent, an event which took place at an illegal squat that has since burnt down as a result of the Black Lives Matter protests. “Burn baby burn” wrote Eckes in a personal statement on his Facebook page.

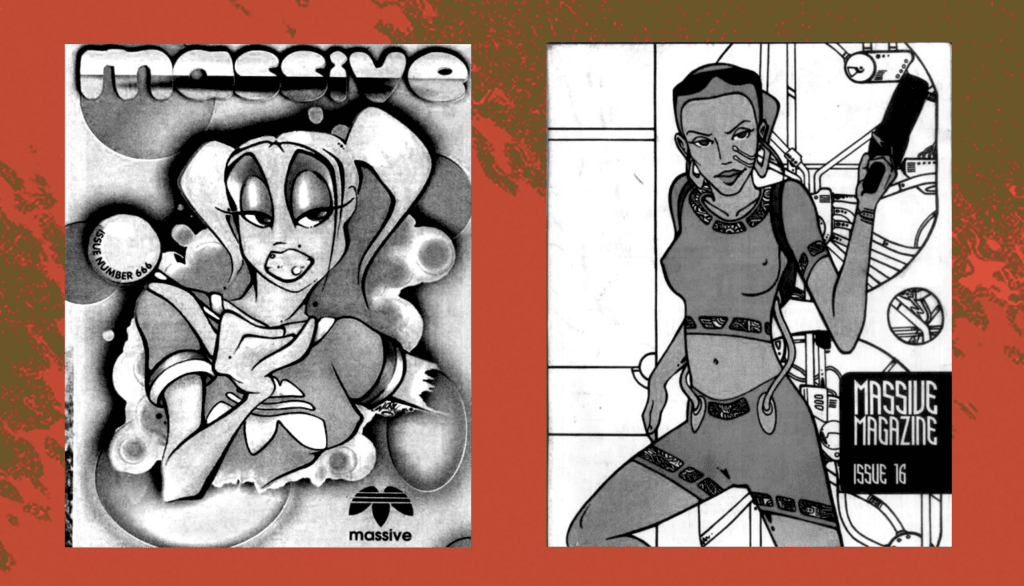

Even Further 1995 festival flyer – i-D magazine

Even Further was a free rave that took place in rural Wisconsin, a teenage pilgrimage met with glacial temperatures and wades of mud in symposium with rag tag stage design, where people would use cups to catch the leaking rain through the tent and speaker stacks would have to be hauled out a foot of mud (Spin, 2013). This captured the sheer D.I.Y nature of the festival, with little need for high octane production:; the music spoke for itself. “I don’t remember it being so much a musical experience. I remember it being kind of a war zone. People were just fucking high. I mean really high” proclaimed Will Hermes, Arts Editor of Minneapolis City Pages, describing the nature of the large gathering. The 1993 outbreak of gabber in the American Midwest was a sonic exchange between grassroots industrial techno labels and the influence of European hardcore. “What really fires the pleasure centres of this mostly Midwestern, Minneapolis/Chicago/Milwaukee crowd is the stomping four-to-the-floor kick drums of hard acid, as purveyed by Brooklyn’s Frankie Bones and Minnesota’s Woody McBride”, is a passage from Simon Reynolds’ Energy Flash: a Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture, a book which describes the discourse between UK jungle and the acceptance of young American ravers at the free rave Even Further. Whilst Woody McBride wasn’t a gabber head, he was divisive in the introduction of acidcore, something that acted as a springboard between techno and hardcore. In fact, techno went through a face of being rebranded as ‘tekno’ as the music became so hard (We Call It Techno!, 2008). Listen to the track “Ace Frehley” from the 1994 EP Bad Acid – No Such Thing released on Drop Bass Network. Hardcore didn’t just spawn in the US from the migration of techno to darker roots, there was an omnipresence of jungle and drum ‘n’ bass, for instance Dub Shack’s enigmatic cassette mixtape catalogue, which served to permeate the existence of the rigid 4×4 structures that were diluting the Midwest’s hip hop lineage. In a ‘93 Milwaukee-based rave zine Massive, an excerpt from “Brian” called The Hard Truth was strongly against the hardcore techno parallel stating “hardcore is breakbeats, hardcore is not tekno … raves originated in England with hardcore (breaks) not tekno. While there is hardcore tekno it’s still just tekno”. This derails the idea that hardcore can subsist without the presence of breaks.

Cover pages from the Midwest zine Massive – Never Sleep Archive

Part 5 – From UK Hardcore to Frenchcore: Under the Underground

Whilst terrorcore naturally developed as a substyle of gabber, the sounds of UK hardcore techno have been devisive in channelling sephucral ADD fueled sensory clipping, levitating hardcore’s potential to power ectoplasmic dynamism.

Take Lenny Dee and DJ Edge’s *10 EP on Edge records, a shining representation of the intersection of breakbeat and techno hardcore as well as the scenes in New York and the UK. “Silence of Eternity” couples the growling saturation of outer mind Belgian techno with a classic breakbeat, whereas “Alpha 1” focuses on a brain squelching 4×4 gabber remedy, which made an appearance in Thunderdome’s Vol. 4 compilation. The only thing it leaves out is any sense of euphoric melody, which propels hardcore away from the influence of the acid house and happy hardcore era, summoning unique definition. Dive into the Edge Records catalogue and you’ll find a collaboration with The DJ Producer aka Luke McMillan, who had been spinning since ‘89 under DJ Quickcut and affirmed his moniker as The DJ Producer in ‘94. The EP *13 samples DJ Bountyhunter’s “The Survival” record, further diluting the origins of hardcore into a saturated hoovermatic dimension. As unassuming and mysterious as his alias is, he went on to develop the label Rebelscum with Deathchant honcho Hellfish and Manu Le Malin, a byproduct of the frenchcore movement that had been established out of the rise of freetekno festivals in France (led by the free rave transnationals Spiral Tribe).

Frenchcore recontextualised the elements of hardcore techno and gabber, typically spinning at 200bpm, channelling a faster, darker and introspective identity, despite the sound being highly overt. Often the hardest music represented the greatest release from internal repression, otherworldly and cathartic representative of finger pinching scart noise. Simulating a kind of tonal dissonance in part resonated into harmonious cognition, examining a plethora of dispositions that could even be described as industrial trance as an offshoot of its mutational dimensions. This aural debris was developed by early hardcore producer Radium aka Daniel Técoult, who ran the label group Audiogenic which pushed the French sound of hardcore, inspired by artists like Kraftwerk, The Prodigy and Lenny Dee. Psychik Genocide and Dead End Records were some of the most popular, the latter under his duo alias Micropoint. The releases from these labels formed sounds that were similar to that of scraping the bottom of the oil barrel, extracting the final resources on earth to soundtrack our dystopia. Al Core’s “Dreams of Nightmares” captures each intricate component, an industrial trip from the depths of despair, and Angel Flo’s “The Kain Vampire” sonically evaluates how it really feels like to be in the deepest entity of a k-hole. The label names, artists, EPs and track titles often had obvious connotations towards war and violence, like genocide and terrorism, which was a direct comparison towards the industrial era of the 80s, creating rhythmic noise that simulated a resistance against evil in the world, challenging the optimism of moving into a new millennium.

Learning from the original’s of Chicago acid house, Brooklyn hip hop, UK bleep and Belgian new beat, it’s no wonder that hardcore endeavoured in tonal divulgence. Its subcultures shared a unique spirit, binding communities for one night that would otherwise never interact and communicating messages that were cryptic, only for the most visceral of beings to truly resonate with. There is something in that sentiment alone that is both irreplaceable and unreplicable. Subcultures will come and go, but one thing is for certain: hardcore will never die.

Listen to the second episode of Biodegradable Soundsystem here:

Authors

Eleanor Bickers is an electronic music enthusiast and writer based in London. She runs the Biodegradable Soundsystem series on Threads Radio, exploring the symbiosis of written, verbal, and sonic communication. In her spare time she often finds herself DJing, raving, and imagining alternate realities. You can find her on Instagram: @lnr_dj

Oskar Jeff is a producer and DJ under the name Dome Zero, who hosts the monthly Tinned Heat show on Soho Radio and has seen releases on Das Booty, Classical Trax and Sequel One Records. He is also a regular contributor to music publications Loud & Quiet and The Line of Best Fit.

Back to home.