“FREEDOM” by Reginald BoClair

I met Reginald BoClair in May 2023, through the Prison + Neighborhood Arts/Education Project Justice, Policy, and Culture Think Tank at Stateville Correctional Center in Illinois. Reginald and I bonded over shared interests in political philosophy, Chicago house music, and seeking the abolition of the US prison industrial complex. In this piece, Reginald leverages his background as an Imprisoned Black Radical, Abolitionist, and Deep Howze Muzik Head to argue that Deep Howze Muzik is an Afrofuturist practice that opens the door to a world without police. The piece interweaves analysis with scenes and lyrics from the world of underground Chicago Howze Muzik clubs in the 80s and 90s, from which Reginald relates his first-hand experiences. On the dance floor, he intimately lived out what he later came to understand as queer culture, Afrofuturist fugitivity, Black feminist masculinity, and healing from trauma; touchstones through which he now navigates Black life in social death, in the belly of the US carceral system. Elsewhere, Reginald has said: “Though sentenced to die in prison, we are alive.” My hope is that this publication of his work will be an enduring reminder of the vibrant, brilliant, undeniable aliveness of all those who are sentenced to die.

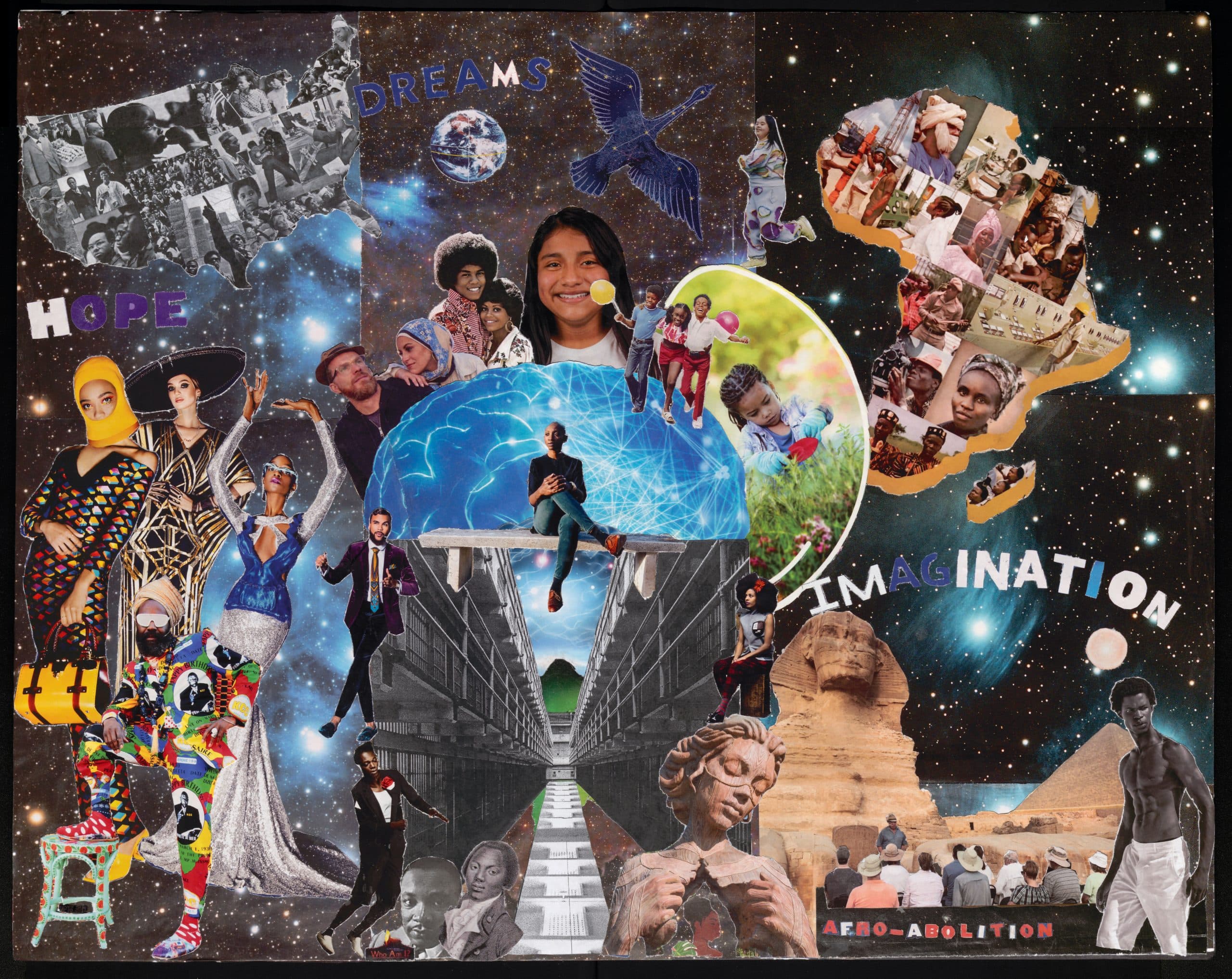

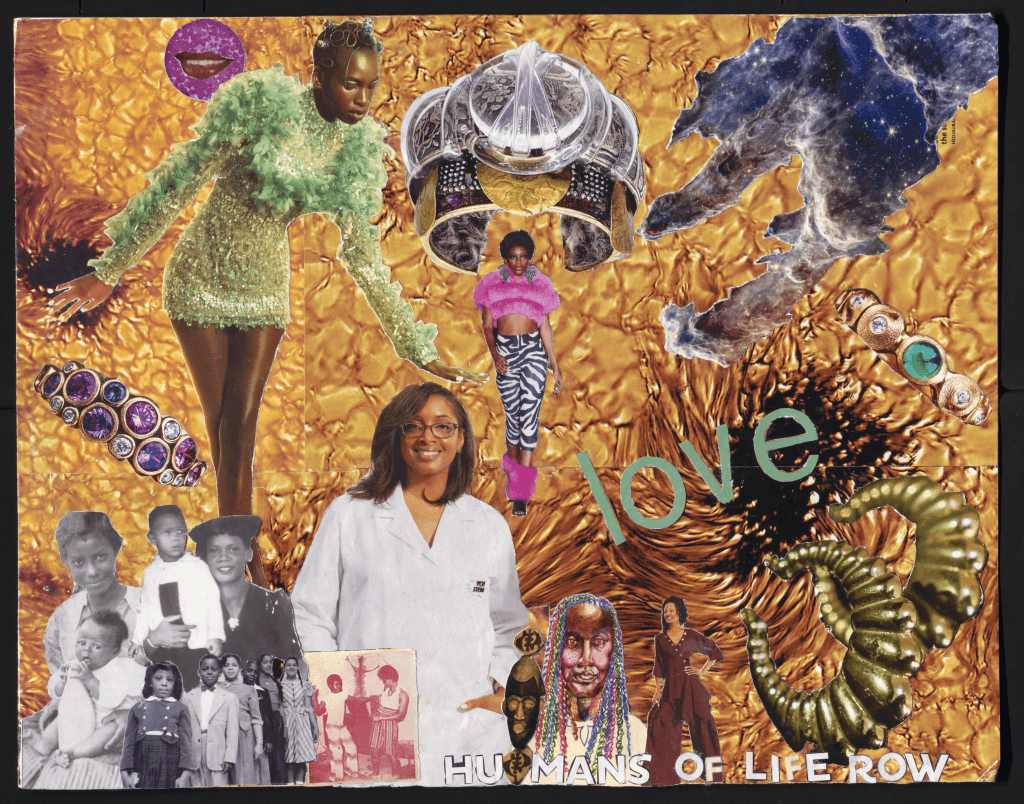

Reginald BoClair. Community. 2024.

Reginald BoClair is a graduate of University Without Walls at Northeastern Illinois University, Class of 2022, with a Bachelor’s art degree and a depth-area in African-Centered Transformative Justice Education. He is also a published collage artist, poet, and writer. You can learn more about Reginald and his work here.

“Freedom”

(Deep Howze Musik, Afrofuturism and Abolition)

by Reginald BoClair

This article is written in the tradition of the imprisoned Black Radical. The imprisoned Black Radical tradition is Black radicalism created and mobilized under conditions of imprisonment and incarceration. (Wilson, Rodriguez, and James 2022; Bryan, McMillian, and LaMar, 2022). The Black Radical Tradition displays the “collective wisdom” (Robinson, 2000) that has emerged from [Blacks] fights against human domination (Bryan, McMillian, and LaMar, 2022). While the Imprisoned Black Radical Tradition is central to our understanding of the Black Radical Tradition (and some might even argue that they are one in the same), it is unique in that it produces texts and epistemologies that are not necessarily tethered to academic scholarship (Wilson, Rodriguez, and James 2022; Bryan, McMillian, and LaMar, 2022). As an Imprisoned Black Radical, I wrote this article to be read as a collage or mix of a composition, and not in the traditional way. If you want to fully embrace what it is I am saying in this article, do it to the “muzik.” ¹

Music has always been a part of the Black experience in America. It has always been a medium used by Blacks to mediate perseverance through the desperate reality they faced on a daily basis. Whether in the fields during slavery, in the church amid Jim Crow, or contemporarily incarcerated in the Prison Industrial Complex, Blacks have consistently used musical agency as forms of resistance and meditation to overcome the moment and perpetuate a futurism.² Black scholars have held “because of (Black’s] musicality, Black subjects embody the harmonies and melodic archetype of U.S. democracy” (Weheliye, 2005). In other words, the Black aesthetic is capable of bringing people together. In this essay, I propose to show original Deep Howze Muzik (emphasis is mine in the spelling) is a form of Afrofuturism, and both are Black aesthetics of fugitivity (Harney and Moten, 2013), and can be informative to Prison Abolition practices.

“We’re going to bring down the wallsLet ’em fall, fall, fall, fallWe’re going to bring down the walls.” ³

Imagine a space devoted to overcoming the moment. A space where no matter what is going on in your life, being in this space gives you hope it will work out, and tomorrow will be even better. Why? Because this space is about “feeling and sounds, and logic is not [necessarily] required” (MacMillian, 2023). This space is only a box. Here the walls are painted pitch black, illuminated only by the glare of strobe lights flickering on and off. Hot and sweating bodies are pulsating, crowded wall-to-wall caught in the trance of the Black gaze while entrenched in a valley of sounds. To most of the sweating bodies this space is like a church filled with hope, happiness, and love. Where the DJ engages in a pastoral type call and response with the sweating bodies (a.k.a. the Congregation) through sound and feeling. The one continuous sound created by the DJ mixing recorded music from different genres (R&B, disco, funk, and gospel to name a few) whose pounding baselines beat the sweating bodies of the Congregation from the tops of their heads to the bottom of their feets. Meanwhile under the soothing, sharp, clap of the treble lay inspirational lyrics being sung, mentally evoking other world realism. The ambience of the “muzik” has your soul captive, and in that moment all things are possible. This is freedom becoming tangible. This is original Deep Howze Muzik, where love works no ill toward its neighbor.

“You treat me rightI’ll be good to youYou treat me rightSay it ain’t no game, It’s a love thang” ⁴

Chicago’s original Deep Howze Muzik is a spiritual genre of music created by the Black and Latino Queer Culture in the very late 1970’s. Marginalized and othered, this culture pushed back in organic resistance to heteronormative social constructs that saw their social angst transformed into a safe space of sound, expression, and possibility. The creation of this unique style of “muzik” was sensual and unapologetic about being inclusive to all who had the courage to patronize the space. Its uptempo rhythm and groove spoke a universal language of liberation to all who heard it, as it easily transcended the Black and Latino Queer culture that gave birth to the “Howze Muzik Nation.” I first met “Howze Muzik” in the early 1980’s at the age of fourteen. I went with a group of friends to a club called “The Playground a.k.a. The Candy Store.” My life changed forever. Howze Muzik was love at first sight for me. I had never known what it was like to feel uninhibited until that late night/early morning. Having grown up in a strict, marginalized, single parent home on the Southeast side of Chicago where money was tight, space was tight, and I was both the baby and only boy. For me as a teenager, Howze Muzik was quite the revelation.

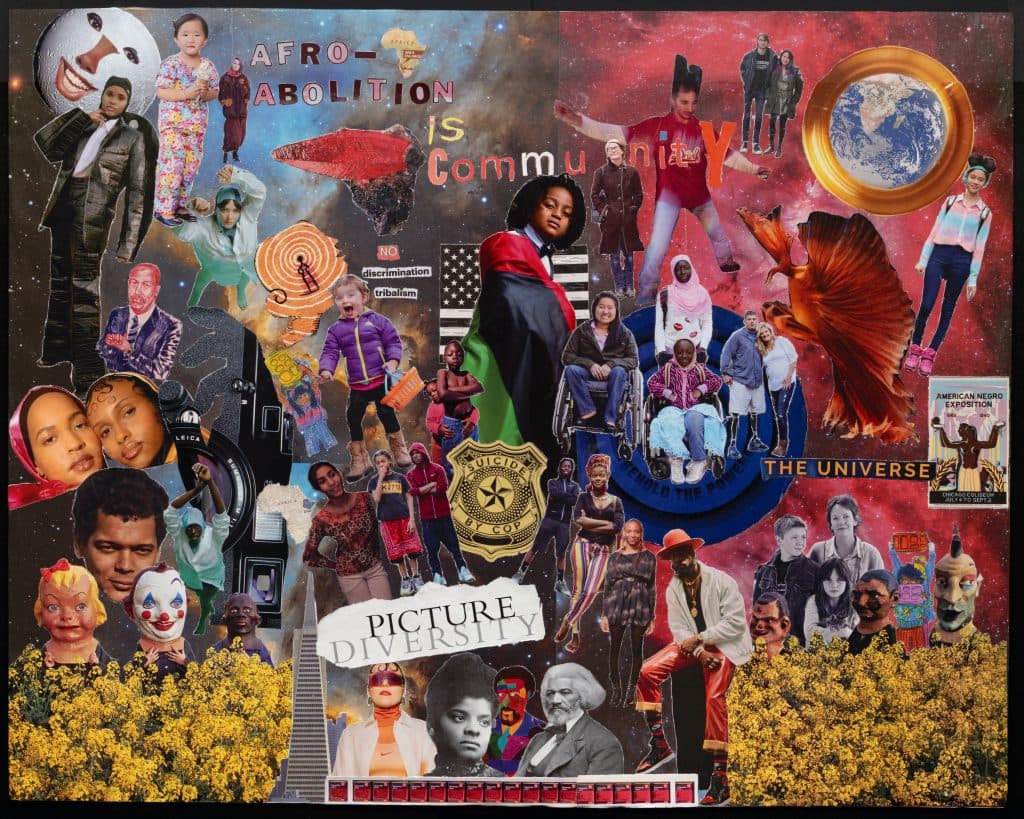

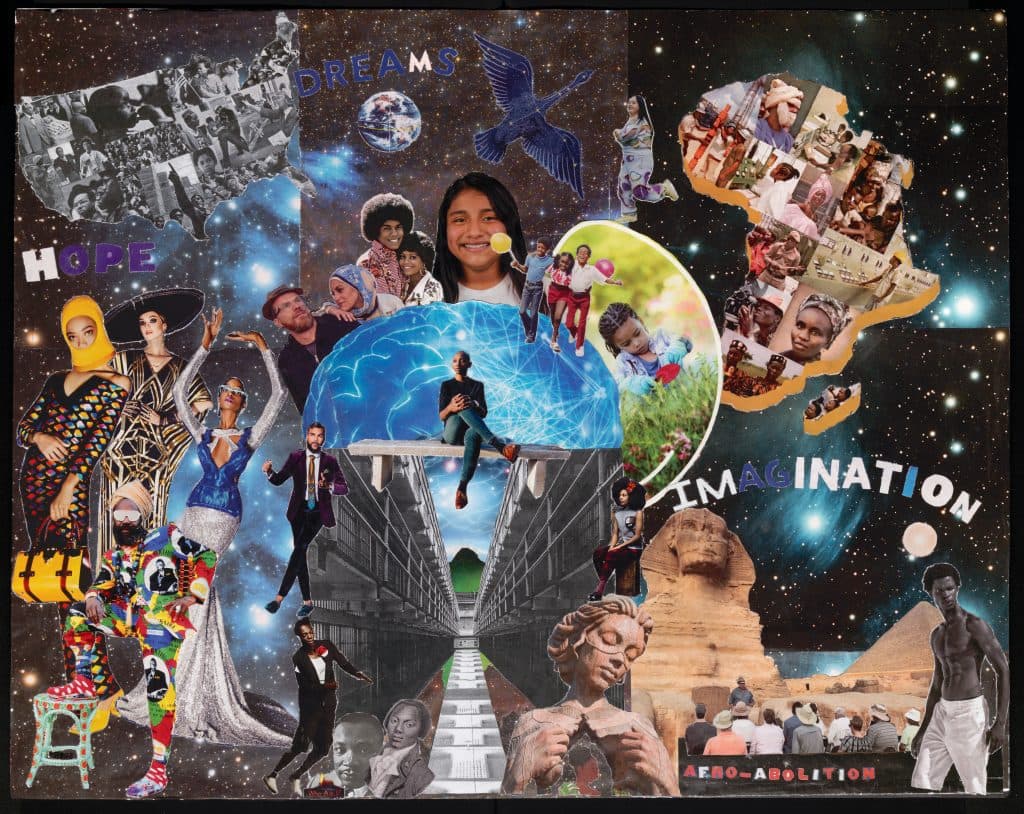

Reginald BoClair. Hope, Dreams, Imagination. 2024.

However, it was only after being exposed to a club called “The Underground aka. The Muzik Box” did I truly become a “Howze Head,” a “Deep Howze Head.” The original Deep Howze Muzik played there was innovated by a DJ named Ron Hardy whose style of spinning “muzik” was exciting, imaginative, and extremely creative. The environment was my initial introduction to myself and the Black Queer culture that embodied spiritual and sensual freedom. The atmosphere of the scene, the Deep Howze Muzik being played, and the queer culture around it changed how I saw and felt about myself. I gained even more confidence in who I was in this moment, as Howze Muzik changed how I saw the world while mediating my late adolescence/early young adulthood. And so began my life as a Howze Head that continues unto this day.

Fast forward forty plus years, and I see Howze Muzik as still viable, even now more than ever before. As a social application, Howze Muzik evokes fugitivity (Hamey and Moten, 2013) for all who experience it, for Blacks instantiating an Afrofuturism in historic continuum of Black aesthetic. As a social agent, Deep Howze Muzik has helped me navigate “Black life in social death,” (MeMillian, 2021) and can be instrumental in Abolition by bringing people together from all social constructs (race, religion, sex, and gender) and be a communal safe space for expression and dialogue. To Black scholars, this process is known as “the mix,” and “the mix can be found in a number of different spaces and times…in the construction of twentieth-century Black culture”(Weheliye, 2005). To original Deep Howze Muzik, the “mix” is essential in this genre of music being named as such. It was the mixing of various styles of recorded music at a club called “The Warehouse” that gave the new sound its name “Howze Muzik.”

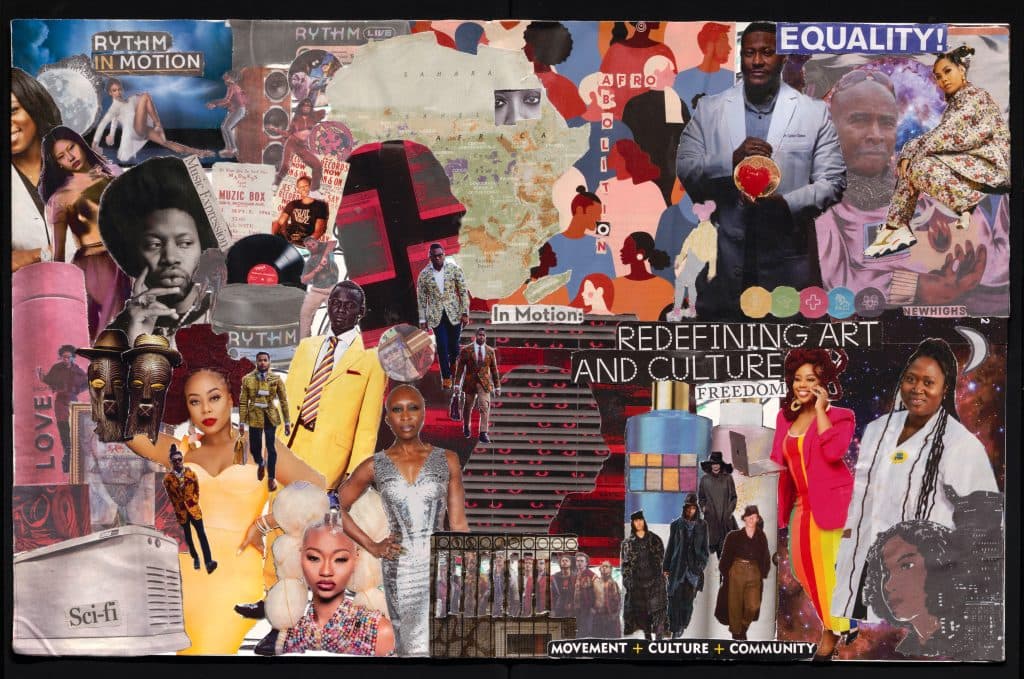

Reginald BoClair. Rhythm in Motion. 2024.

However, the original Deep Howze Muzik was only played initially at certain underground clubs in Chicago (and was not initially called Howze Muzik). It differed from the public version of house music played on the radio and popularized by the DJ group “The Hot Mix Five” who were well known in Chicago during this time. Nonetheless, Howze was a nation, a movement, and a way to be. We all could co-exist in the love of/for the “muzik.” Us Deep Howze Headz—as we were known—had a saying back then: “real Deep Howze Muzik brings the woman out of a man, and a man out the woman.” This saying spoke to the queer, gender neutral, and inclusive culture that we Deep Howze Head embodied in dance and style of dress.

“Brothers gonna work it outBro-thers gonna work it out” ⁵

The early DJ pioneers of original Deep Howze Muzik were Afrofuturist. They used technology (turntables, the crossfader, reel to reel tape players, equalizer, speakers, and lights) to remix and reimagine various styles of recorded music to transconsubstantiate the moment, and create transformative spaces of escape and freedom. According to Black scholar Alexander Weheliye, the “mix” brings together “disparate elements… [and] offer a strategy for the construction of a world without prisons” (2005). In the “mix,” ‘original Deep Howze Muzik.

Reginald BoClair. Welcome. 2024.

Afrofuturism and Abolition meet and align in the margins of their common interest. Their common interest being a world free from racism, prisons, social binary constructs, exploitation, oppression, and violence. Combined they offer humankind an alternate possible way of being incarnate.

“Now don’t give him no peace sign if you don’t mean it from your heartUnited we can get over but yet we’re still apart.” ⁶

Original Deep Howze Muzik foreshadows Afrofuturism through a praxis of fugitivity from subjection. Afrofuturism is a term coined in the 1990s by cultural critic Mark Dery, and is defined as the Black imagination envisioning a better tomorrow against the circumstance of today. While most Afrofuturists contrast tomorrow with technology and counter narratives against anti-Blackness, as an imprisoned Black radical, I see Afrofuturism through a different lens. I’m not saying their definition is not valid because there is no one definition of Afrofuturism except it embodies Black aesthetic. Nonetheless, I see Afrofuturism as a struggle to escape the day-to-day Black experience in America of which technology may or may not assist. I see Afrofuturism as a way to keep believing in myself, persevering in social death as I’m subject and forced to endure a continuous disproportionate treatment at the hands of anti-Blackness. Yet, somehow, someway I find a way to another day. This is both Afrofuturism and Fugitivity. Fugitivity has been described as “the tension between the acts of flight of escape and creative practices of refusal, that undermine the category of the dominant” (Campt, 2014, McMillian, 2023). Because the original Deep Howze Muzik has a Howze nation of listeners from all constructs of society, these partakers get to experience escape and maroonage as liberated communal praxis creating life—a futurism.

“We must all joining handsWe can march across this land in peaceLove and joy without understanding is a true loss.” ⁷

Original Deep Howze can be instructive to scholars, community organizers and educators on how to bring people together in community with no domination. Abolition is first envisioned. and then a world without prisons is created (McMillian, 2023) Prison abolition is about deconstruction of the Prison Industrial Complex in the social construction of modern temporality; Creating lasting alternatives to punishment and imprisonment. Because “the abolitionist is an alchemist… by alchemy (it is meant) a significant transformation in political agency toward the pursuit of freedom” (James, 2023). As an Imprisoned Black Radical (who opposes capitalism and imperialism), and one who is also an African-centered Black feminist Deep Howze Head, abolition aligns with my worldview. This is especially true when I understand how cultural transformation is critical…in the process of social transformation” (Carruthers, 2012). For this reason, I envision a future past confinement; a transformed society free from hegemony and retribution. A society that is socially mutual, the same as an original Deep Howze party, where Black feminist masculinity and a healing centered engagement of trauma (that seeks to address the residual effects of patriarchal masculinity) are the norm (Ginwright, 2019). A society where the focus on harm reduction has led to sustainable material differences being made in the lives of the marginalized, criminalized, and othered. A society free from hierarchy, violence, and misogyny. One informed by how Blackness operates as the modality of life’s constant escape (Harney and Moten, 2013). All because last night a DJ saved my life.

“Houses made of ecstasy around the roomSo picture us together now picture us together nowFeeling all our dreams are freeRomantic thoughtsand not letting them fade awayReach for the sky” ⁸

The DJ can be compared to a pastor of a church. This person technically and audio-haptically narrates the setting. As the DJ spins the set, this person’s mixing, blending, and editing of recorded music to create one continuous sound that allows “(he congregation” to feel and ride the beat, while effecting a technically induced temporal spirituality transforming one’s subjection. As the DJ pushes and pulls the bass and treble of this one continuous sound creating both highs and lows—which is known as “beating the box”—where “the commodities speak” (Moten 2003), and “souls [are made] audible and legible” (Wehchye, 2005), producing sounds and spaces of freedom. A historic sound in continuum of the subject Black experience in America.

Reginald BoClair. A Mother’s Love. 2024.

If you listen to the lyrics in most Deep Howze songs, you’ll see they are about coming out of the walls society has built for us (Harold, 2019). Upon lofts builts with wooden floors, original Deep Howze Muzik has been pushed and pulled creating both highs and lows similar to the elusiveness of the American Dream for most Blacks and others who instead only have freedom dreams, that take place in the communal ambiance of Original Deep Howze Music. “It could be in any neighborhood. An underground Black room with only a strobe light [to illuminate it.] [It could be in] a hotel room or abandoned warehouse” (Harold, 2019). Here you can find original Deep Howze Muzik instantiating Afrofuturism, and creating spaces of freedom to envision a world without prisons.

Howze is a spiritual, transcendent, and euphoric inducing agency informing the imagination. The ultimate reality is in the hands of the everyday people and their willingness to become involved in the fight for social change. The uncertainty of this gives rise to the speculative fiction’s dichotomy of utopia | dystopia, which, in essence, is the truth of possibilities indicating the interconnected and interacting opposites that constitute the dual nature of life as we humans know it. Through original Deep Howze Muzik humanity can be made aware of other ways of being, a fugitivity and maroonage. Original Deep Howze Muzik, Afrofuturism and Abolition, these are my vehicles to human freedom, what are yours?

“Love,love, love, love, loveWill bring us back together for-ever” ⁹

Footnotes

1 I define “muzik” as a way of life, a way to be. It’s more than simply music.2 Futurism invokes something more than the moment. 3 “Bring Down The Walls,” Robert Owens.4 “Love Thang,” First Choice.5 “Brother’s Gonna Work It Out,” Willie Hutch. 6 ibid.7 ibid.8 “Paradise,” Change.9 “Love Will Bring Us Back Together,” Roy Ayers

References

Bryan, N., McMillian, R. LaMar, K. (2022). Prison abolition literacies as Pro-Black pedagogy in early childhood education. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy Vol. 0 (0) 1-25

Campt, T. (2014). “Black feminist futures and the practice of fugitivity,” Helen Pond McIntyre 48 Lecture, Bernard Center for Research on Women, Columbia University. 7 October, 2014 Lecture recorded on video

Ginwright, S (2018, May 31). The Future of healing: Shifting From Trauma Informed Care to Healing Centered Engagement. https://ginwright.medium.com/the-future-of-healing-shifting-from-trauma-informed-care-to-healing-centered-engagement-634557c69c

Harney, S., and Moten, F. (2013). “The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning + Black Study.: Brooklyn: Autonomedia, print

Harrold, M.L. (2019) ‘Growing Up in Chicago House Music.” Chicago Review Vol. 62/63, No. 4½, The Black Arts Movement In Chicago: 257 – 262 online

McMilian, R. D. (2021). “I Believe In Living*: A Curriculum of Black Life Amid Social Death Of The American Prison State. The Graduate School Miami University Oxford, Ohio

McMillian, R. D. (2023, March 23). Conversation over phone.

McMillian, R. D. (2023, May 14). Conversation over phone.

Richie, B., Davis A.Y. Dent, O., + Meiners, E. (2022). “Abolition. Feminism. Now.” Chicago: Haymarket, print

Robinson, C.J. (2000). “Black Marxism: The making of the Black radical tradition. University of North Carolina Press, print

Rollefson, G.J. (2008). “The RobotVoodoo Power Thesis: Afrofuturism, and Anti-Anti-Essentialism From Sun Ra to Kool Keith. Black Music Research Journal Vol. 28, No. 1, Becoming: Blackness and the Musical Imagination. Center for Black Music Research. Columbia College Chicago and University of Illinois Press. 83-109 online

Weheliye, A.G. (2005) Phonographies: Grooves inSonic Afro-Modernity. Burham-London: Duke University Press, Print

Wilson, S., Rodriguex, D., + James, J (2020, August 24) “The Roots of the Imprisoned Black Radical Tradition.” https://www.aaihs.org/the-roots-of-the-imprisoned-black-radical-tradition

Back to home.