I smell a Rat by James Ess

A short piece of experimental theory-fiction by the reclusive author James Ess.

noun: rat; plural noun: rats

INFORMAL•NORTH AMERICANa person who is associated with or frequents a specified place.“LA mall rats”

Thousands digging parallel trenches, somewhere in the Nevada desert. The foundations of a city lie vacuum-sealed in pyramidical formations, while hulking machines ferry craters of dust towards the horizon. As the sun rises over a forthcoming culture of strip malls, cheap food and endless countercultural echoes, cement, water and aggregate are mixed together in parts 3-1-2.

I-beams – stacked in units of thirty-two – arrive from the other side of the globe, appearing overnight. Blindingly reflective, glass sheets are dragged from beneath flapping dust cloths on the backs of mottled convoy vehicles. Casino signs are Chinooked in by the military, crowning each compound before the carpets have even arrived from China, so that everybody can come to terms with the cultural ossuaries that will remain here, and start to accept the fun that they’ll all have among their pre-mortified innards.

***

Arid, hazy desert time: there’s no telling how long we’ve been digging for. To the West lie America’s famous sites of entropy and psychedelia: Zabriskie Point, complete with philosophical day-trippers, psychedelic bands playing along the dotted horizon line, and others on simple, unintentional drifts – journeying through rather than to, in flashy muscle cars named after even more muscular animals – finding the only thing comparable to the sheer horizontality of the landscape to be time passing itself; exceeding itself through entropic neutrality, scored by explosions of guitar and the same wail echoing indefinitely across the flatlands. People stray from a tour-bus covered in Day-Glo paint a few feet, taking photos of the horizon and utter nothingness. A geology older than air: stalegtital pronunciations jut at impossible angles along a dry lakebed’s piebowl crust, mimicking the peaks that form the outline of the city behind us: mirroring the skeletal fractures skylining against the same blue expanse. There is little shadow to speak of, making it hard to tell the time. The local temporal drift plods lazy and thick. You begin to come to terms with the age of the place by counting the rings of erosion on the towering rockpiles, as with trees – except this time you multiply their number by infinity to the power of however long we’ve been digging for.

***

The carpets arrive, and men in teams of two unfurl them down impossibly long corridors bisected by mirrored suites, themselves hiding ceramic kitchenettes harmoniously framed by floor-to-ceiling, double-glazed windows. These penthouse screens present a time-lapse: gradually materializing panoramas of grey living blocs outside, stood in the gridded formation of American streets and stretching into the distance, themselves visibly saturated by material goods and luxuriously textured objects in their own windows: lurid fruit bowls, pre-set tables, electric juicers, fridge-freezers, flat screen televisions, surround-sound systems on minimal metal frames, faux plants, walk-in showers, pre-fabricated Scandinavian furniture and grand pianos hoisted up the thirty-something floors via the elevator shaft. These postmodern renditions of living quarters start to silently overshadow the sun, while vast layers of virtualized strata supporting crystalline Helicopter pads in the heavens emerge from the imaginary. The rich above, while smaller quarters sit untouched (untouchable) below: exclusive housing for shells of former objects. Relaxation lounges for the executives, smoking rooms, private pools, billiard tables, tiled balconies, meteorite fragments on display and vast penthouse suites: the works. At their saturation, these spaces are nullified into stage-sets beyond the cinematic frame of the windowsill, while the desert floor outside becomes punctured by acres of scaffolding set in cubic football pitches of concrete. Physical palimpsests; reliquaries devoid of meaning: apartments pose as horrifyingly still life-sets mimicking film-sets.

Their vacant expressions interrupt us,switching the assisted Steadicam functionality of capital’s dreamwork to OFF;an interrupt to the dull seance of cybernetic consumer blissthrough the making-overt of corporate infrastructure’s co-option of the human desire program[or, the hijacking of the human mainframe and the consequent short-circuiting of our perceptual relationship between ugly pig iron (material) and beautiful windowsill vase (product).]History repeating itself through a precise dementia,stuttering to interrupt its own body once more:hysterical dress-rehearsals fall into cycles of indefinite degradation in cyberspace –arms flail in the calculated surfas all becomes subsumed by the waves of online capital.[.obj’s recalling the wreckage of a CG ship bob in the Piratebay. Wooden shrapnel rear ended; cuddled downwards by a kraken’s tendrils.]When the tide withdraws, the beach is laid bare once more,complete with the same empty shells, pebbles, and seaweed:the same signifiers, only rearranged into enticing new shapes and volumes.

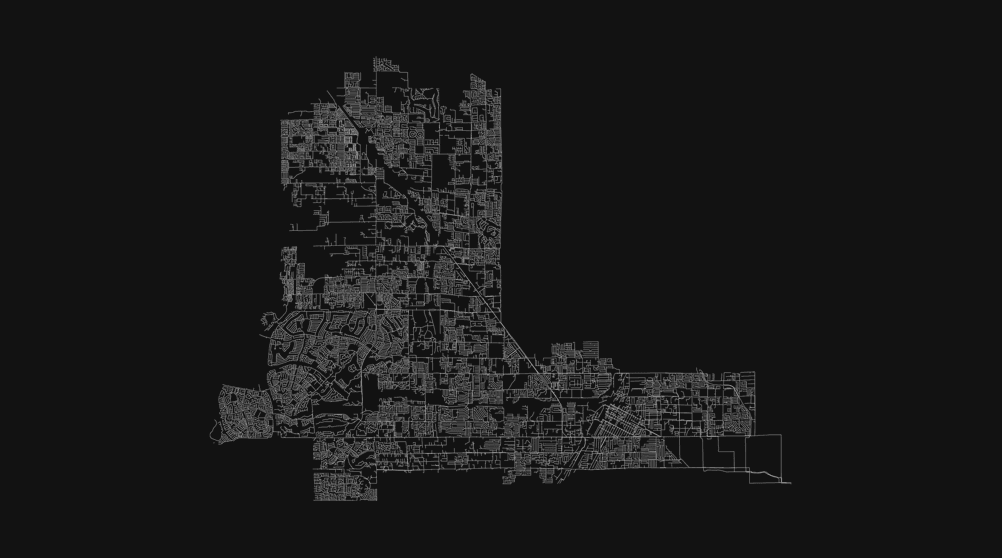

The trenches – as tentacular infiltrations into what will soon be condemned ‘suburbia’ – now skirt the perimeter of the city-cum-pyramid, where the scale and value of the living-units crescendo among the hubbub of the metropolitan lunchtime rush. Digits emerge perpendicular to the main thrust of the excavation, filtering beneath the pencil outlines of housing projects sitting in silent anticipation, or cul-de-sacs sitting in pre-destitution. The monolithic epicenter is already a young and increasingly accessible Vampire, thanks to an interlocking formation of tunnels and above-ground monorails, which swathe widely, coalescing across the enclave. Aboard, you can already smell the traffic smog and the street food below. An olfactory tour of urbanization in a glass bottomed carriage; the streets retaining all the allure of a torn-down perfume advert, soiled and sullied and set to drift along sidewalks as a contemporary stand-in for a tumbleweed. These twisting metal rails contrast the hand dug lines, the man-made marks, and the unspoken importance of their future as storm drains in the arid desert; their potential to be a future haven beneath the soon-to-be streets.

Oranges sit, piled in the metal canopies of juicers, ready for the first commuters into the city. Somewhere else, a solar farm twice as large as the city durges its unending end-note.Four hundred miles North, a dam starts to burst after a rubber LED seal in one of the display units allows a small amount of break-time coffee to filter between itself.The ancient homestead which occupies the highway some miles back quickly undergoes a drastic neotokyoization, while holographic replicas of Easy Riders arrive from out of town, cruising the still-steaming tarmac.A thick soot spores from cartoonish balloons in a parade led by the local constabulary, steeped in riot-gear and carrying black-market Kalashnikovs, marking the official completion of the city.Children sing in unison, their futures already accomplished.Blizzard-white lattices unfolding in the synaptic recesses of increasingly mechanized minds — as the bulbs of solar-powered street lamps flare behind the eyelids — as the smell of scored carbon proliferates the nostrils.This is the formation of a big multinational from the ground up. A mirage unfolding, shimmering in the stillness: postmodernized; neotokioized, Meccanized; blindingly formal.And a newspaper from the next decade reads that there are now hundreds of people living full-time in Las Vegas storm drains.

1. a rodent that resembles a large mouse, typically having a pointed snout and a long tail. Some kinds have become cosmopolitan and are sometimes responsible for transmitting diseases.

The insane strata of Westminster Tube Station feels like an attempt to replicate a portion of the Death Star, or at least its 1977 movie set. Commuting between the giant staves, looking up at the beams and cylinders of frosted metal, an empty mood proliferates the walls no matter how populated the space actually is. Misty surfaces reflecting ghostly silhouettes: everything is either machine textured or textured by machines. The beams – bolted in tension – seem hardly enough to support the soil beyond the arcs above, yet denote some kind of functionality, dwarfing the human by presenting it within some brute mechanism, as if we’re all passing through some colossal flintlock weapon, cocked and releasing at any moment. The tunnels below are surprising respite from this architectural intimidation, permitting intermittent gusts of warm, stale air through the passages. This air – pushed and pulled by oncoming rail traffic – erupts like water from a geyser, occupying the shape and volume of the next station it inhabits. Escalators function similarly, carrying bodies from transit to more transit via stationary transit, or to their destination at street level via a coffee vendor.

***

An aside:Trains are production time catalysts: demanding our digital mind-spans while we wait, and commanding our productive attentions for the very fact that they sandwich the working day between two temporal units (of travel), functioning as the most physical version of a binary machine switch possible. A productivity machine machine. Whenever the image of ‘tube’ or ‘tunnel’ springs to mind, many imagine a cylindrical hole which stretches for miles in pitch dark. This is a ruse, and in truth, people should consider inner-city train networks to be more like a split lane motorway, where vehicles and bodies are displaced and distributed in opposite directions AT THE SAME TIME. In the visual imaginary, tunnels should appear less as single, wire-like structures, and instead tend more towards the dual barrels of a conventional shotgun. The lost coordinates of what we imagine tunnels to be must be reclaimed firstly by learning that they are split in two, like a record’s A and B sides, or a brain’s two hemispheres.

***

Geysers of people springing up across the city through a rat warren of interlocking tunnels. Like rats, tunnels run in tandem beneath the city, travelling in packs, clustering, and becoming tangled at an epicenter. Rats, too, ferry passengers back and forth. In proportion to the scale of a human standing in a train carriage, these approximately manifest on rats’ terms in the form of fleas (famously), viruses (again, famously) and rat lungworm, the larvae of which are transmitted via fecal parasites. Angiostrongylus Cantonensis is found exclusively in rodents, being transmitted between them regardless of species. Similarly, rats carry their own brand of gastrointestinal parasites, which – again when equated to the human scale – act as microscopic tapeworms, parasitically digesting in order to grow and breed. Recent scatological studies have revealed that these Halminths are also transmitted fecally, emerging instead from egg clusters which lie dormant in deceased rats’ shit, coming unlive in order to devour the next intestinal tract they find themselves inside of. In such instances, the rat – embarking on its daily jaunt beneath the gas pipes in a cavernous tunnel – keels over suddenly, shrieking in pain and shitting blood in an attempt to expel its passenger, Alien (1979) style. Again, imagining the scale of a human-in-train vs. a parasite-in-rodent scenario, the latter comes out on top in terms of contagion statistics. Conversely, the final parasite which occupies the space between a rat’s lungs and its anus is the single-celled Protozoa, a fungus which rapidly multiplies itself once inside the next rat’s digestive tract. Although these parasites are too weak to harm humans, they are capable of rupturing and perforating the skin of their rodent hosts, leaving weals which occasionally resemble the track marks of human drug abusers who inject.

Rats have historically represented the harbingers of widespread catastrophe, ferrying fleas – the blood of which carried trace evidence of the bubonic plague – by secretly occupying the bellies of trading galleons from Asia in the 1300s. The inaccuracy of nautical chartering at the time meant that these vessels often ended up in the wrong countries or even continents, which led to the plague gaining a foothold in Southern England (although recent studies have resulted in the idea that the original pathogen may have lain dormant in parts of Europe as early as 3000 B.C). Through generations of pack inbreeding, this virus has mutated, becoming distilled into a pulmonary syndrome known as Hantavirus, which travels through the blood, eventually collapsing the human lung infrastructure. Again, distributed fecally, the chances of contracting this disease are mercifully five times less likely than being struck by lightning, and half as likely as being eaten by a shark – a statistic which has become minimized since the trade routes of the Old World have long since been accurately chartered by satellite imaging technology, and there are now vessels which can steer these passages remotely (a trading-galleon Captain could now quite literally ‘do’ these routes with his eyes shut and one arm tied behind his back).

Within these ships, rats become both transporters and transported. A contemporary rendition of this stowaway scenario is the hiding of rats’ nests within the cavities of (especially wooden) walls, transmuting their base status by presenting themselves somewhere within the ecology of the domestic scenario. They are able to dislodge and chew granular substances into a fine pulp, which is combined with sticks and other manageable objects in order to create canopies which can permanently house up to twenty inhabitants. The occupation of the pre-existing space between wall-studwork-studwork-wall, or brickwork-lintel-lintel-brickwork is a smart choice, because its dimensions often ensure that it is a space that can be maneuvered and traversed with ease. This occupation also impinges upon ratkind’s broad status as a nomadic city dweller, having moved from land to ship to land again, and later from sewer to domestic space (or rather the space quite literally existing emptily BETWEEN domestic settings). It is in this way that ratkind simultaneously defies preconceived notions of its own status by redefining ideas around the micro-occupation of macro-space. Traversal is also especially important when considering that rats, like magpies, are collectors of things: silverware, decorative Christmas cracker bells, guitar picks, pin badges, memories, flakes of skin and other dead creatures, embalming them in their cud and enshrining them within piling mausoleums, commonly known as a ‘Rat Mountains’. (These arrangements are often found in sewer networks and storm drains too, although the objects involved in these collections tend – as the obfuscating nature of drainage systems would suggest – to consist of more abrasive materials: nude magazine fragments, syringe tips, rotten leaves, wet wipes and human shit).

***

Another aside:On this level, rats share an artistic tendency which is considered essentially human: undertaking the construction of assemblages through the repurposing or assisting of readymade objects. This idea harkens to a natural truth: that the production of an artwork is ecologically inherent in certain species – and further – that artwork necessarily starts with the collection of (not necessarily physical, perhaps memorial) facets that are combined and eventually knotted into a single end, which is then presented (or not presented) – its function laid bare (or not, until it is deciphered).

This nesting style is almost totally unnoticeable too, bar its few but distinctive sonic properties: the high-frequencies of rodent communication, and the shrill squeal of the maid in the kitchen on a chair with the broom, as she sees one scurry past early one morning. (Imagine the Cat and Mouse scenario of Tom and Jerry: According to several fan-websites, the duo are close friends – a fact which is forgotten ad infinitum by Jerry because of his short, rodential memory span. This idea would make sense in terms of several episodes in which both parties combine their resources and knowledge to defeat a common evil: dogs, other predators, cartoons from other universes or production companies, humans, etc. Supposedly, the reason Tom so avidly chases Jerry (and rarely actually catches him) is because he has been instructed to do so by his owner: Tom is the lethal means. If he dysfunctions, then Jerry’s life is prolonged. Tom plays the role of a sort of inverted life-support machine to the mouse, mediating Jerry’s duration via a trivial act which he must continuously commit to in order to maintain his cover as deliberate saboteur. The mouse is unknowing of this fact, and still fights for his life with lethal force. It is a modern tragedy of sorts, in which the episodic formation of the series is vital when talking about Jerry’s memory. As with many children’s cartoons, there is no continuity, no story – merely the links the viewer makes between episodes in their heads – an internal memorial device which is supplemented by similar overarching values, show to show. It is as if Jerry suffers from some kind of (theoretically pure, anterograde) amnesia, where he cannot fabricate new memories beyond the point in his life where he believed Tom to be his nemesis, and continually forgets about their renewed friendship, somewhen during the off-screen lassitude between installments). This, and the invisible tensions between the collected objects, curatorially vibrating along the common frequencies retained within each object’s history, and the memories etched upon their surfaces. Broadly: things inscribed within their presence AS OBJECTS, ruminating besides OTHER OBJECTS. And lastly, the subsonics of the nest blocking, resting on or dislodging a member of the house’s internal mechanisms (pipes, circuitry, structural support, etc.), leading to sleepless Winter nights thanks to the cold, which started with the noise of them there, somewhere, gnawing through the fucking tenons holding up the dining room floor… before it all fell through and got really, really cold, and nobody could understand why this had happened here, to us of all people.

The true horror of this nesting method emerges when the operation of the cud backfires, the mechanism trapping the rats along with debris, gum, sap, plaster, ice, hair, urine, dirt, blood and shit, forming a hardened, resin-like substance – rather than merely maintaining the nest’s intensely-labored structure. Although an uncommon occurrence, there have been reports of ‘Rat Kings’ throughout history: a phenomenon where the tails of two or more rodents become ensnared, knotted or stuck together, leading to a symbiotic existence wherein they hunt, gather, feed, sleep and breed in the same group with that which their tails are interlocked. Often found in the Winter months, when materials become hard, brittle and generally less forgiving, a trio of rats encased in the wall of an Estonian barn wake to realize that last night’s discharge has frozen behind them, actualizing the nightmare witnessed in their collective Winter dreams: the joint encasement of their tails. Struggling to escape each other in the frosty daylight, they begin to trample towards the outside, pictured between the barn’s weather-eaten slats. Their random movements of over, under, through and round lead to bastard sailor’s knots being cast by their tails, tightening alongside their struggle. Their tails emerge so intertwined that they can’t even glance over their own shoulder without spotting a sibling which they’re now permanently attached to. (This is much like the classic idea of having an angel on one shoulder and a devil on the other as a subconscious rudder for steering thought, except in this case they’re not subconscious entities: they’re all real-life devils which can never leave each other’s side(s). Animal knots are bad omens – particularly in the Biblical senses of the onset of plague, pestilence, etc.

***

***

Another aside:‘Etc.’ here can be reframed in terms of conquest, war, famine and death, and each of these framed in relation to rats commonly carrying diseases, where:

Conquest = The double-edged incursion of rats via the invasion of our homes and our encroachment of their spheres. Just as the parasites cling to their underbelly, they now depend on our development of public space and our greedy excess for survival.

War = The weaponization of natural ingredients into manmade poisons to control the spread of disease carried by the rodents, including but not exclusive to execution (commonly within baited traps which quickly transform into poisonous death chambers, or environments where the rat starves to death if forgotten about) and chemical (chemically induced) castration.

Famine = We put the bread away at night now.

and Death = The harboring of the diseases themselves, and the diseases’ ability to spread through the rats’ internal networks as they themselves spread through human social and architectural networks.

***

In many ways, this omen also plagues the Rat King itself. It is now three times as loud, and so remaining hidden is virtually impossible. Hygienically too, members now defecate proximately, and since they cannot hunt, their starvation causes coprophagia, which simply accelerates the induction of intestinal parasites into their own bodies. Furthermore, when one member bites it in a trap, the others must drag the necrosing corpse until they themselves too, bite it, or, less likely, they learn to untie knots. This body is never wasted though, as the others will turn to cannibalism for sustenance, which is far easier than dragging it through the pinhole in the larder wall.

Although there are disputes as to the authenticity behind the existence of Rat Kings – as hobbyists may have manufactured them in order to generate paranoia by foreshadowing the return of the plague – a European museum holds a carbonized group of thirty-two members, having been found in a farmhouse chimney stack.

***

(X-ray scans of this Rat King denote fragmentation of the cartilage in their scorched tails, suggesting a co-operative survival for an extended period. This is perhaps one of the closest things to a hive-mind operating in nature, akin in some ways to the rat, Remi, in Disney Pixar’s Ratatouille (2007), who controls a young chef by pulling the hair on his head in pursuit – essentially – of good food and wine, and hearty survival.)

***

The noise of thirty-two rats squirming, eating, fucking and shitting beneath the framer’s feet leads to a major renovation of the site’s original floorboards, revealing a hand laid mosaic-style floor. As discussed, traversal is key in ratkind’s repertoire of survival. Craftily occupying another space in the wall cavity, the plasterboard and the wooden slats supporting it are permanently dislodged in order to view the gradually accumulating nest by gas-lamp. Moving away from the light, the Rat King inhabits a space in the roof rafters next – a Lovecraftian hive-mind, squirming its way up the home’s innards and lying in wait above the master-bed. Obsessed with thwarting their movements through his home’s hidden passageways, the farmer finally chops the roof supports too, leading to a loud CRASH and a bump on the head, adding to the delirium. The winter daylight recounts shadows cast by black rafters, and before long all that remains of the farmhouse is a vague, penciled outline; a mirage of a former dwelling. How long has he been at it? Is he in fact chasing ghosts that he’s invented? The structure laid-bare, the reality of copper pipework and other INTERNAL MECHANISMS exposed, carpets all soiled and sullied by the elements.

***

(In a similar fashion to the examination of the tail cartilage, X-ray scans of the house-cum-warren reveal a tomography of hidden labor; of ancient nesting spaces, canopies consistent with recently lost objects, the sentimental qualities of which plague their owner’s minds, snapping them out of oneiric day-drifts (tea lights, small Buddha figurines, single earrings, bottle caps, broken glass – each surviving far longer than the man-made non-spaces of the structure); memories that trespass the minds of their owners, shattering collections and disorganizing arrangements: a new and chaotic taxonomy of objects.)

***

The torment of that SOME-THING, that MANY-FACETED-THING crawling through the house’s secret spots, until reaching its resting place of the brickwork chimney, where it’s accidentally barbecued almost beyond recognition. The specter of LEGION – both one and many – leaving its ectoplasmic imprint forever on the surrounding masonry, the smell of charred fur clogging the fractured remains of the farmhouse. The rot of these animals sinking – decomposing bodies falling from perches, between cracks in the floorboards and the non-space which supports the next layer of gravel above this one – above this concrete – above this topsoil – above this clay – above this rock – above this crude oil offshoot, leading to a cavern some miles away. Ghosts drifting through encrusted pipelines. Creeping as lubricant for the cybercapital whirlpool, since the dawn of the combustion engine. This ghost army will one day rise into the air, slow-cooked and carbonized over a thousand years.

The term ‘home invasion’ only seems appropriate when extrapolated from it’s contemporary, visual-imaginary counterpart of armored SWAT team members blowing doors off their hinges somewhere in a poor city neighborhood, while a secondary support team hiding on the roof parasails in through the windows. Conversely, rat infestations are far more subtle, impinging instead upon stealth, obfuscation, and no mistakes in the departments of sonics, the building’s structural integrity and structural discrepancies caused by the rodents to the essence of the property itself.

…

DEROGATORY•INFORMALa despicable person, especially a man who has been deceitful or disloyal.“her rat of a husband cheated on her”

an informer.“he became the most famous rat in mob history”

ACT 1.

[A kitchen somewhere in New Jersey. It is the kitchen of a wealthy family; 1990s chic set in the corner of a large, open-plan living expanse, and everything has its place. This area is divided, punctuated by a series of structural pillars which run through the space, supporting cream archways and leading to a lower living area furnished with cream leather sofas and coffee tables. The tone is generic, but denotes a vast wealth accrued, lost and gained again cyclically, over a period of many years. The majority of the kitchen surfaces are made out of American White-Oak, except the counter tops which are made out of a non-scratch, marbled jesmonite set within wooden boarders. Pearl-white tiles line the wall by the sink, and the ceiling is geometrically vaulted, which makes the space more airy and bright. The floor is also comprised of tiles, but these are of an off-white, almost yellowish pallor. Scratch that: the floor is made of smooth wooden laminate strips. And there are no tiles by the sink; merely a continuation of the jesmonite counter top which wraps vertically up the wall until the windowsill above the sink stops it from travelling any further.

Reading from screen left to right, a wardrobe-like unit houses a two-storey electronic oven in its belly, with two symmetrical cupboard doors above it, which sits either completely empty or filled with dishes and boxed appliances which are rarely used. The doors are perched at just over head-height, inlaid with the routed shapes of professional joinery. Above this, a small vent (which must be kept permanently switched to open for legal reasons) is installed. There are two cream hand-towels hanging – again, symmetrically – from the handle of the upper-most oven. There is nothing but a thin drawer a skirting-board’s height from the ground beneath the appliance, as the wooden shell must house and conceal the oven’s workings.

To its immediate right sits an alcove – the start of the counter-top running the perimeter of the kitchen. Upon this sits a small, white microwave. This section runs the width of three large, rectangular cupboards, both above and below the counter-top, which house two shelves each (twelve total) and eventually meet the unit which demarks the corner of the kitchen and the end of the kitchen’s shortest wall. Three-drawers-wide make up the space between lower cupboard and the underside of the kitchen surface. These cupboards either house nothing, or a selection of more commonly used plates or appliances. The drawers hold cutlery. All that is seen is lit by circular lighting fixtures in the angular cream ceilings which snugly skirt the cabinets, dictating the mathematical threshold at which the counter-top ends and the space between itself and a large kitchen island begins.

In the corner, the worktop houses a large, wooden bread-bin with a fold-up top, sitting at a forty-five degree angle. To its immediate left – on the boarder of the previous section – sits an electronic juicer. Above both hangs a version of the other cupboards – this time with a glass face divided into six smaller windows – in keeping with the router’s pattern. This visibly houses a selection of tumblers, wine glasses and crystal champagne flutes, reserved for special occasions. The door of this cabinet runs parallel to the flow that foot-traffic is herded in, through the surrounding room, and bridges the awkward gap from one wall to another, where two of the original large, rectangular cupboards extend ninety degrees perpendicular to the right of the first wall, and along the corner kitchen’s main wall, which is bisected by sunken window above a central, ceramic sink. Joining the underside of these two cupboards, and slightly more towards the side of the furthest one hangs a horizontal kitchen-roll dispenser, which sits just in front of three or four cookbooks, and, further right, what can only be a toasted sandwich maker and a more intensive food processer, the edge of which aligns seamlessly with the cupboard’s side, located above. These objects are of course sitting atop the same worksurface, but this time travelling ninety degrees right to its original direction.

The aforementioned double window divides this wall almost in half, with the left side from which we have just travelled appearing to be more heavily saturated with white goods. It runs a vertical line of symmetry from the center-line of the sink’s swivel neck when it’s set perfectly at a ninety degree angle perpendicular to the wall behind it. The windows sit sunken, bordered by a curved frame painted in a glossy white. The beveled inlets of each window house eighteen individual panes, which grants a generous view of a garden dominated by a swimming pool complete with a diving board, and a patio overrun by an excess of white, plastic, injection-molded furniture. The opal shimmer of the water glances off the surrounding furniture. At the head of the pool, to the left of the diving board, is a small, slatted, multi-storey hut – a dwelling for wild ducks. A small ramp runs down from the custom-cut stone ledge which encloses the pool, breaking the water’s surface. This scene is set before a backdrop of a tall, dense forest of dark-green firs. The leisure items in the foreground appear to be covered by a light mist, by virtue of their situation behind a net curtain. Above their frame sits a floral curtain, hoisted and tethered, which is rarely used to block this view of the outside. The cream angles of the skirting just beneath the ceiling have again been dramatically cut to snugly accommodate the folded curtain’s position, while simultaneously housing a circular spotlight in its roof. The sink sits above the traditional double-width cupboard, which, when opened, reveals the vital mechanism of the U-bend, several bottled cleaning products and yellow Marigold rubber gloves. This enclosure is topped by a single, wide drawer which runs its length and is situated directly above. This drawer does not actually function, instead operating to obfuscate the sink’s workings which will not need to be unprofessionally tampered with (unlike the blockable and easily-detachable U-bend). This assembly of cupboards is a defective clone of a set located immediately to the left of itself, below the counter, where the cookbooks and food-processor are still sitting (the defect here is that the drawers do not comprise one long, non-functioning space, but are two separate and functional areas, their edges aligning with the cupboard doors immediately below them.

To the left of the sink sits a selection of hand soaps and unused washing-up utensils. The sink doubles up as a waste disposal unit too, and there are some plates of half-finished meals waiting to be cleaned, complete with trace-evidence of foodstuffs. A small metal area for drip-drying such objects lies to the immediate left of the sink, which is cloistered by some small, glass spice-shakers and a wooden mug tree complete with striped, round-bottomed coffee mugs with striped patterns of deep-reds and whites, and flat-bottomed ones in alternating baby and sea blues. Next to this is a classic American diner style coffee maker, complete with glass coffee jar (and half a jug of cold coffee). Above these objects is the final head-height cupboard, which this time houses bowls, plates, and other objects which are more frequently used. The deep alcove of the window is reduced again here – as before – and houses a circular light just above the center of the cabinet’s routed door. Directly above this and sitting vertically on the wall is a circular vent which leads to the outside, to the swimming pool. The coffee equipment sits on the same green counter-top, although this section is less worn and remains partially hidden from daylight. Below this and to the immediate right of the sink’s double cupboard is a small, empty dishwasher, and further right still sits a final knee-high cupboard which sits below the skinniest drawer yet, complete with a visible wooden knob for access. Each component of this section ends at the same longitudinal point, where a large, black fridge-freezer stands, ending the corner-kitchen with a large wooden cap, again with the timeless routed pattern of postmodern joinery. The fridge is unevenly split: the left hand third is a door which hides the innards of an empty freezer. There is a ceramic magnet holding up a paper on the door’s exterior, below which sits a grey, inbuilt ice-cube and cold-water dispenser. The right hand door (constituting the other two thirds of the unit) protects the transparent shelves of a fridge, which hold Italian pasta dishes on large ovular plates and in glass trays, preserved and concealed by neatly-ripped Aluminum foil. There is also a selection of traditional Italian meats folded up in sheets of baking paper, and several American beers, cartons of milk and fruit juices in the fridge-door. This door’s exterior also frames papered information, but this time there are four or five sheets: calendars, letters and printed notices, each of which are held up by their own uniquely molded magnet. Above – but not in line with the seam between the fridge-freezer’s doors – lies a final set of symmetrical cupboards – above head height – which are slightly larger copies of the ones above the oven on the other wall, beset with the same routed design as all the others. Again, this holds items that are rarely used, such as platters and large bowls for parties and social events. Above the left hand door is another vent – a replica of the rectangular one from before – again permanently switched to open. The wall on which this vent is set continues to travel off screen right, presumably stretching above the dining room’s glass doors which lead outside to the pool.

The final component of the kitchen is a large, central Island which can seat up to five people. As such, it’s sides are divided into five equal, rectangular panels – each routed with the same motifs as the rest of the room – which sit below an overhanging lip made of the same material as the rest of the kitchen’s counter-tops. The skirting foundations of the furthest-right panel – which runs parallel to the wall initially discussed – sit in line with the fridge’s end-cap, stretching into the room for an approximate length of an average American man’s double-shoulder-width. This panel’s path is then bisected by the second panel, which sits at a forty-five degree angle – the same orientation as the glass-faced corner cabinet holding the glassware. This, again, stretches the same length, becoming bisected by a set of three panels which run parallel to the kitchen’s longest and most recently discussed wall, which stands ninety degrees perpendicular to the island’s first panel. In front of each of these panels – and slotting neatly beneath the overhanging lip above – stand four round-topped, waist-height, unpainted, conventional wooden stalls. These seat the American family at casual, transient meals such as breakfast. The lipped counter-top visually obfuscates the work surface which sits at the height of the panels. This higher level presents a large, round fruit bowl – devoid of any fruit – at its right-most point. A large, black folder (perhaps containing high school homework or property deeds) then appears to the left of this, alongside a biro laying among its open pages (colored either black or blue). The final object at this level is a small stack of white paper drinks coasters, on the far-left of the surface. Although unclear, there are presumably several cupboards inbuilt within the parameters of the panels which structure the island, which are no doubt made of white American oak, and are no doubt routed with exactly the same pattern as all the others. The difference is that their formation is unknowable at this point, while speculation on their positioning is useless (say, two double knee-high cupboards side-by-side, topped by two wide drawers (or four ordinary ones) and held up by a skirting board). Whatever they may be, they all end at the same longitudinal point, where the lower counter-top holds (from screen right to left) a large ceramic water jug, painted and glazed with a gilded blue pattern spliced with floral motifs; the tips of other pens sitting in a pen pot (again here, the colors are unknown); a metallic, cylindrical pot, containing larger metal cooking instruments which are too big to fit into the drawers, or, are perhaps required frequently (these include but are not limited to a small metal ladle, a large metal ladle, a wooden spoon, a metal whisk, a metal potato masher, a large plastic serving spoon, etc.); an American white oak knife block, holding nine traditional kitchen knives, the black plastic hilts of which are patterned by three structural metal polka dots, inlaid on each side; and finally a pile of ceramic vessels (plates, bowls) which are patterned with larger renditions of the jug’s motifs. I never noticed any plug sockets though.]

…

James Sibley (here writing under the pseudonym James Ess) is an artist and writer based in London.

Editor: Alex Honey

Back to home.