Ralf Hildenbeutel: EYE Q, Earth Nation, and Frankfurt’s 90s Trance Scene

In the first edition of a series accompanying her show Biodegradable Soundsystem, Eleanor Bickers spoke to the enigmatic electronic producer Ralf Hildenbeutel

All images given by the permission of the artist.

Last month I spoke with Ralf Hildenbeutel, a musician from Frankfurt who is a renowned film composer and electronic music producer. Although his career spans 30 years, I was keen to find out more about his experience as a producer and artist alongside Sven Väth and Matthias Hoffmann under EYE Q records, a pioneering trance label from the 90s. His classically trained approach to electronic music helped musically define an era buried within dance music history, which remains a symbol of Frankfurt’s burgeoning urban landscape in the early 90s electronic scene. From his live performance project with Markus Deml as Earth Nation, to his early studio days co-producing with Sven, the result of this conversation is a modest take on musicianship and friendship, clasped with nostalgia, owing to the rave decade that can never be recreated.

~~~

Eleanor Bickers: Thanks very much for taking the time to speak with me. It would be great to hear what you are up to right now?

Ralf Hildenbeutel: I still mix electronic and acoustic and everything but the last 10 years I have been focusing on film music, like limited series, films and feature movies. I’m still doing some electronic stuff like working with Chris Liebing on his albums for Mute Records.

EB: It’s clear you’ve had a pretty esteemed musical career over the past 30 years. How did it all begin for you and how did you fall into electronic music and your trance-related projects in the early 1990s?

RH: Originally I come from a classical background, largely the piano, and was later into pop music and bands as well. It was around 1990/1991 I met Sven [Väth] and the interesting thing was there were a bunch of musicians like Matthias [Hoffmann], Stevie B-Zet and I who came from the musician side and meeting someone like Sven who came from a different side, the combination in the studio made the whole thing different and special. It was fun and new for everybody, that’s kind of how it all started for us really.

EB: How did you get into this new progressive style of music and which artists were influencing you?

RH: Because I have a different background, besides the classical stuff I was listening to American and English synthpop and 80s rock stuff, not just electronic. It all just happened really. I was listening to all the typical electronic acts like Kraftwerk and Jean-Michele Jarre, but also synth rock bands such as Ultravox and Saga. When we all came together in the studio it was just about electronic music and the good thing is that we didn’t have so much influence before which gave us the opportunity to create new stuff.

EB: Would you say that perhaps you were some of the first people to be making trance music or were there other people making a similar sort of sound at the same time?

RH: Yes, kind of. There was quite a strong scene in Frankfurt and Berlin, and of course some other cities but these were the major cities in Germany. Of course, we weren’t the first ones doing dance music but especially this trance sound I would say the biggest impact came from Frankfurt and Berlin in 1991.

EB: EYE Q records seemed to be the label in Frankfurt that was pushing this new sound forward. Could you talk about how the label formed, your friendship with Sven, and what the label was doing differently at the time?

RH: I knew Matthias [Hoffmann] from before, before being the time before techno … the life before techno. I used to play with him and Stevie B-Zet in funk bands and stuff. He met Heinz Roth who had worked with Sven, when he was frontman for OFF, a disco dance project who had a big hit in 1986 with “Electrica Salsa”. Heinz was managing Sven these days as he was around a lot for TV shows. Sven was a pop star before he did techno basically.

The three of them worked quite fast to form the label EYE Q. Matthias called me and just said “you have to be on this, it’s the hottest shit ever, you have to meet Sven and everybody else”. Frankfurt is small, we were just sitting in a cafe talking and coming together and this is kind of how it happened. We just thought ok you should do music and you should do DJing etc. and one thing led to the other.

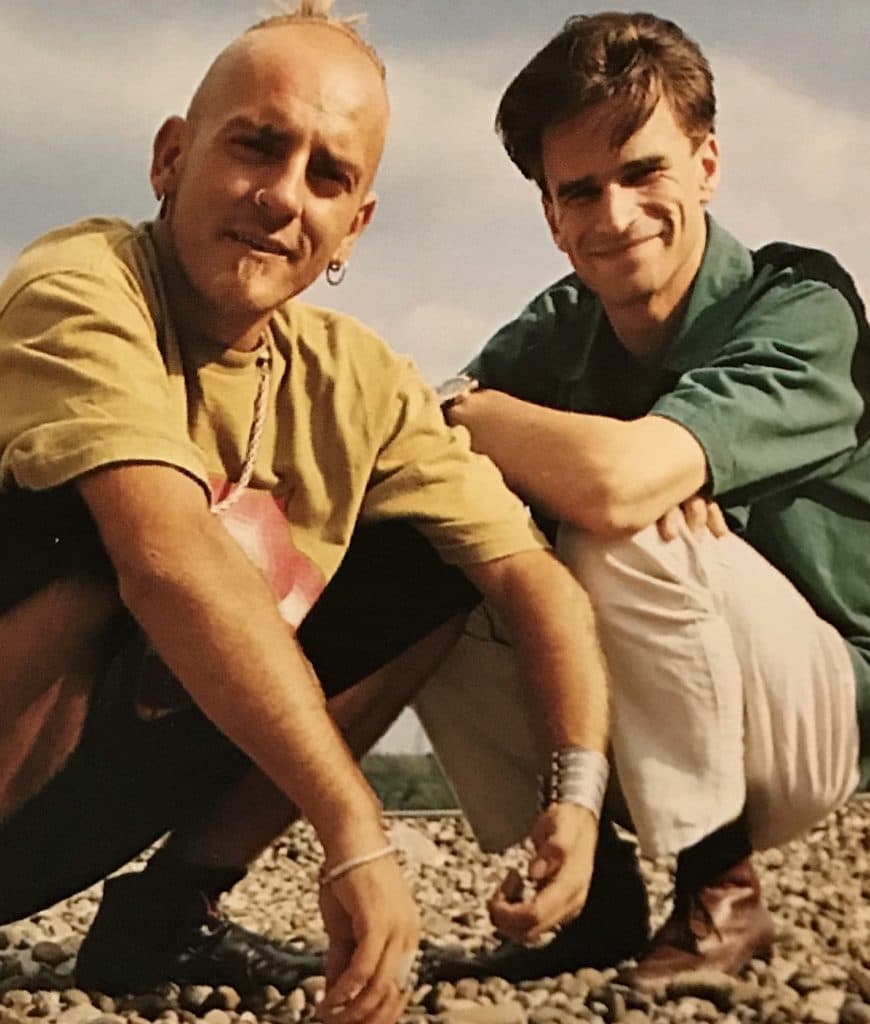

Väth and Hildenbeutel

EB: It sounds like you all had different skills and it was just a bunch of friends creating something that you probably weren’t even aware was completely new.

RH: Exactly, nobody probably would have thought that something could have happened like this one year earlier. We had this lucky situation where Heinz had a business kind of background, so he could do all the managing parts and we could focus on the creative part. Sven had already been DJing for a while, the more commercial ‘disco’ stuff. When he took over Omen, he started to play electronic underground music. There was the acid stuff, then came the techno stuff. It was all within one to two years where everything started to explode.

Producer wise it was me, Matthias, and Stevie B-Zet; we were the main producers for the label. EYE Q released the trance stuff and the sub label, Harthouse, released the harder stuff. Then you had Recycle or Die, another sub label which released all the ambient stuff. EYE Q had a major deal with Warner and they could just do whatever they wanted which was a good thing, it was the free spirit thing, we didn’t have to worry about how many sales they were making. We could release whatever we wanted basically. It was paradise.

EB: Do you think being able to create whatever you wanted gave trance and the artists and labels behind it that sense of freedom a lot of people talk about?

RH: Yes, definitely. It was a lucky situation it could be this way, when you can be creative and work on whatever you want to, without taking care of sales. Actually, Sven was sometimes worried it got too successful, when one track off his first album, “L’Esperanza”, went into the charts he was really scared, he wanted to take it off the market and was like “ooh sellout!” haha.

EB: If we’re looking at trance now, from a cynical perspective, you could say it has sold out with how big and commercial it’s got. It didn’t sound like that was the intention at the time to make money out of it, it was just about the music.

RH: Exactly, every weekend we were in the club. Every weekend we heard new stuff from different music producers and we went to the studio on Monday or Tuesday, and used the inspiration we had been hearing in the clubs all weekend to help give us new ideas and we would try to recreate these sounds in the studio. It was all about this, literally only.

EB: What kind of clubs were you going to at this time that helped influence you in the studio?

RH: We had this lucky situation because Sven had his own club, the Omenin Frankfurt, that was the main thing. It was his home, his playground I guess. There was also the Dorian Gray in [Frankfurt] airport. So on Friday we would go to Omen, and sometimes we would have new tracks, and Sven would play them on the night to test them out. On Saturday we would go to Dorian Gray where DJ Dag would play, he was the resident DJ for the ‘famous’ Saturday night til Sunday noon time in the Dorian Gray club. So this was the ritual, these two days.

EB: Aside from being Sven Väth’s producer, you had another project on Eye Q as Earth Nation with Markus Deml. How did that materialise?

RH: Earth Nation was kind of special. Markus, he’s a guitar player, much more from the rock side. We knew him from Frankfurt from all different bands before. He was in L.A. studying at the GIT (Guitar Institute of Technology), kind of an acclaimed guitar university. He came back to Frankfurt and Matthias, who he was really close friends with, said to Marcus “you have to try something, this new techno trance kind of thing”, and he was really scared in the beginning but really open as well. We sat together in the studio and tried something out, and this is how Earth Nation started, bringing two very different sides of the music world together. At this time it was tricky because there was no mixture of electronic and guitars, it was quite experimental to do this.

Paul Schulte and Ralf Hildenbeutel performing live as Earth Nation

EB: You seemed to utilise the guitar quite avidly which made the project unique. It was quite an unusual thing to do, given the continuing popularity of samplers, synths and drum machines in the late 80s.

RH: It was very unusual. In the beginning for people in the electronic scene it was a bit weird and people didn’t really like it at first because you had this guitar. But then we started to put it live on stage and we set up a whole band with Markus, me, and a bass player. And there was the drummer, Paul, who played the electronic drums live so we had an old school band type of thing but with very modern sounds and techno elements. In these times when you had a live act from the electronic scene you usually had two guys with a DAT player and/or a sequencer raising their arms, but after a while people realised that what we were doing was quite cool and we started getting good feedback for this.

EB: Your music seemed to transcend beyond the club which is where a lot of people associate dance music to exist. Did you take Earth Nation outside of Frankfurt with your performances?

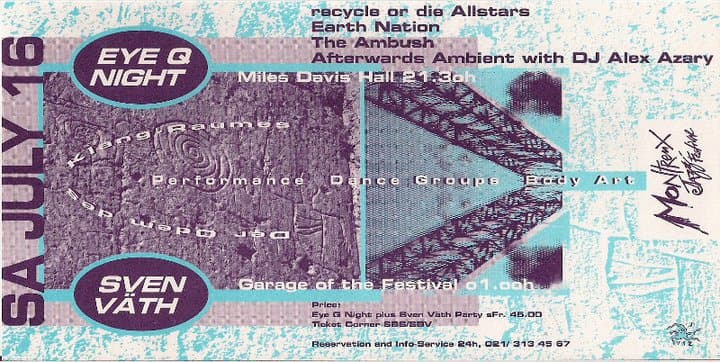

RH: Oh yeah. We had the lucky situation in 1994 where we played at Montreux Jazz Festival [Switzerland] and there was an electronic music stage. Claude Nobs, the guy who did Montreaux, was always very open with other directions. He invited us, there was an EYE Q electronic night, and this is actually where we had our first gig as Earth Nation.

From there on we had many gigs across Europe. In the UK we played at Tribal Gathering, Brixton Academy, Kristiansand Festival [Norway], Vision Festival (Switzerland), many techno club gigs over Europe. But also with the events, we pushed it further than what the crowd would usually expect because we were playing a sound that was danceable with a good electronic beat but also with guitar and other elements which made the performance come alive. With the time and the experiences from the live gigs we became more and more electro and techno-orientated, and eventually Markus (and a bit later the bass player, Oliver) left the project. So, it was the drummer, Paul, and me who continued Earth Nation, which was a very energetic combination.

EB: Was there a country or city who were more receptive to your act?

RH: It went really well in Germany. We had quite a lot of gigs in the UK. I think it went well here [in Germany] because I think people were a bit more open to experimental ideas. We had a very good audience base in Switzerland too.

EB: What about the scene in Goa? Eye Q and the music you were making was seen to be branded a little bit like Goa trance?

RH: It’s kind of funny how this developed because Sven at the time had a couple of years where he used to be a regular in Goa. He had a regular takeover in January/February for a couple of weeks. He also did DJ there then because they had huge parties. I don’t know, I never intended to make Goa trance but Earth Nation did have something that was very in line with the Goa scene. A couple of our 12 inches were very big in the Goa scene especially. I was there once too, so it all got a bit connected, even though there was never an intention to do Goa trance, it just happened somehow.

EB: What was the trip to Goa like and how was it different from European partying?

RH: It was a great experience these days, the crowd there, the typical ‘Goa people” were quite different and they had their own unique style. The parties always took place outside at some beautiful locations, til the sunrise and longer, so kind of a nature flash – sounds cheesy, but that’s how it was indeed. The music was a bit different to the style we were used to in Europe, the typical ‘Goa-style’ had its own elements, it was more trippy.

EB: I can’t work out whether Sven and the Eye Q crew introduced Goa trance to Goa, or whether it was the other way round?

RH: We didn’t introduce the Goa side, I think it was there already somewhat. Sven involved it a little bit in his sets, I think it just kind of happened. I also wouldn’t see Earth Nation as a core influence on the Goa sound. But we had similarities in the style for sure.

EB: Alienated is actually my favourite dance music record, the one with the “(Earth Mix)” on it.

RH: That particular mix was really popular in Goa actually. There were some really great productions from that scene, a label that springs to mind is Platypus, but 30 years ago I can’t remember what else.

EB: A lot of the sound in Goa was very focused on cosmic 303 and ethereal sounding vocals. This leads me onto the woman behind the vocals heard on your record Alienated, Corinne Cassiani-Ingoni. How did you come to collaborate with her on this record?

RH: On the album there was a guy doing some vocals, Herman Vieljans, he did this weird spoken half sung vocals. She was a good friend of his and he introduced us to her. She was more of a classically trained singer, but she was crazy enough to come all the way to Frankfurt and do these things. She was incredibly talented with a beautiful voice and she just stood in the recording studio and more or less improvised to the tracks. We took bits and pieces and put them together for the record and it just worked really well.

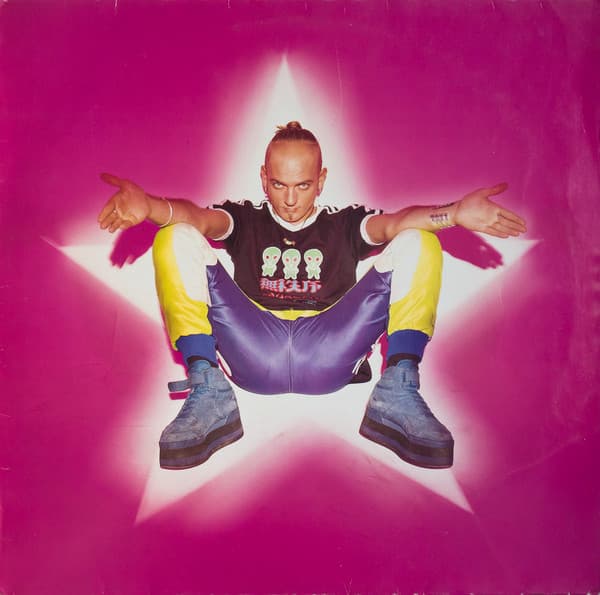

Ralf Hildenbeutel and Markus Deml in the studio

EB: A lot of the music you were co-producing under Eye Q Records had a richness to the sound that I personally feel not many electronic producers were creating at the time. Do you think trance music benefitted from these classical and instrumental foundations?

RH: Yes, I think so actually. With Sven, when we did the first albums, because he was also very open and we sometimes had a flute player for a track, a violin player mixed with the electronic sounds and samples … there were no limits really. Also, I think the EYE Q sound wasn’t really the ‘cool’ stuff in the scene (other than Harthouse), but it had a huge impact on its listeners for its emotional and touching aspects in the music. It contained a mixture of the beats and from the harmonic side the pads, and also the albums had some classical influences. So yes, it is probably because of that background.

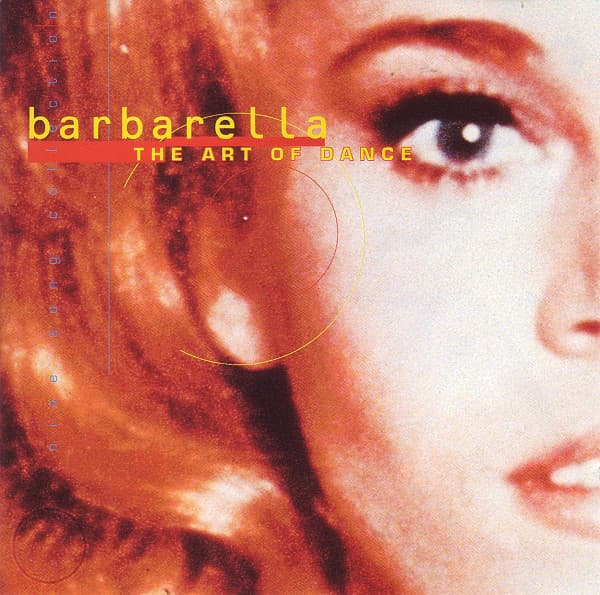

EB: Let’s talk about your musical relationship with Sven and your project Barbarella. Wasn’t this one of your first electronic projects?

RH: Barbarella was the first common project with Sven, the first stuff we worked on together. It started with a 12 inch, where one side was harder and the other was the more trance-y side. It developed into an album project and we released The Art of Dance_. We watched the cheesy cult movie_ Barbarella from 1968 with Jane Fonda and took samples out of it. The movie was the inspiration for the album. We had been fascinated by the fashion style in the movie, often the actors looked like the kids in the clubs. Then we started on his solo album, An Accident in Paradise_. Sven just got back from Goa where he made a bunch of field recordings which we used, basically we’d just write something out in the studio and it worked really well, there was a lot of chemistry._

EB: You seemed to have quite a lot of influence over Sven’s records?

RH: He had this open mind, he didn’t just show me a record and say “hey let’s do something like this” like a lot of DJs from the time would. He wouldn’t say can you show me this groove, show me this bass. Sven is not only from an electronic background, he listened to tons of different music back then and we both had this really open mind to bring it all together. The work was 50/50; he had always lots of ideas and I could really lift myself out and he could take everything from me and give me his influence to take the music in other directions.

EB: What was it like forming all these different trance projects with your friends?

RH: EYE Q in its peak released two, three or four releases a month. Other artists involved were Pascal Feo, who unfortunately passed away recently, Cosmic Baby, and many others. It was kind of a natural order to do a remix for an artist and they would do one in return. So we were always swapping mixes and stuff like this, that’s how I came to make the “(Porte De Bagnolet mix)” of “Cafe Del Mar” for Cosmic Baby [and Kid Paul as Energy 52]. You had so much output from all this inspiration you started to create pseudonyms for all these projects, I released under Icon, Progressive Attack, Odyssey of Noises, and others. Odyssey of Noises had actually been also used by Matthias, Stevie or Sven, like whoever had a track could use this project name.

EB: There seemed to be quite a community of you growing. Was Cosmic Baby from Frankfurt?

RH: He was from I think Berlin at this time. There had been this rivalry between Frankfurt and Berlin of which was more of the techno city. Was a bit more like this from outside the scene than inside our scene, so this is how we had our burning connection with Cosmic Baby.

EB: Was there a rivalry between Frankfurt and Berlin in the music scene?

RH: It was more of a media hype and a bit of fun. It was like which city is more the techno capital. But at the end of the day we had all been partying together so it wasn’t really a thing.

EB: Your trance projects seemed to fade out in line when trance took a cultural and musical turn. Do you have any thoughts about how the style developed in the late 90s?

RH: From 1991-96 … ’97 maximum, it had run it’s time I think. At a certain point for me everything was set, there were no new influences. Everything was done and then the new dance stuff came and the commercial trance, eurodance etc. So, I just quit it more or less. The same with Matthias and Stevie and this was also a time when we started to focus on new projects and musical challenges. It all became a bit cheesy and in the underground I didn’t find new inspiration, I myself didn’t know what to do any more. I remember the last Earth Nation album and it was really difficult. As a musician in general, you just need the inspiration to do something else. I respect finding producers that after years of producing they are still doing this kind of music and are really good at it, I couldn’t do it.

EB: Someone who springs to mind when you say that is Oliver Lieb. Did you have much involvement with him and the Harthouse roster?

RH: Funnily enough I knew him from very early times because he used to be a bass player. He used to do funk and Level 42-esque stuff in bands. Then years later he appeared at Harthouse and he was doing this crazy techno shit, I was really blown away. He had his studio on the same floor as us, but I have not seen him for a very long time.

EB: Seemed like it was a pretty close knit community, which has since grown into something so globalised. Did you have any idea this kind of thing would happen to the trance community?

RH: You could feel that it was new and different and it had a big power. But I didn’t know where it was going to lead to. The good thing is that when you are in your early 20s you don’t think about these kinds of things, you just do it. If you are lucky enough to get an opportunity like this you just accept the situation because you’re never going to know what will happen. Frankfurt is quite a small city. When you went to the centre there were two main clubs there and a few cafes and stuff and you all just hung out all the time and got to know everyone, that’s what made the scene so strong. In the early 90s you had two sides of the city, the bank side and the techno side. But in the late 90s clubs started to close, things just changed and I think it was a natural progression. Things change, and you can’t keep it going forever.

EB: Can you remember any stories from this time, perhaps from the club or the studio?

RH: It was a time when iPhones didn’t exist, so maybe it is a good thing that I don’t have any proof of what happened.

EB: It must’ve been such a different atmosphere when there was no digital communication.

RH: Today everything is immediately photographed or filmed and it just wasn’t there, you just lived the moment and listened to the music. Everybody wasn’t only focused on the DJ, taking pictures of them. People were going crazy, dancing and everybody was talking about the music, that was what was so fascinating.

EB: Do you think your involvement with Eye Q in the early years has influenced your composition working in film up to now?

RH: Very much so actually. I still have a strong connection to my classical education, in piano and neoclassical music. But the whole electronic thing in the early 90s still influences me today, I do music differently today because of this.

EB: That’s something worth cherishing I guess, not everyone has this opportunity.

RH: Definitely, I am so happy I could be there. It’s special to have it.

Featuring the music of both Hildenbeutel and Väth, listen to Biodegradable Soundsystem’s inaugural show:

Author

Eleanor Bickers is an electronic music enthusiast and writer based in London. She runs the Biodegradable Soundsystem series on Threads Radio, exploring the symbiosis of written, verbal, and sonic communication. In her spare time she often finds herself DJing, raving, and imagining alternate realities. You can find her on Instagram: @lnr_dj

Back to home.