Revisit Morley’s Techno Mecca The Orbit

Part of the Biodegradable Soundsystem series, Eleanor Bickers speaks to Jon Nuccle and Mike Humphries, stalwart residents and DJs of the famous yet elusive 90s techno club The Orbit, on their perspective of Leeds’ club culture.

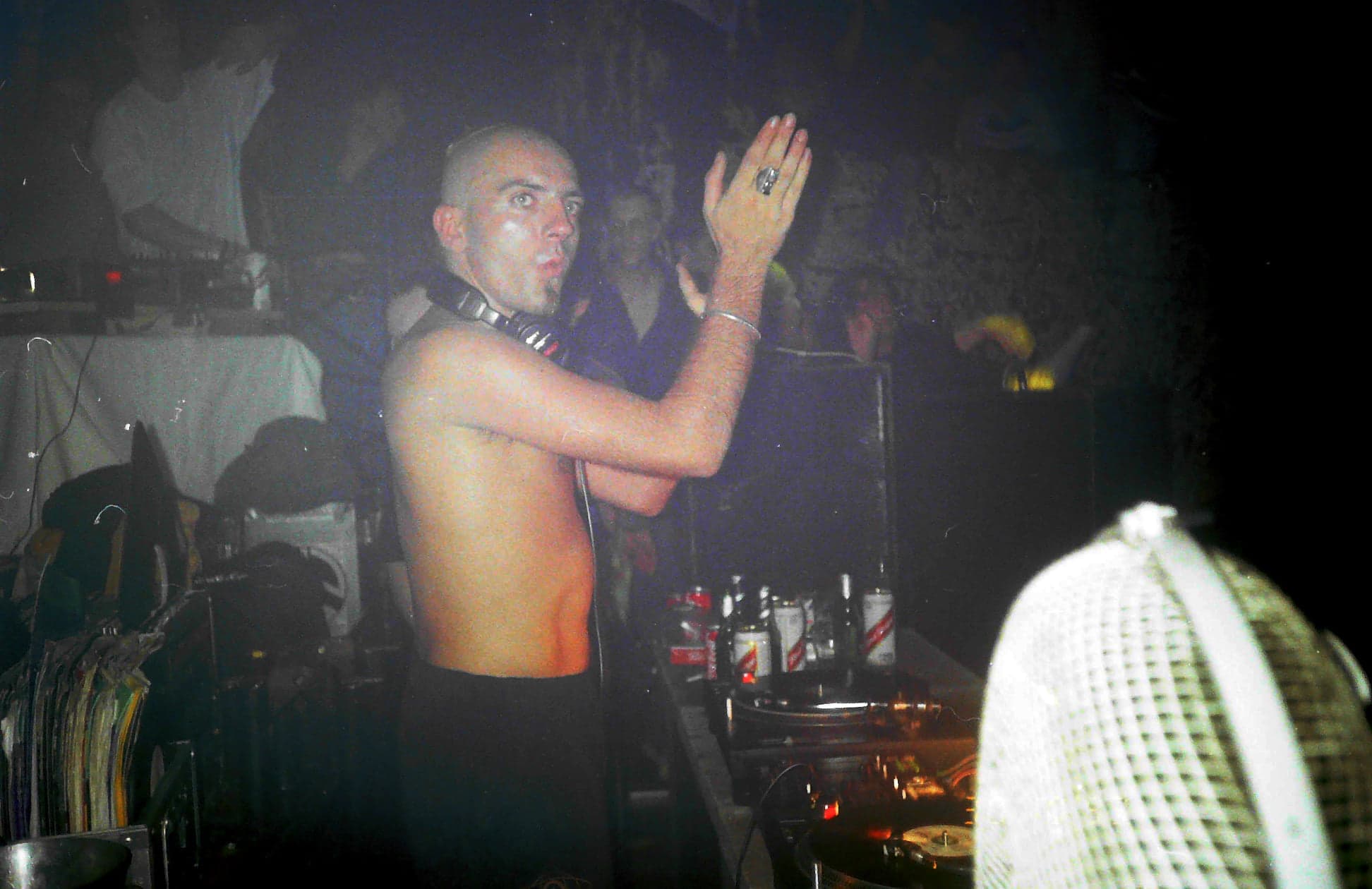

Sven Väth 3rd Birthday, The Orbit 1993 – Dave Royston

An orbit is a regular, repeating path that one object in space takes around another. The elliptical deleuze emulates the fragmented memories of a club night born in Ossett and made in Morley: spinning wax melted over the turntables from the perspiring ceiling, limbs swung from the curved three story balconies, and rotating fists clung to the ecstatic atmosphere. Magnetised to the spirit of the scene, perihelion punters soaked up their tea in the queue at half past 6, ‘take the biscuit’ flyer in hand waiting eagerly to get into the legendary club night The Orbit.

Run by Sean McInereny, Nick Gundill, Darren Turner, Neil Harston and Sean Kendrick (1991-2003 by Sean & Nick), the club night began in 1991 at Woburn House aka Thirtysomethings in Ossett which fed off the comedown of the rave scene’s golden era. Before long it was operating in tandem with The After Dark in Morley, an old Victorian picturehouse turned club. “Through The Orbit being there, Morley became a techno town and the culture seeped into the wider community” explained Mike Humphries, ex techno junkie and Orbit residential stalwart alongside DJ partner Jon Nuccle, who were musically involved with the party across ten years. Not only was it a local labour of love, it was seen as the UKs answer to Tresor, Berlin and often praised amongst artists, ravers and press as the best techno club in the world. But to Nick Gundill, founding member of The Orbit, “it just became what it was”, a club of its time built within the rotating mechanics of the rave wheel. Being pedestalled alongside legendary clubs and techno institutes wasn’t built into The Orbit’s DNA, often shying away from press coverage and maintaining a level of local integrity and international modesty, “we weren’t celebrity promoters, it wasn’t our bag”.

In light of the club’s 30th anniversary this year, this feature traces The Orbit’s history through the lens of DJs and in-house label residents Jon Nuccle and Mike Humphries, and promoter Nick Gundill, navigating the early years of Leeds’ dance scene up until the club curtailed into an Italian restaurant. The retrospect is a souvenir for all that came and went through Yorkshire’s techno mecca.

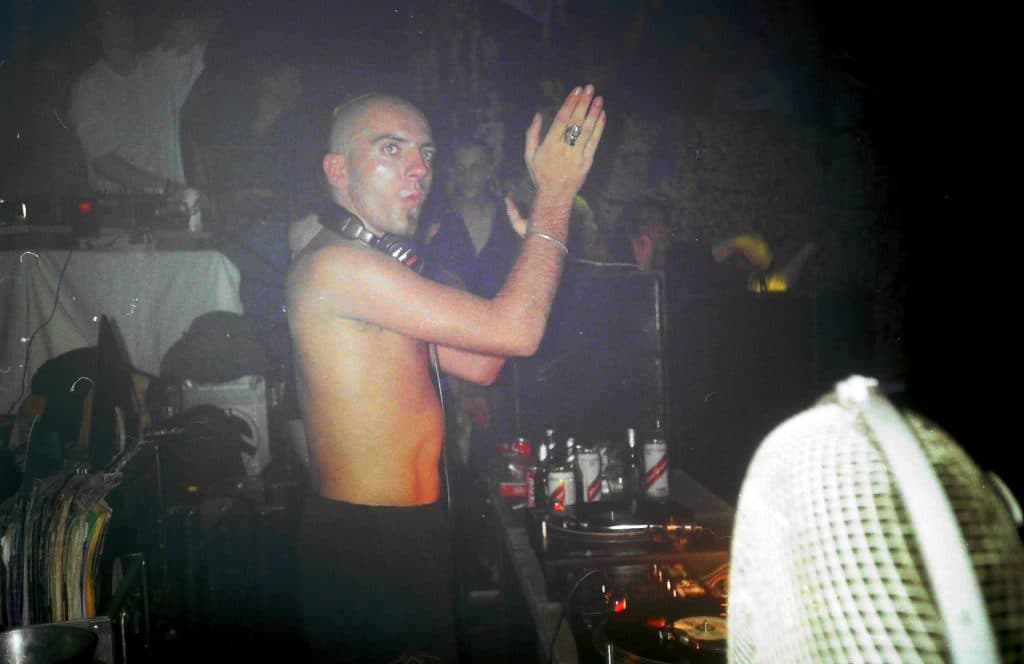

The Orbit’s success recipe remains a cryptic labyrinth of “a bit of history, a bit of luck and a lot of hard work”, described by Nick as “flying by the seat of your rave pants”. Some things are best left unturned, “it’s like asking artists why they paint a certain way, they can’t necessarily explain it, they just do what they do. Sometimes there isn’t really a deeper meaning, it’s nice to let people make their own mind up”. And in that sense, isn’t the success of something built upon the attitudes of those it serves anyway? That would give The Orbit a very universally accepted narrative: a techno club of the highest order putting the music at its pulse. With Leeds being a pioneering region of UK dance music, it’s no surprise The Orbit’s artist bookings sought out premium techno acts. Although it wasn’t the very first club night to propel rave forward. Perhaps Jon and Mike’s techno spear tackle into “Leeds 6” lay the frequency foundation for a more prepared crowd of party goers. ”They weren’t ready for us” claimed Jon about their music policy for Microdot, the first party in Leeds pushing a more reformed and purist sound of techno, leaving embers of the rave scene behind. “Musically Leeds at the time was great with pioneers like Unique 3 and LFO but by the time we started Microdot in ‘91, around the same time Orbit started, the club scene in Leeds was really poor for techno music, there was pretty much none. It was all piano rave and a little bit of hardcore”.

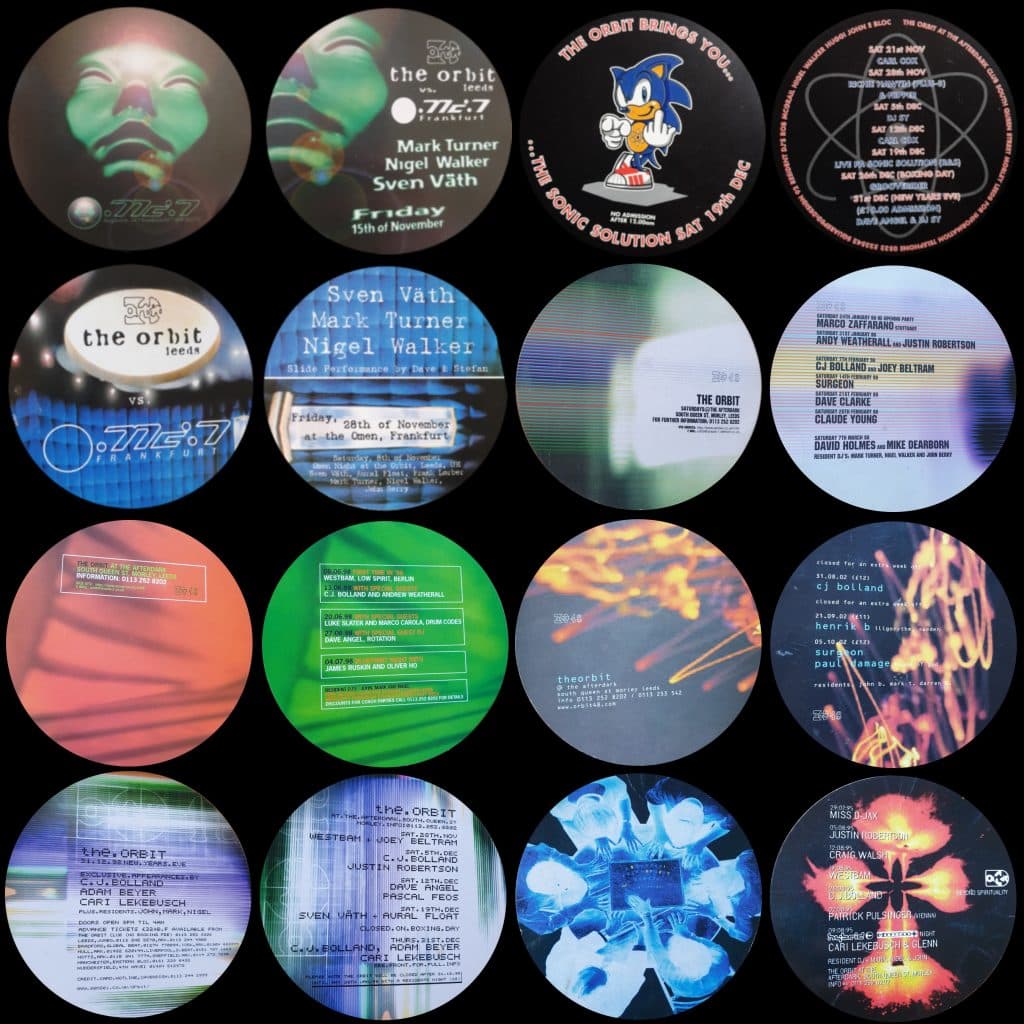

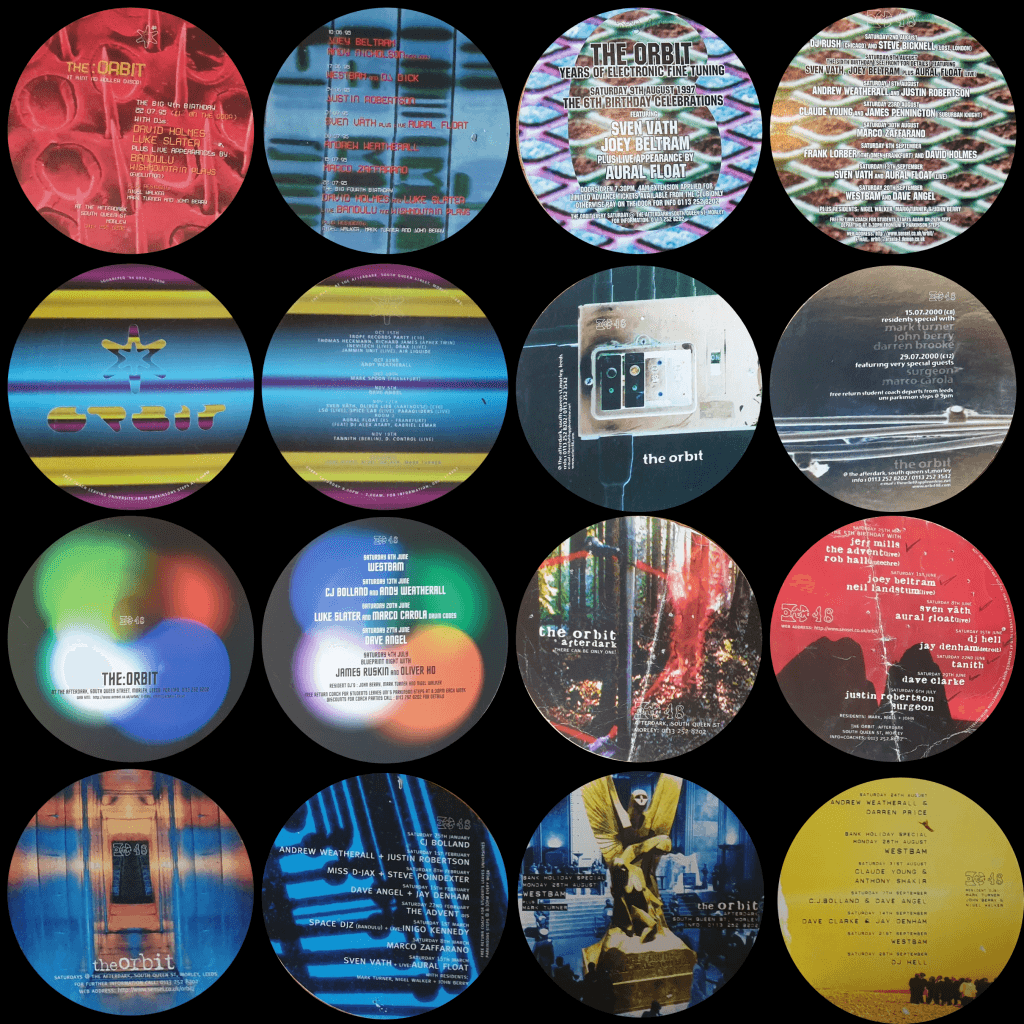

Flyer collection, Gaz Wright

But the club scene is not to be confused with Leeds’ entire party scene. The dub sirens of Chapeltown wailed around the beams of old Victorian terraced houses otherwise known as blues bars, devoted to dub reggae sound system culture, such as Nuccle and Humphries’ regular after-hours DJ slots at Sonny’s. “Originally they were playing all dub and reggae music – until the summer of love hit!”. Suddenly the blues were blurred between dub, acid house and hardcore. “You’d be DJing and have a dude standing next to you doing it old style throwing off echoes, effects and MCing. So there was still a hangover from the dub reggae scene – that’s how it influenced jungle later, that same thing was probably going on all over the country”. It was sound system culture that lent its hand to the first UK bleep & bass track, Unique 3’s “The Theme”, and put Chapeltown on the map as an audio-cultural catalyst.

With this in mind, the area had become a melting pot for a certain attitude towards underground music culture, harnessing a committed sonic architecture whose walls were already painted and lived in. “The venues in the centre of the city weren’t interested in putting on a techno night. We knew that we were safer with a particular culture in Chapeltown” explained Jon. But even this cultural safety net couldn’t stomach a purist techno policy. “Microdot had a strict music policy, it was techno only. That is what prompted us to start it, we couldn’t hear any techno anywhere and we didn’t know about The Orbit at the time” who were still stationed in Ossett championing the old skool piano rave sound, booking the likes of Grooverider and Sasha. It seems obvious to seek rave refuge in city centres, but the Trans-Penine Express allyship of dance destinations like Preston, Burnley and Bolton symbolised a working class cultivation of youth culture. “A lot of places along that corridor are all working class areas where people escaped from what was going on”, inferring the post Thaterchite disillusionment. “I think if we had run the night in the centre of Leeds we wouldn’t have had the longevity we did” explained Nick. “Being in Morley, it fought against the fact that it was in the middle of nowhere, the things that worked against it made it work”.

Jon thinks “The Orbit did it properly when they moved to techno. They did it very professionally, and that was the difference between them and Microdot. We were just a bunch of music fans trying to put a night on”, ruminating on the idea that it takes more than just a radical music taste to propel the success of an event. “Putting on techno nights was not an easy thing to do, we were very big fish in an increasingly small pond, we didn’t set out to do that, it’s just how it happened. We were a weekly techno night for over 1000 people, there weren’t so many doing it that often” Nick explained, echoing the weekly efforts of other institutes like House of God, Voodoo and Club U.K. “We didn’t want to do it in Leeds city centre because that’s where all the piss-head clubs were and the two types of nights didn’t sit well together. So you’d spend half your time turning people away because you know people wouldn’t enjoy themselves. Sometimes I’d take people upstairs without paying to show them the event and they didn’t realise what was gonna greet them at the top of the stairs, it wasn’t their idea of a relaxing night out whereas for other people it was their release from everything”. Operating a slick door policy was a vital component of The Orbit’s endurance, cultivating a crowd dedicated to a genre and culture of music that wasn’t universally accessible or appreciated, which subsequently made it what it was.

Credit: Gaz Wright

Jon and Mike’s Microdot efforts weren’t entirely in vain, as they brought over the first international techno artist to Leeds, booking Front 242s solo answer to techno, C.J. Bolland alongside Eurythmics remix warlock and all round techno legend Dave Angel (the good stuff, you know – before the sweet dreams tech house bro edits). When you think of C.J. Bolland you think about the pioneering impact he has had on the Belgian transatlantic techno lineage, but the ravers at Leeds’ well known club The Warehouse “didn’t know who the guy was behind the record…it was the time before producers became big DJs, it was still the faceless techno thing back then”. It wasn’t until 1993 “when thing’s stepped up for techno when The Orbit took it on full time”, who were “very picky about who they were booking”, ensuring only the best talent were at the controls such as the likes of C.J., Joey Beltram, Claude Young, Jeff Mills, Miss D. Jax, Gayle San, Underground Resistance, Richie Hawtin, Westbam, Hardfloor, Carl Cox, Steve Bicknell, Surgeon, Aphex Twin, Frank De Wulf, Adam Beyer, The Advent, Dave Angel, Sonic Solution and many more heroes of the 90s. With them came the stalwarts of The Orbit, the long standing residencies of Jon Berry, Nigel Walker and Mark Turner. “Very very very very very difficult to get booked in there” Mike Humphries pointed out, discussing The Orbit’s booking policy. As a local DJ it was no mean feat to earn your place in the techno mecca. “People would send their demo packs into clubs to try to get gigs. We had a studio on the top floor of The Orbit and one of the promoters came up and showed us what he had. He threw it on the floor, picked up a flight case and just dropped it on to the cassette..and then he picked up the pieces and left”.

Through the shattered archival polypropylene was a refraction of hope for those who could impress. The promoter’s would put the DJ on early doors and if they blew the roof off they’d be put on as a headliner. “It was that really old school way of if you can earn your way in they’ll take you on full time. Ben Sims is a classic example of that”. And that’s how Nuccle and Humphries bagged their first Orbit gig, via their Microdot slot on pirate radio Dream (99.9) FM. Not only that, it was a quid pro quo between them and the promoters of The Orbit, as the club would secure radio promotion for their night in return for interviewing a bunch of techno titans. “It was Dave Angel who got us on. He had a monthly residency when he could invite any guest he liked…we were called D.Kontrol back then”. But it was probably Hardloor’s last minute drop-out that gave the pair a gig to remember, warming up for the wizard Jeff Mills on The Orbit’s third birthday in 1994. Despite the standard being high, there was still an inherent DiY nature to the party and the scene at the time. “Could you imagine people clanging their beats now?” Jon mentioned, reminiscing the time they booked C.J. for Microdot and he showed up having never DJ’ed before, albeit an extremely talented and unique producer.

Flyer collection, Paul Gray

Flyer collection, Paul Gray

Flyer collection, Paul Gray

Flyer collection, Paul Gray

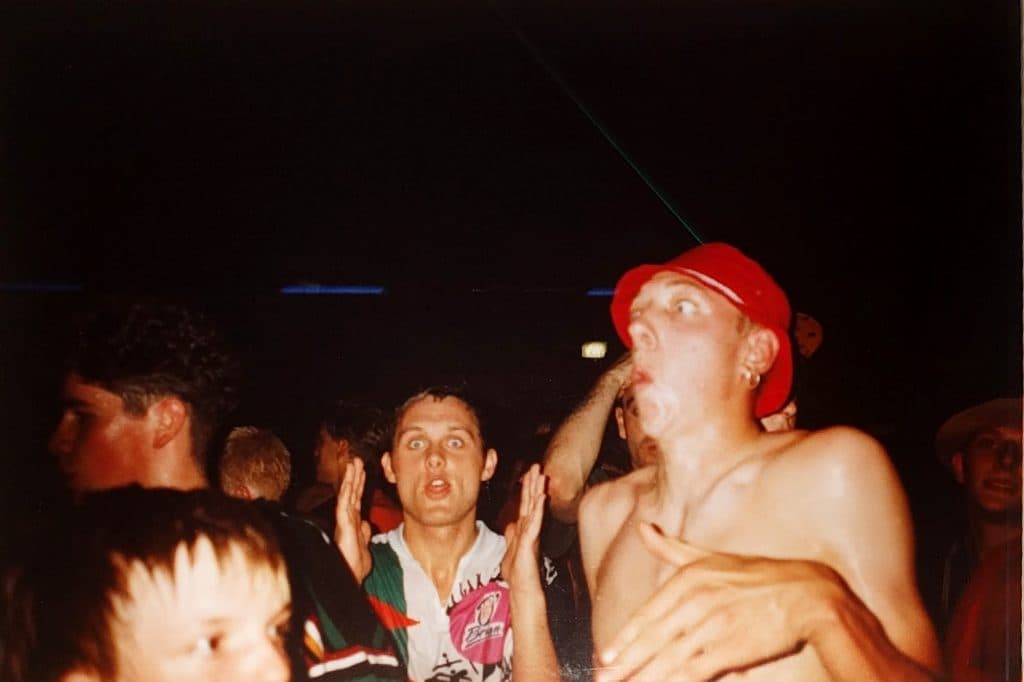

Really it is a given, you could get away with a lot more in the 90s – less scrutiny, more ecstasy. And it didn’t really matter, the DJ wasn’t initially the focal point of the club, tucked away in the corner leaving the ravers to their own devices, throwing shapes “north south east and west, not like they were attending church”. For this reason, DJs could have their own fun hidden away, which for a lot of them involved getting a bit west – “it was the spirit of the evening”, literally, tapping into the rockstar energy of the DJ psyche. You had Claude Young scratching the record with his elbow and his butt, Gez from LFO tried to play a slipmat (disclaimer: it might have actually been resident Nigel Walker), and the promoters pranked Mike by replacing his record bag with telephone directories before he went on stage. But it was “different strokes for different folks” as Jon took Jay Denham to prayer before his gig when he was booked to play. Whilst DJs evoked a kind of superstardom to fans, to the promoters they were just ordinary people. “We were never starstruck with the DJs” Nick clarified, “they were people I’d pick up from an airport, have food with them, get pissed with them, they were just normal people. I couldn’t even begin to tell you how many times I’ve been to Manchester airport”, removing the glamour and idolisation of DJ culture, a line of work so personal it became a string of friendships harnessed via a wider community.

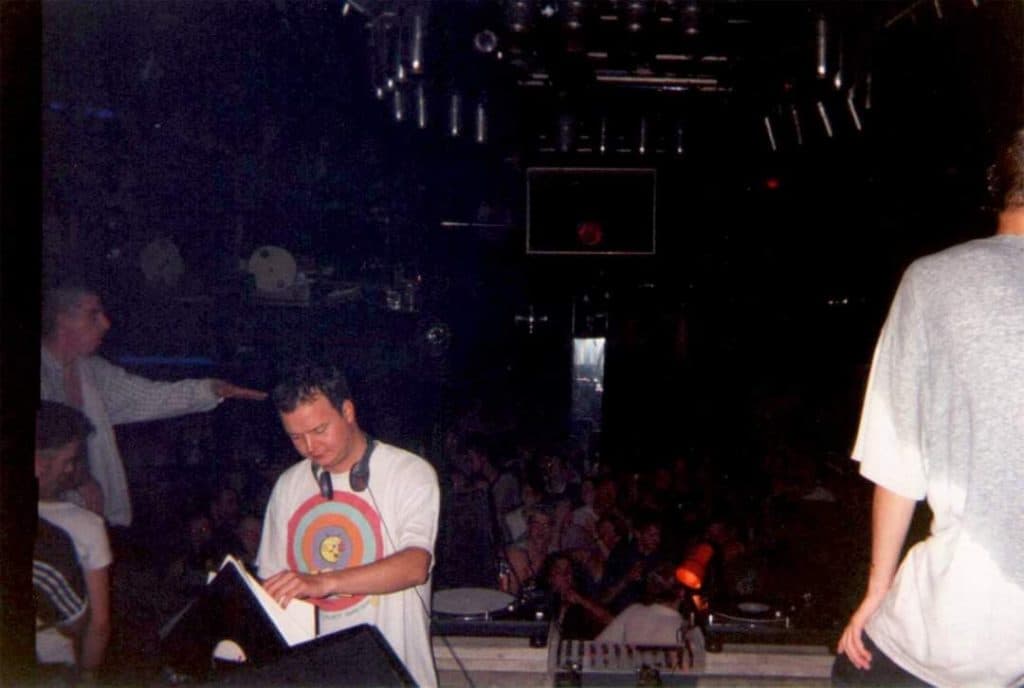

It wasn’t until 1993 when German megastar Sven Vath asked the promoter’s to move the decks into the centre of the dancefloor, a state of play which totally transformed the nature of the club; whether this was for better or for worse is in the eye of the beholder. “I bet years went by and people didn’t know where the DJ booth was” Jon illustrated, capturing the subcultural essence of the early techno community, a time before individualism existed in the club, where a genuine collective “enthusiasm” for music flourished. Despite this “[Sven Vath] really brought the DJ performance from backstage to centre stage” establishing a new dancefloor ideology coined as the Sven stare. “He could individually connect with people in the crowd and get them on his vibe completely. Nothing like that had actually happened before, when there was contact from the DJ to the crowd, almost on a personal level”. Across the pond however, DJs and producers who supposedly knew what they were doing were hunching over the decks of turntable wizard and 909 destroyer Jeff Mills completely mystified by his dexterity. “I watched him spin a record back and stop it on the beat and set it off again [on the correct beat]. To this day I’ve never seen anyone do it, not even hip hop scratch legends” mentioned Jon. This polar perspective shows just how versatile the 90s was (bearing in mind we’re talking about dance music versatility in the early to mid 90s, not 2021). “You had Sven Vath mixing seven minute trance records and then Jeff Mills turned up and just went – *whack* – this is fucking techno lads”, alluding towards his unconventional approach of beat chopping and juggling across three decks.

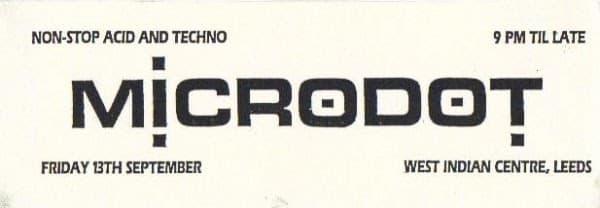

Credit: Paul Gray

So you had the raver’s DJ and the DJ’s DJ under one roof in the sleepy market town of Morley, a destination that shocked international artists upon arrival, wondering where on earth they were and how this place couldn’t possibly pull a crowd. “People were straddled on balconies thirty feet in the air” Jon recalled, a testament to the demented dancing performed by the punters. “There was a massive enthusiasm for the music from the audience, it was incredible. People used to be hanging over the DJs shoulder pretty much just to see what record they were playing” said Mike. Perhaps this provides a partial answer to The Orbit’s stellar reputation, a collectively calibrated frequency conducting energy between the artists, ravers and architecture. “There was a very large constitution of the same people going so everybody became friendly with each other, no one was kicking about being shady, there was a big family atmosphere. It was techno bringing people together”.

The fuse only blew when bongos were brought into the building, and what better place to bring a set of bongos to than the chillout room aka the Twilight zone, which is an analogy of all the slightly off kilter antics that go down in ambient rooms across the club and festival circuit. Mike recalls his bongo baptise – “remember that time I was sitting in the Twilight trying to get a minute or two’s respite and that kid was sitting next to me playing the bongos. The head bouncer came over to me and said ‘Mikey you alright? And I said to him ‘…can you ask that kid to stop playing them bongos?’ and he got his big torch out and said ‘You! Stop playing them bongos!’ and then he went ‘is that better for you lad?’..’perfect mate thanks’. This was followed swiftly by Jon continuing the bongo saga “oh yeah on the main dancefloor right in front of the speakers this lad comes on banging these bongos right next to us and this other lad leans over, Richard I think his name was, and goes ‘yo, fucking stop playing those fucking bongos or I’ll stick ‘em up your arse you c*nt…now…fuck off!’ So you get the impression really, people were pretty blunt at The Orbit, it was a very working class crowd, but overall really friendly”. Even leftfieldness on stage wasn’t always embraced with open arms. A bottle was thrown at DMX Crew and ravers turned their nose up at Aphex Twin, but surprisingly Wishmountain went off, the former musique concrete alias of Matthew Herbert who made tracks out of asthma inhaler puffs and cheese graters: there must’ve been something chipping away at people’s brain cells that night.

Credit: Gaz Wright

You could say The Orbit’s attendees were unique in their commitment to the music, but this also blossomed in a time when everyone was committed to rave. Putting your ego at the forefront of your lifestyle choices didn’t even exist until the DJ superstardom and global cogs of commercialisation infected the DiY circuit. Before the commercial curtain came down, dance music mirrored the same DiY attitude the punk scene cultivated, which follows the ideology of “being able to exist outside the mainstream music industry”. This reality typically existed via the exchange of DATs in the carparks of marquee raves. “Back in the day a new mixtape was like gold dust…1991 was when the big marquee raves were going on, and you’d be in the car park afterwards with all these muntered ravers and you’d swap mixtapes with total strangers ‘cos you knew what they were listening to in the car. So you’d end up going home with some random DJs mixtape from Norwich or something, and suddenly some guy in Norwich was now a legend amongst a group of twelve people in Leeds…punk rock as fuck man!”. Not only did you swap tapes, many were flogged at parties to support the underground DJs and promoters who weren’t propped up by industry money. This is exactly what Nuccle did at Microdot and then later on at The Orbit. “You’d have to go to the university and bullshit to them that you were a student so you could print off colour copies of the tape cover. You’d sell them in a few local shops in Leeds, and that would pay for the records that got on that mixtape in the first place”.

From bootlegging tapes later came the inauguration of The Orbit’s in-house record label set up by Jon Nuccle and club residents Mark Turner (of Eastern Bloc Records), Pete Simpson and Richard Wilkinson. “A shared studio was used as an opportunity to create something brand new. We pitched in money, made the first 12” and then we drove round London and pimped the records out. Eventually we got a deal with distributor Intergroove Records”. Formerly Radius (1997-98), the new label was called Player, which remained disconnected from the club itself as the promoters were “keen not to exploit its name” which worked out for Jon and Mike because they “liked the idea of it going back to old school faceless techno…from there you can do things as a collective and the end result is better than the sum of its parts”. The stature of Player, which could survive without the direct support of the club, led to Jon and Mike’s monthly residency in 2000, who had played previously under the alias’ of D.Kontrol, Area 51, Cold Dust, D.O.M, Pitch Invasion. and their own names.

Credit: Simon Young

Their live sets were an integral part of the duo’s Orbit journey, playing alongside legends like Jeff Mills and Dave Angel. “We had this shitty little sampler called the Cheetah SH-16, it had such short sample memory, about 8 seconds, so halfway through the set you’d have to play a DAT tape whilst you loaded up the samples for the second half of the set”. The Cheetah, alongside the Roland 303, 909, SH-09, DX11 and Korg Mono-Poly synth were amongst bits of kit taken apart from their studio, first in their basement flat and eventually above The Orbit’s dancefloor. The pair used whatever method they could to get their hands on drum machines, synths and samplers, although one time they bought some cheap kit from a local lad and when punk band member Mick Brown from The Mission turned up at their house he remarked “that’s my fucking drum machine, where’d you get that from? And that’s my mixer!”, which to their realisation had actually been stolen a few days ago from Mick Brown’s studio, something that was apparently pretty commonplace in the Leeds 6 area.

“Techno’s a funny thing, each part of the country has its own approach”, said Jon, describing the free party scene of Wales and the west country, to the barmy ravers of Edinburgh and Glasgow who “you wouldn’t want to mess with”. Back in Morley, due to it being a residential area The Orbit didn’t have a late licence so the club opened its doors from 7pm to 2am. “There’d be people hanging off the balconies at quarter past seven, people had only just had their tea”, which was a sight to behold as a bunch of teens and twenty somethings spilled out down the street. In fact, it ran so early that Jon found himself one time bringing his portable shaver to shave his beard in the queue because he didn’t have time to get ready at home. “What’s ya name, where ya from, what’ve ya had, why’ve you got half a beard?”.

Credit: Gaz Wright

So what do you do with over a thousand ravers at 2am? One of the clubs most difficult jobs was making sure the ravers left the premises swiftly after close. “We were in a very residential area so the [community] wasn’t used to seeing so many young people wide eyed leaving the building. We’ve had situations where residents have stood outside with a decibel meter to try and report us to the council”. In a sleepy town the Morley crowd needed another watering hole to hydrate their thirst for high octane dance music. For this you had to travel into Leeds city centre, such as the Chapeltown blues or an afters called Code which was situated in an industrial estate, a party Mike Humphries was a resident at describing it as “one of those places when there was only one toilet, opened at about 1am and would go on until people had gone home”.

The spectacle however, was the handful of official after parties The Orbit hosted in 1994 at Bretton Hall’s Yorkshire Sculpture Park, an experience like no other. “When you’ve been out to the club and you’ve done the full distance already completely bollocksed and you end up somewhere like that it’s..really weird”. Psyching out to Sven Vath with colossal Henry Moore sculptures sounds like the correct chemical equation to open the fifth dimension. But all good things must come to an end, as Nick mentioned he had to stop the Bretton Hall parties because the building was falling apart from the sound they were putting in there. This was a common problem for the techno scene as finding a building that complimented the progressive engineering of bass heavy records became increasingly difficult.

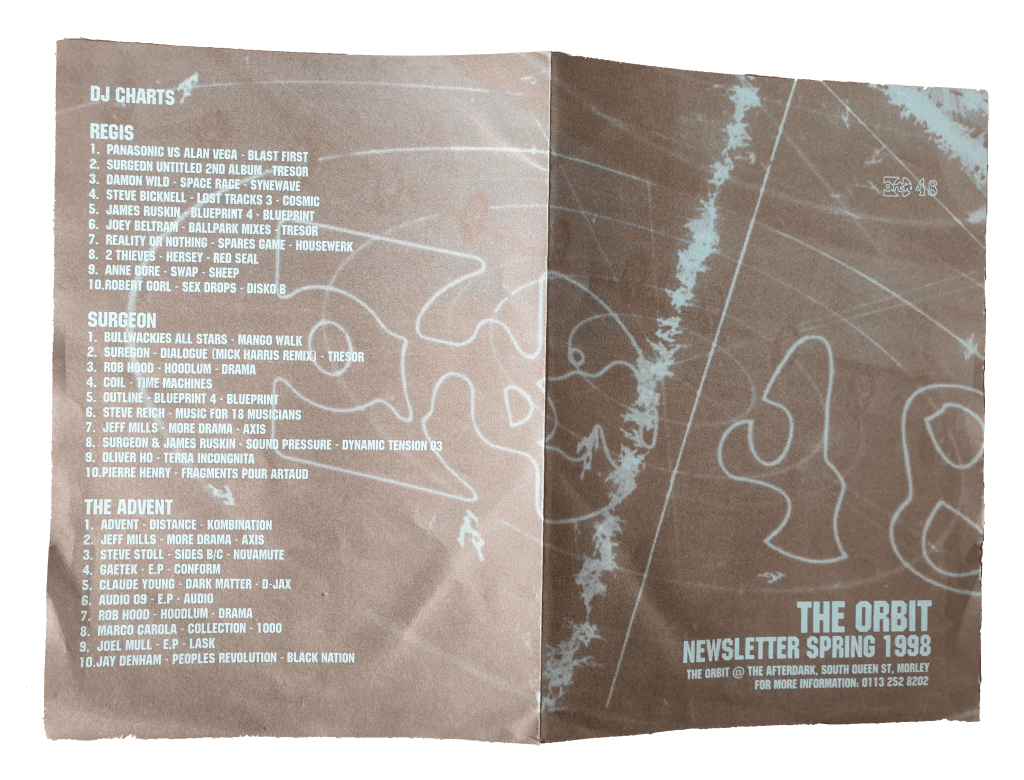

Ephemera – Paul Gray

The Orbit’s fate in 2003 was a seemingly natural progression to close and move on. “When we started we were big fish in a small pond, but by the end we were big fish in a diluted pond, at one point we were running every week with other nights on but eventually we were the only night running fortnightly so everything was on our shoulders and it was too costly”. By 2003, Nick had seen it all, from the decibel meter demonisers to the end of the night clear up when he once had to drag a passed out raver out of the sub bass bin. The history of The Orbit can never be told in one story, for it has thousands of unique narratives from its promoters, ravers, DJs, staff, engineers and Morley residents. “Everyone has a release that is culturally and emotionally distinctive to them” which was often misunderstood by those not immersed in club culture, but in a sense this has made those moments even more valuable to cherish.

Ephemera – Gaz Wright

The building which is known as the New Pavilion is part of Morley’s heritage, first a picturehouse, then bingo hall, club, Italian restaurant, and now boarded up ready to be sold for demolition by the council. A petition circulated last year which subsequently granted the building recognition as a cultural space from Morley Council. The future of the techno landmark is still unclear, but its legacy lives on. “When we started it we expected it to be one night, a big party with a few mates and have a good time, but it turned out more successful than that so it ended up being something I devoted myself to”.

Author

Eleanor Bickers is an electronic music enthusiast and writer based in London. She runs the Biodegradable Soundsystem series on Threads Radio, exploring the symbiosis of written, verbal, and sonic communication. In her spare time she often finds herself DJing, raving, and imagining alternate realities. You can find her on Instagram: @lnr_dj

Back to home.