REVIEW: The Last Angel of History – A Translation of Afrofuturism

“Threads’ very own Edward George pairs with the visionary filmmaker John Akomfrah to deliver a comprehensive and visually kaleidoscopic documentary centred on Afrofuturism.” by Alec Jetha

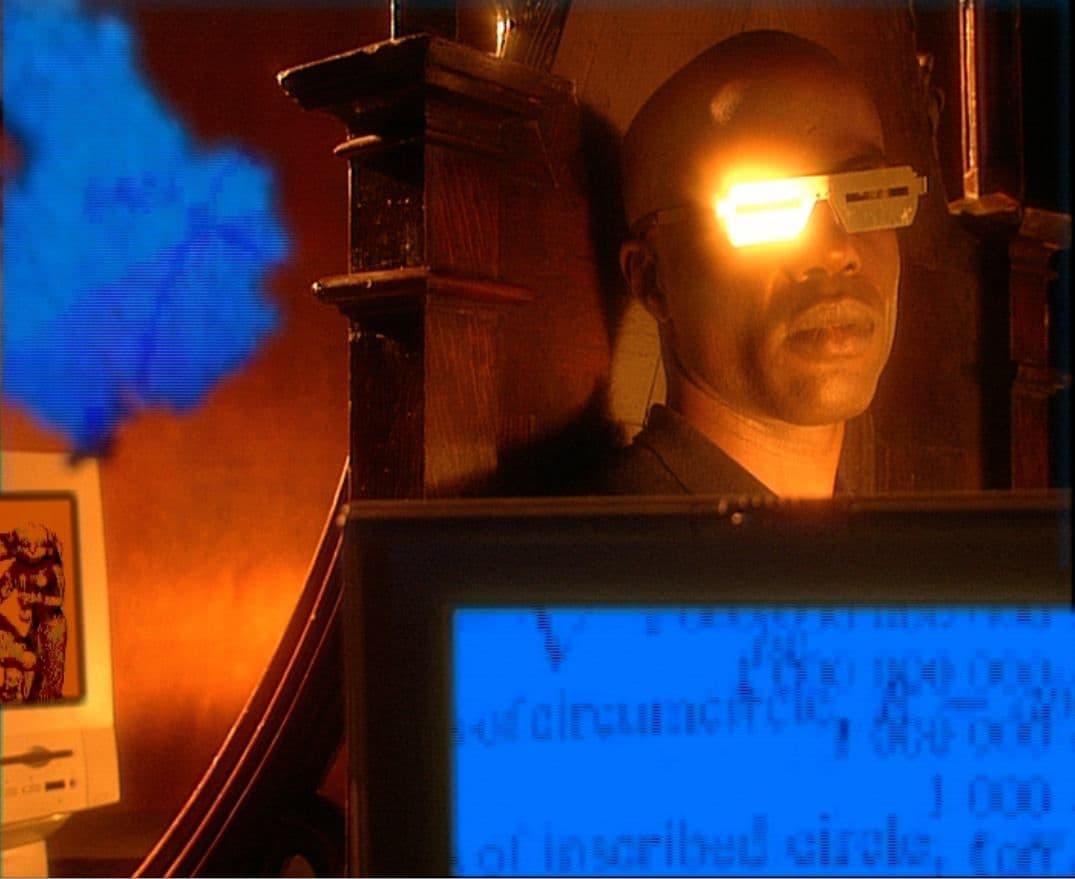

The documentary, The Last Angel of History, opens with a dispassionate monologue delivered by the narrator (and writer) Edward George. He recounts the Faustian-like tale of blues pioneer Robert Johnson selling his soul at the crossroads. Originally, the legend states that Johnson sold his soul to the devil to receive extraordinary guitar-playing abilities, allowing him to construct what we know as ‘the blues.’ However, here we obtain a slightly alternative take on the tale; instead, Johnson’s discovery—the blues—is described as a ‘secret black technology.’ This technology’s importance is then demonstrated by its influential nature—in other words, being responsible for the genesis of such pivotal genres as Jazz, Soul, RnB and Hip-Hop. This story then jumps to the future and introduces the ‘data thief,’ a character (also played by George) who features as the documentary’s protagonist. Similar to Johnson, the data thief is also searching for this black technology. However, this popular music mythology takes on a science-fictionised form: the legend states he must travel to the past to these crossroads to unlock the future. His clue to obtaining his goal is one phrase popularised by funk icon George Clinton, ‘the mothership connection.’

What George, Akomfrah and the rest of the creators demonstrate so brilliantly in this opening and throughout is a unique, vibrant engagement with Afrofuturist expression. The concept of Afrofuturism, coined in 1994 by Mark Dery, builds a relationship between technology and the African Diaspora. It reconstructs, disrupts and alters narratives and time; it communicates black experiences through science fiction and other artistic, intellectual and fictional imaginings. The fictional elements often function as metaphorical means of communicating these experiences, such as Sun Ra’s extraterrestrial heritage or the deep sea dwellings of Drexciya. The data thief and his mythology is a riff on these fictional tropes of Afrofuturism. Throughout the documentary, the data thief travels through time and collates information from interviews with the integral figures associated with and responsible for the cultural foundations of Afrofuturism. By including a fictional narrative, the documentary’s creators purposefully obscure the lines between fiction and reality, which plays a vital role in the documentary’s narrative.

This double axis of fiction and reality provides insight into Afrofuturism’s abstract, theoretical underpinnings while providing a lens into its evolution as an artistic movement. On one side of the axis, the audience is fed information about the seminal musicians and writers that propelled Afrofuturism and the development of its cultural, theoretical and artistic progression through interviews with artists such as Juan Atkins, A Guy Called Gerald, and George Clinton — as well as associated writers and critics, including the likes of Octavia Butler, Samuel R. Delaney, Kodwo Eshun. Even influential individuals outside of the immediate sonic/theoretical spheres such as astronaut Dr Bernard A. Harris Jr. and actress Nichelle Nichols are considered. The interview questions were scripted via a plethora of prior material that George, the research team and the director John Akomfrah collated. As George states, the basis of this material was :

"...citations and historical, literary, technological, photographic and phonographic connections between and across the margins of black culture."

Feeding these scripted questions, which are steeped in this significant subtext, to an eclectic group of influential individuals results in incisive dialogue, which paints a comprehensive cultural-theoretical picture of Afrofuturism. The ordering and progression of the interviews play out more like a discourse among thinkers and artists; rather than the limited interaction between audience and subject. Jumping between interviews, we hear the artists’ indirect (and direct) responses. When heard in tandem, these fragments seem almost dialectical, with the intertwining influences between artists’ on full display.

On the other side comes the underlying fictional and narrative components, the moments between the discourse amongst the interviewees: the data thief’s journey. While the data thief’s journey feeds the viewer an engaging sense of progression and conceptual contextualisation, its purpose is more extensive. This metaphysical journey is the vehicle which George uses to express his philosophical ideas on Afrofuturism. The script reveals more brimming under the surface than just an imaginative portrayal of Afrofuturism. One only has to look at George’s writings on the documentary’s creation to understand these intentions. For instance, the reasoning behind the documentary, George states,

"...was to affirm and cohere the ideas, practices, practitioners, technologies, artefacts and historical resonances of black cultural and political esoterica, which constitute the marginalia of black cultural expression, while also being a disquisition on futurity, loss and the aftermath of the Ghana revolution."

It’s in the narrative where the affirmation of these ideas and historical resonances take place. We see the data thief travel through the past and present. The past (or “the old world”) is centred on Africa, focusing on Ghana. The use of tenses here is inherently related to the play on time and narrative, which is central to Afrofuturism. Africa, specifically Ghana, is a temporal origin and reference point for these cultural and artistic developments due to its historical significance as a site of indigenous trafficking. So, in other words, George uses Ghana to trace back the genealogy of ‘futurity and loss’ that emanates within Afrofuturist expression. The play on past and future demonstrates this while keeping within the fictional aesthetics of Afrofuturism. There are further instances of these demonstrations in the narrative; for example, the prior mentioned relocating of the crossroads from 1930s-type folklore to a futuristic setting with futurist terminology such as ‘techno-fossils’ being used. Or the incorporation of George Clinton’s phrase ‘the mothership connection’ and its crucial role in the narrative.

Alongside this incredibly dense body of writing comes Akomfrah’s other brilliant contributions; his archives of footage and colourful frames provide a perfect graphical accompaniment. Akomfrah’s design further helps to drive the aesthetic of the film through iconography and visual motifs. The aesthetical configuration establishes a firm sense of style within the context of the genre. His direction of the documentary also drives engagement. The snappy composition of the filmmaking flows effortlessly, allowing a viewing that not only stands as excellent commentary but is also thoroughly entertaining.

As a sum of its parts, The Last Angel of History is insightful, dazzling and complex. It’s a complete, sweeping engagement with the Afrofuturist movement and its expressions, leaving no stone unturned. It not only translates these ideas expressively but actively engages and provokes discussion. While the esoteric subtext within the writing can be occasionally enigmatic, with the creators citing everything from post-structuralist philosophy to the fictional works of Delany, it’s also an incredibly accessible entry point into understanding the imaginative principles that guided—amongst other phenomena—the likes of Sun Ra and the birth of Techno.

Back to home.