Tony Davis: Life Before Digital, Integral Rebellion, and the Spirit of the Nineties Rave Scene

After a brief hiatus, Eleanor Bickers’ Biodegradable Soundsystem returns with an extensive feature on 90s rave photographer Tony Davis.

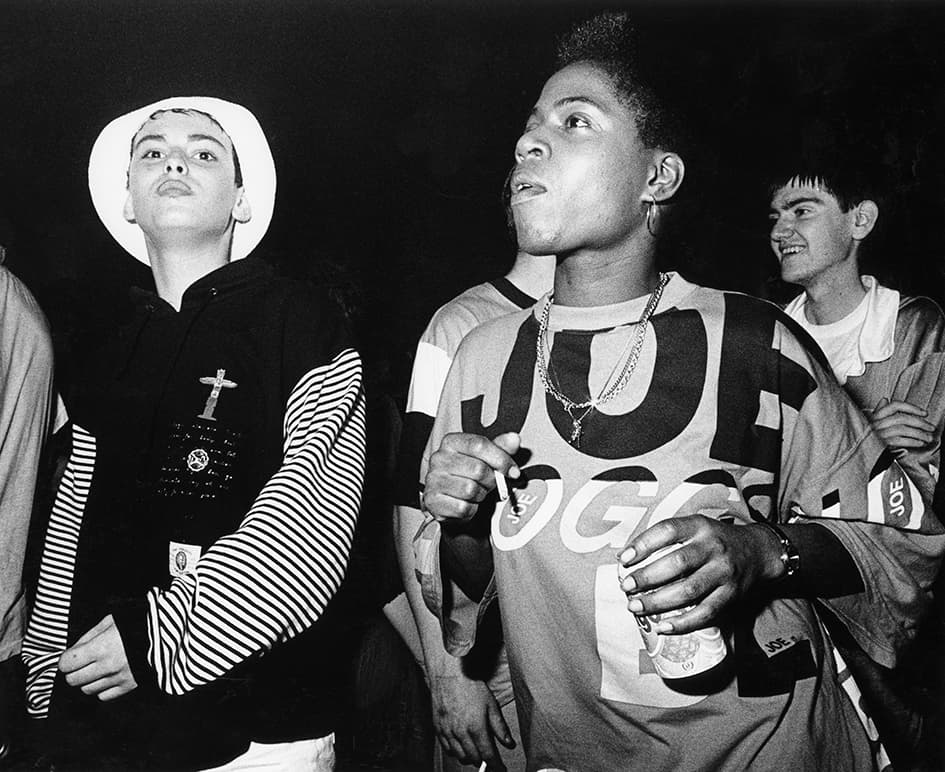

Eclipse, Coventry 1991

It was late on a Wednesday evening when Tony Davis and myself managed to get on the line to one another, a call I presumed to be an “initial chat” as he had requested but was unsure he had the right kind of information I was looking for. Despite his apprehension, I wasn’t interested in a summary of the entire acid house and rave scene of ‘88 to ‘94, rather I had become inquisitive about the many rave auras depicted in Tony’s 35mm film shots from ‘89 – ‘91 that he has been regularly posting on his Instagram page since 2019.

His work spans around fifteen years, which focused mainly on documenting football terrace culture and youth culture movements. Tony grew up on Nottingham’s Clifton Estate, which is where his interest in photography began around ‘89, documenting the club scene at Venus, Koolkat, as well as the raves run by the free party collective DiY Sound System: Rhythm Collision and Datura. After around ninety minutes on the line, I realised that my scrawled notes were all I had to whip up a coherent story about a particular dimension of Tony’s career as a photographer; documenting the hedonistic ravers of the acid house era, or as some like to call it: ‘the golden years’. This was no place for a Zoom chat with prescribed transcription, as Tony is self-proclaimed “a bit old school”. Naturally, for a twenty-something who has lost a few brain cells over the years and leans on the support of technology, the panic set in slightly, but his story flowed effortlessly and authentically. An individual who humbly identifies himself as a mere observer of the late eighties and nineties UK rave scene, had much to say that encapsulated its true essence. It’s lucky he was able to capture these rare documented moments of escapism, given that the ravers were all “off their nut”. Paired with his charismatic film archive, the following narrative is an account of Tony Davis’ vision of sound.

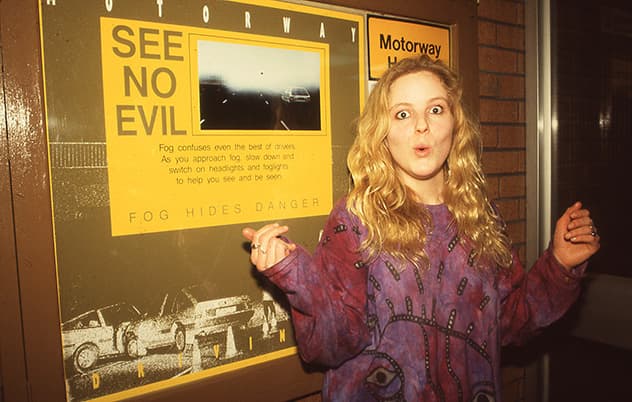

Sandbach services post Shelley’s, 1991

Rhythm Collision 2, Nottingham, 1990

Tony described his involvement in the rave scene as being “an observer rather than a participant”, and preferred to keep his documentation local to Nottingham and the surrounding Midlands, rather than the famous raves around the M25 and nights at the Haçienda. Despite this self-regarded title and being several years older than the ravers, they saw him as “one of them”. Drifting by the outskirts of the rave scene were met with stories that can actually be remembered, like when his girlfriend at the time brought back two Aussie friends from a free party “somewhere up near Derbyshire” to stay at her mum’s. They stayed in her caravan in the backyard and came out “absolutely flying off their first pill, totally off their nut” and wondered “what on earth [she’d] done to ‘em?!”.

Whilst the free rave parties of the early nineties sparked some of the most historic UK counter-culture controversy and have become almost biblical to the representation of UK dance music, Tony’s passion for documentation lay within the sweat dripping walls of the clubs. Some were a frequent visit, like Venus and Koolkat in Nottingham, but others were stumbled upon, like the legendary Eclipse night in Coventry. “It was such a wicked, dingy spot that. . . and everyone was on a different planet gurning their tits off”. Tony developed a niche, capturing ravers up close and personal, foregrounding the intensity of their enchanted expressions. As a viewer, you can relate to the sincere grins, gurns and gusto found in the corners of the clubs, elevating a sense of nostalgia and connection – “not a straight face in sight”. He mentioned he’s “only been to Coventry three times to see Derby play in the 70s 0-0 FA Cup, to meet the Dalai Lama, and this Eclipse night”.

Eclipse, Coventry, 1991.

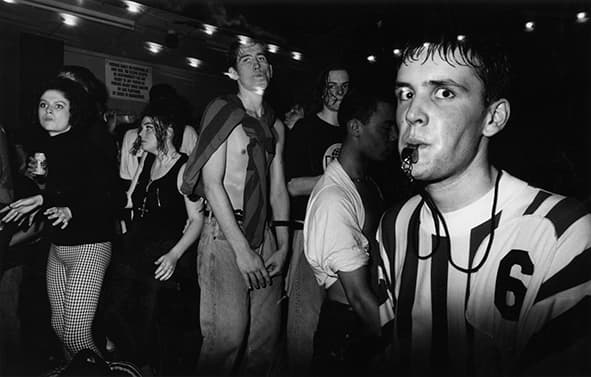

‘Wide awake club’ – Eclipse, Coventry, 1991

‘Wide awake club’ – Eclipse, Coventry, 1991

Perhaps his most frequent club visit was at Venus in Nottingham, a club owned by James Bailie, a name widely known within the 0115 dance music community. In fact his legacy has taken him right up to the present day, where he opened Stealth, now one of the most well known student clubs. Venus has housed some of the most popular DJs and artists of the time, such as Laurent Garnier, Norman Jay and Rozalla. Tony described his first encounters with Bailie. “Venus was basically the Haçienda of The Midlands. I queued up for the first few times, then asked [Bailie] if I could shoot his nights. He let me in every weekend I came to shoot, got his club in Mixmag, Face and i-D. I got a bit cheeky one time and started going in without my camera, he didn’t let me in after that which was fair enough really. These days he’s desperate for my prints!”. This sentiment solidifies the way Bailie and Davis lent on each other; a club so legendary but without the publicity it deserved; Tony visualised the euphoric atmosphere of Venus, providing a media manifesto for this hidden gem.

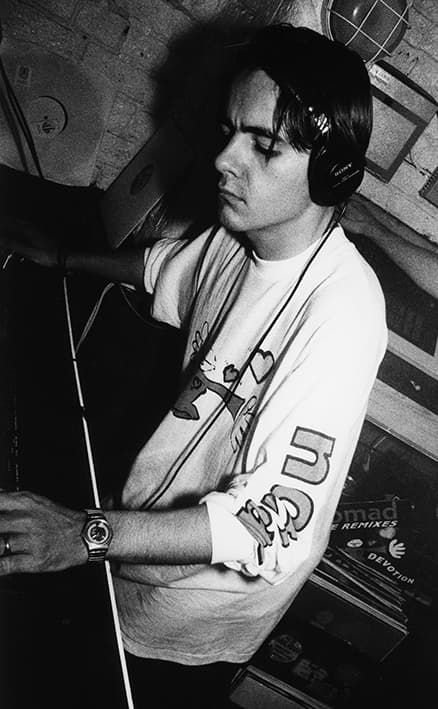

Another widely known collective of the nineties rave scene were DiY Sound System, a rave crew that bridged the gap between counter-cultural free parties and legal club nights. Tony travelled with DiY sometimes after going to some of their nights like Datura and Rhythm Collision, “I blagged it in really, turned up with my camera”. Thereon he went to Stoke services and Ibiza, a particularly contrasting phenomenon. “The main guys were Pete, Ricky and Harry. Simon DK (Harry) was the main room DJ, he was proper hardcore, y’know what I mean. Digs (Ricky) and Woosh (Pete) tended to be the ‘room two’ guys, and they explored many different kinds of music, it was ace”. DiY made enough money from their nights to carry on producing, recording and partying, cooped up in Squaredance Studio above Victoria Centre. He described the story of when a couple of mates, Baz and Matt, who grew up with Jason Williamson from Sleaford Mods took him to Venus – “that nails the DiY prodigy”.

‘Everybody’s free’ – Rozalla at Venus, Nottingham, 1991

‘Salvation in no one else’ – Venus crew for Mixmag with Nottingham’s number 1 bible basher, Nottingham, 1991

Laurent Garnier at Venus, Nottingham, 1991

Something unique about Tony’s documentation is his ability to go beyond the dancefloor, elevated by his time spent at Sandbach services after a long night at Shelley’s Laserdome in Stoke. The convoy has become known as one of the most iconic rave rituals, having developed from prior youth culture movements like the hippie and punk scenes in the 60s and 70s. It wasn’t unusual for ravers to travel far to reach their favourite stomping ground, symbolic of a motorised pilgrimage. The Sandbach service station stop, much like many others up and down the country, were an extension of the night out itself, much like an after party. “The service station, where the weekend never ended”, a comment from an original raver on Tony’s Instagram. The two girls that appear in the Sandbach photos stand alongside the advertised messaging, “see no evil” and “take it for all the right reasons”, which endeavours a comparative innocence that can be acquainted with the youth culture movement.

‘Take it for all the right reasons’ – Sandbach services post Shelley’s, 1991

‘See no evil’ – Sandbach services post Shelley’s, 1991

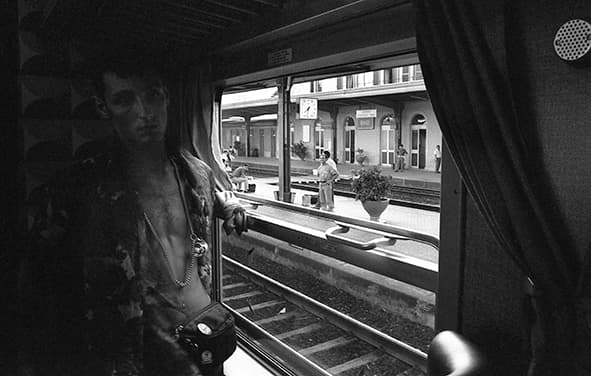

Tony visited Ibiza from late ‘89 just as the club scene was really beginning to blow up, as well as embarking on some trips with the DiY crew. But it wasn’t the hedonistic escapism of Ibiza that steered his discursive nature, rather the one week trip to Rimini in Italy. Cocorico was the main watering hole for the summer time ravers, a dancefloor encased in a glass pyramid. “It was meant to be the new Ibiza and we went on this boat party and that’s when I shot the ‘scuse me [while] I kiss the sky image”. He went on to talk about the labels and artists from the UK that he came out with for this one week of carnage – “Weatherall, Rocky & Diesel, Terry Farley, Boys Own, Flying Records. . . all those lot took over the clubs for one week”. Terry Farley commented on one of Tony’s images – “I don’t even remember a boat party” – perfectly summarising why his images are so valuable. Other Italian excursions included the ‘House Train’, a story sent to Tony by the Guardian, who set up a train that travelled from Genoa to club Cocorico in Rimini via Turin, Milan and Bologna after two people died in a car accident, causing trade unions to take action. The result was a sea of young ravers dancing to soulful house in every carriage.

Flying Records boat party, Rimini, 1991

‘‘Scuse me whilst I kiss the sky’ – Flying Records boat party, Rimini, 1991

From left to right: Glen Gunner, Andrew Weatherall, Terry Farley, Fabi Parras Disco Pui, Italy, 1991

Tony’s career as a photographer in Nottingham veered off slightly as he moved down to London in ‘96, just after his daughter was born. He went on to snap until around 2000 where digital was becoming more popular and everyone was beginning to capture everything on mobile phones. This was a factor deterring Tony from continuing in the industry, as the format had become instantaneous, losing its charm as a successor to film photography.

He spoke of once shooting a three page spread for a magazine that was shot entirely on a five metre roll of film: a process powered by the moment and bound by undiscovered minds, contrary to the pristinely staged and consciously negotiated nature of digital shoots. The hours taken to sort and edit digital files was enough for Tony to understand that the use of the film camera was vital to capture the moment, stuck in its own time warp: the “survivors” as he calls them. Now they have resurfaced, in what he would describe as a twenty to thirty year look back at the old youth cultures, similar to the 90s nostalgia of the 70s punk scene. “There was a real romance about it . . . looking back at the past . . . but it’s very easy for our generation to say it adds more freedom . . . it’s difficult to compare as it was a different kind of energy back then”.

But it wasn’t the rave scene that Tony was actively immersed in. The fuel behind his ability to capture the wide eyed teens came from his many rollovers at Wigan casino and the Northern Soul nights. “I was a casino boy you see, I made trips up to Wigan and other all-nighters around the country most weekends and went to all the Northern Soul nights. That was my thing . . . I’m from the Wigan Casino generation”. But Wigan Casino was just one half of his youth; the punk culture is what really gravitated him towards the rave scene, fully immersed in the counter cultural energy, political referencing and integral rebellion.

The combination of two worlds colliding ignited the sensory spirit that is hard to find in today’s youth. His ability to take a step back from the rave scene was defined by his submergence in his own youth cultures. “I don’t regret not photographing my own youth”, it allowed me to stay level headed in the rave scene, for me then it was more about seeking and searching for the right moment. And with that, you capture that moment, but you’ve got no idea what it will mean in years to come”.

Datura DiY rave at Marcus Garvey Centre, 1991

Eclipse, Coventry, 1991

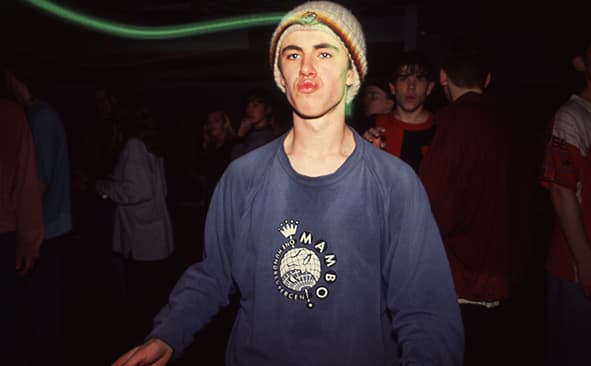

Whilst Tony found the developing world of photography into the digital age somewhat disingenuous and disengaging, he’s by no means adverse to it. Allying with the contemporary world of social media has allowed Tony to connect on a deeper level with his images by enticing a growing following of fans reliving memories of the early rave scene. In some cases, friends from afar have identified themselves and their pals in his images, transforming lost memories into connections, something that has become a solid sentiment for Tony’s achievements. “I truly love the memories it brings back for everyone but I truly love when folk some 30 years on find themselves in my old pics”. This was a response to a comment on Instagram, when spcamera was identified by his mate jayfenwick in a shot at the legendary club night Eclipse in Coventry, which depicts a teen partying with a green density streak undulating through the centre of his head which looks like an otherworldly force has taken control.

‘Raver in Mambo shirt’ – Eclipse, Coventry, 1991

I questioned why Tony’s images were not featured at last year’s Sweet Harmony exhibition at Saatchi Gallery, which celebrated 20 years since the Second Summer of Love, including photographer works from the likes of Ewen Spencer, Seana Gavin and Vinca Peterson. “They had been sleeping for a long time”, he added, much to the curator’s dismay who discovered them on his Instagram after the exhibition. Tony almost sold his negatives and camera’s as a one thousand pound job-lot before realising how valuable they could be. “But when I say valuable I don’t mean in a monetary sense ‘cos I don’t agree with putting a value like that on them. It’s for keeping the memories alive”. I asked him if he’d consider putting on an exhibition. “I’d really like to, there’s just a lot of things involved to make it all work. If I did, I’d like it to be hosted in Nottingham, back where it all began. . .”.

’What goes up must come down’ – House Train, Italy 1991

~~~

Tony Davis is a photographer from Nottingham. You can find his latest project with the British Cultural Archive where six of his images are available as prints. His full archive is available on Instagram @tonydavisphoto.

Listen to the fifth episode of Biodegradable Soundsystem here:

Author

Eleanor Bickers is an electronic music enthusiast and writer based in London. She runs the Biodegradable Soundsystem series on Threads Radio, exploring the symbiosis of written, verbal, and sonic communication. In her spare time she often finds herself DJing, raving, and imagining alternate realities. You can find her on Instagram: @lnr_dj

Back to home.